13 Reasons To Boycott Gold for Yanomami

Hunger for Gold in the Global North is fueling a living hell in the Global South. Here are 13 reasons to #BoycottGold4Yanomami. Take action every time you shop! Say no to gold and #BoycottGold!

Hunger for #gold in the Global North is fueling a living hell for #Indigenous people in the Global South. Here’s reasons why you should #BoycottGold4Yanomami #Yanomami #SayNoToGold @barbaranavarro 🥇🧐🔥☠️🚫@palmoildetect https://palmoildetectives.com/2021/12/07/here-are-13-reasons-why-you-should-boycottgold4yanomami/

Share to BlueSkyShare to TwitterBehind the insatiable appetite for #gold is a dark secret of money laundering, illegal #mining, environmental #ecocide and human misery. Make sure you #BoycottGold4Yanomami when you shop! 🥇☠️🔥🚜🧐❌#Boycott4Wildlife @BarbaraNavarro @palmoildetect https://palmoildetectives.com/2021/12/07/here-are-13-reasons-why-you-should-boycottgold4yanomami/

Share to BlueSkyShare to Twitter1. Gold mining = greenwashing of crime and corruption

2. Even the world’s biggest gold-importing nations don’t properly monitor the origins of their gold

3. Laundering crimes using gold is easy

4. Gold is a legal version of cocaine

5. Gold mining causes massive deforestation

6. Indigenous people have no rights

7. Brazil’s racist President, Bolsonaro allows land-grabbing to continue

8. Indigenous women and children are forced into sex slavery

9. Violence and murder in gold mining is common

10. Mercury kills ecosystems, people and animals

11. Ecosystems rarely recover from the damage – they are dead

12. Jewellery and electronics companies and criminals are the only ones who benefit from gold

13. Over a million children are forced to work in gold mines

How can I help?

1. Gold mining = greenwashing of crime and corruption

Image: Shutterstock

Just like in every other extractive industry in the developing world, palm oil, fossil fuels, gold mining goes hand-in-hand with greenwashing

https://twitter.com/Dragofix/status/1442168669891670017?s=20

https://twitter.com/BarbaraNavarro/status/1465648549371289602?s=20

https://twitter.com/GOLDCOUNCIL/status/1465719200333373448?s=20

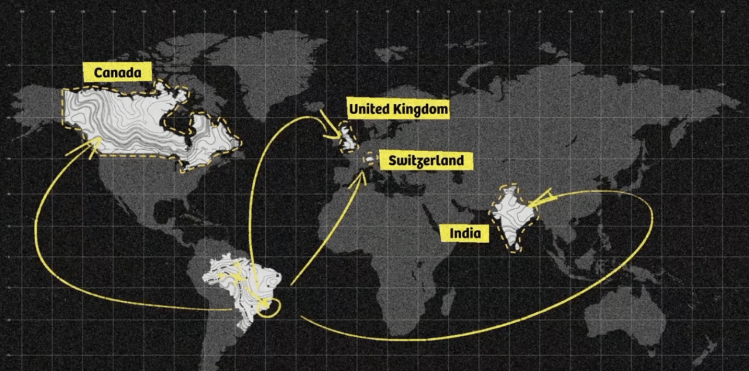

2. Even the world’s biggest gold-importing nations don’t properly monitor the origins of their gold

Image: ‘llegal gold that undermines forests and lives in the Amazon’ by Igarapé Institute

Switzerland, one of the world’s biggest gold-buying nations has weak and pathetic policies for monitoring the origin of gold

The message is loud and clear: the current system to prevent the importation and refining in Switzerland of illegal gold has been found lacking. The country’s financial watchdog reports that Customs data is not sufficiently transparent to differentiate between mined gold, bank gold and recycled gold, all of which are imported under the same code (HS 710812). This absence of identification means bars of dubious origin can easily slip through the net. The report also pinpoints inadequate legislation, compounded by underwhelming penalties: at worst, a CHF 2,000 fine.

‘Switzerland bottom of the class for gold due diligence’, Christophe Roulet, FHH Journal

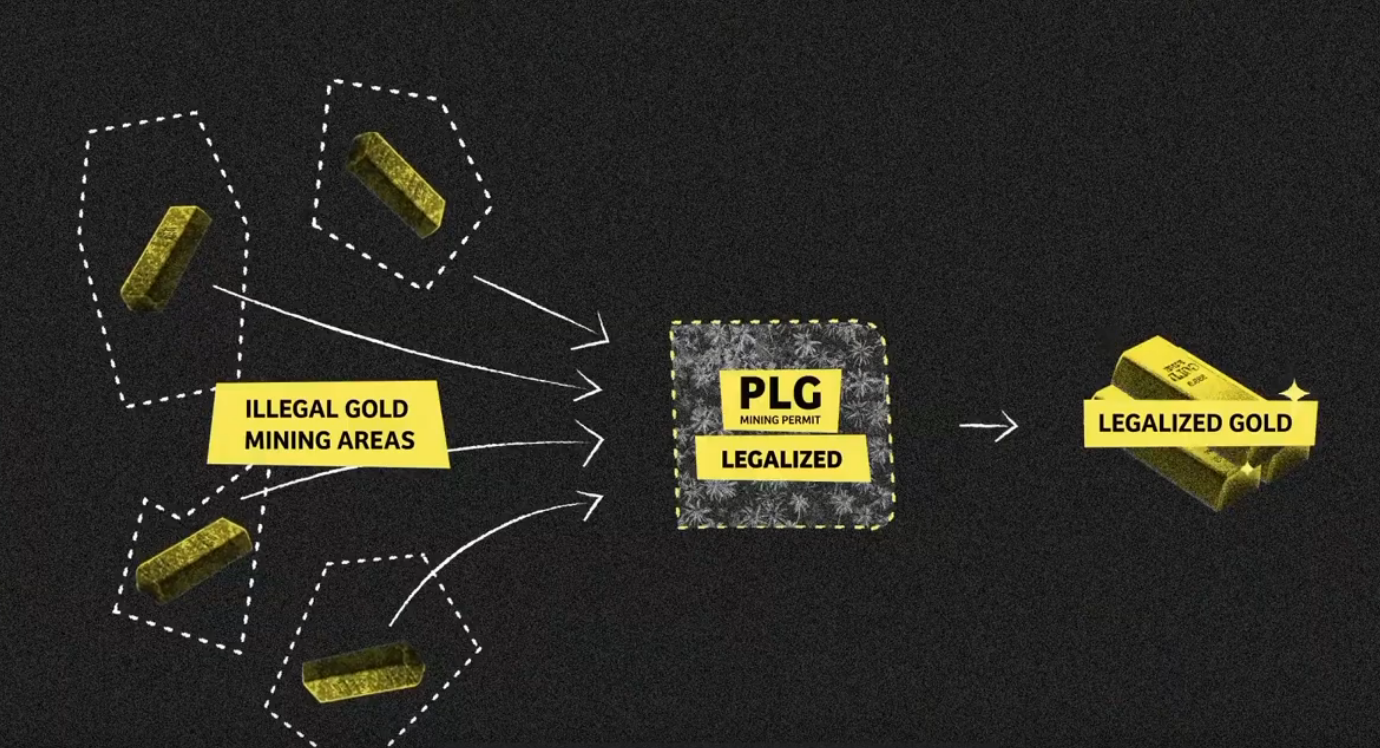

3. Laundering crimes using gold is easy

Image: ‘llegal gold that undermines forests and lives in the Amazon’ by Igarapé Institute

Corruption and laundering gold is simple and easy

Since there is no way to measure whether any given land could feasibly produce the reported amount of gold, illegal miners can co-opt owners of illegal permits to ‘wash’ gold for a fee – estimated by the public prosecutor’s office at 10% of the value of the gold transaction

In 2020, banks flagged $514.9bn suspicious transactions involving gold companies.

FinCEN Files investigations into the gold trade from around the world. Kyra Guerny, International Consortium of Investigative Journalists, 2020.

If there’s a crackdown in Peru, you just smuggle the gold across the border to Chile. Or if there’s a crackdown all across Latin America, then you can simply sell your gold through the Emirates, where there are very few controls. It’s a very difficult industry to completely eliminate the opportunities for money laundering, because it’s so global and you can just keep shifting your business.

‘‘Dirty Gold’ chases ‘three amigos’ from Miami to Peru and beyond’:

International Consortium of Investigative Journalists

Image: ‘llegal gold that undermines forests and lives in the Amazon’ by Igarapé Institute

4. Gold is a legal version of cocaine

Image: ‘llegal gold that undermines forests and lives in the Amazon’ by Igarapé Institute

For drug cartels in South America: Gold is just like a legitimate, legal version of cocaine

“Criminal groups make so much more money from gold than from cocaine, and it’s so much easier

Ivan Díaz Corzo, a former member of Colombia’s anti-criminal-mining task force. ‘How drug lords make billions smuggling gold to Miami for your jewelry and phones‘. Miami Herald, 2018.

Drug-cartel associates posing as precious-metals traders buy and mine gold in Latin America. Cocaine profits are their seed money. They sell the metal through front companies — hiding its criminal taint — to refineries in the United States and other major gold-buying nations like Switzerland and the United Arab Emirates.

Once the deal is made, the cocaine kingpins have successfully turned their dirty gold into clean cash. To the outside world, they’re not drug dealers anymore; they’re gold traders. That’s money laundering.

‘How drug lords make billions smuggling gold to Miami for your jewelry and phones‘. Miami Herald, 2018.

5. Gold mining causes massive deforestation

Mining in Indigenous territories of the Amazon is responsible for 23% of deforestation, up from 4% in 2017

“Over the past decade, illegal mining incursions — mostly small-scale gold extraction operations — have increased fivefold on Indigenous lands and threefold in other protected areas of Brazil”

‘Illegal mining in the Amazon hits record high amid Indigenous protests’, Jeff Tollerson, Nature 2021.

“The Amazon Rainforest does not burn by itself. Behind every fire that is lit is corporate greed, like agribusiness. And behind them are the largest banks and corporations in the world. They are the ones who profit from this destruction. They profit from every centimeter of land invaded, from every tree cut and burned. In the flames, they see money.”

Sônia Guajajara, executive director of the Association of Brazil’s Indigenous Peoples (APIB).

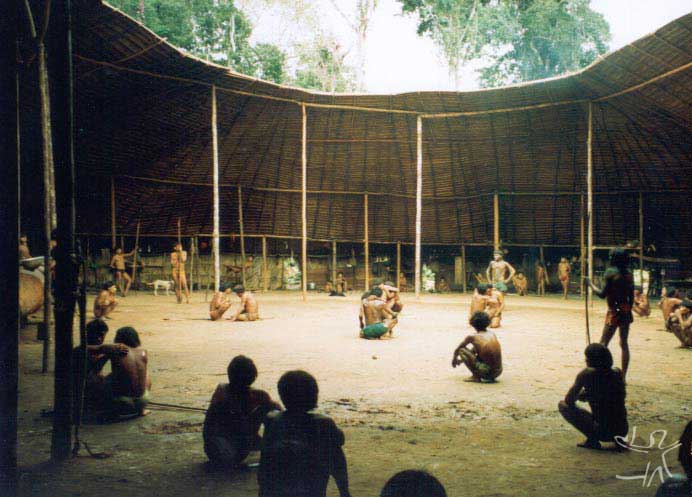

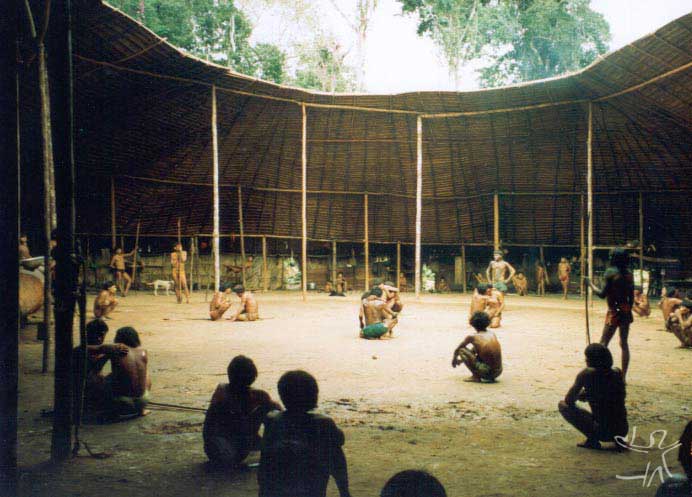

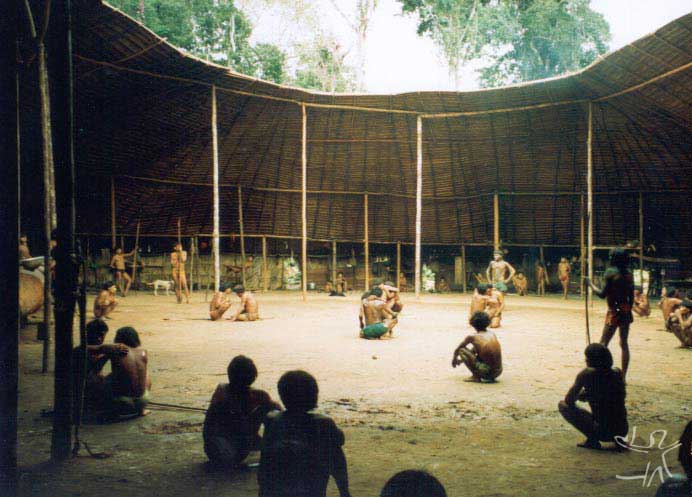

6. Indigenous Yanomami have no rights to their land

Image: ‘llegal gold that undermines forests and lives in the Amazon’ by Igarapé Institute

Venezuela’s illegitimate Maduro regime has rolled back Indigenous rights to stop Yanomami from protesting against gold mining

Venezuela’s constitution recognises its indigenous populations, yet their rights are trampled by the illegitimate Maduro criminal regime. The land is also occupied by armed Colombian groups and others working for the Maduro regime, which seeks to profit from selling the illegally mined minerals.

‘Under Maduro regime, indigenous people suffer’, Noelani Kirschner, Share America, 2020.

7. Brazil’s racist President, Bolsonaro allows land-grabbing from indigenous people

Image: Transparency International

Far Right president Jair Bolsonaro’s racist policies in Brazil call for an increase in gold mining, palm oil and cattle grazing and the ‘integration’ of Indigenous people

More than 15% of the national territory is demarcated as indigenous land and quilombolas. Less than a million people live in these truly isolated places in Brazil, exploited and manipulated by NGOs. Let’s together integrate these citizens and value all Brazilians.

Jair Bolsonaro

https://twitter.com/jairbolsonaro/status/1080468589298229253?s=20

“We are experiencing an emergency to defend indigenous lives and our territories. We need the world to know this, and to do its part. Indigenous land: not an inch less. Indigenous blood: not a single drop more.”

Sônia Guajajara, executive director of the Association of Brazil’s Indigenous Peoples (APIB).

8. Indigenous women and children are forced into sex slavery

Sex trafficking is common by women and children, as indigenous people’s traditional means of survival on the land is taken from them

The scale of sex trafficking and paedophilia around illegal gold mines in parts of Latin America is staggering. Thousands of people working there fall prey to labor exploitation by organised crime groups, simply because they have to survive. Girls as young as 12 working in the brothels and bars around illegal gold mines.

‘Sex trafficking ‘staggering’ in illegal Latin American gold mines: researchers’ By Anastasia Moloney, Thomson Reuters Foundation, 2016.

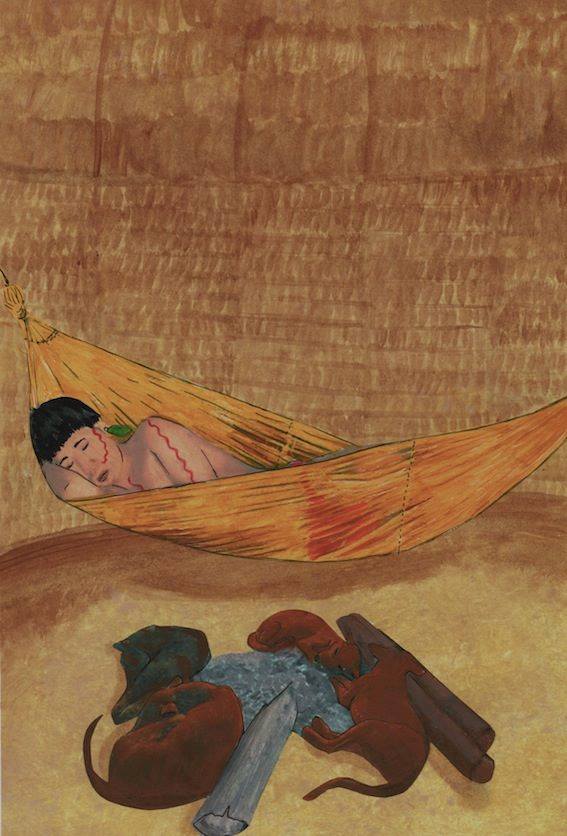

Image: Barbara Crane Navarro

Image: Barbara Crane NavarroMining regions in the rainforest have become epicenters of human trafficking, disease and environmental destruction, according to government officials and human rights investigators. Miners are forced into slavery. Prostitutes set up camps near the miners, fueling the spread of sexually transmitted infections. One human rights group found that 2,000 sex workers, 60 percent of them children, were employed in a single mining area in Peru. Meanwhile, strip mining and the indiscriminate use of mercury to ferret out gold are turning swaths of the world’s most biodiverse ecosystems into a nightmarish moonscape. In 2016, Peru declared a temporary state of emergency over widespread mercury poisoning in Madre de Dios, a jungle province rife with illegal mining. Nearly four in five adults in the area’s capital city tested positive for dangerous levels of mercury…”

9. Violence and murder in gold mining is common

Gold miners are controlled by fear of having their fingers cut off or of being executed

The illegitimate Maduro regime both controls the illegal gold mining and turns a blind eye to environmental and human rights abuses. Human Rights Watch report collected testimonials from Venezuelan gold miners. The report revealed that miners are kept under tight control by syndicates of armed criminals, such as the guerilla organisation FARC, also known as the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia, and the ELN, also known as the National Liberation Army. If miners or other members of the public are caught stealing they have their fingers publicly cut off or are killed.

‘Venezuela: Violent Abuses in Illegal Gold Mines’, Human Rights Watch, 2020.

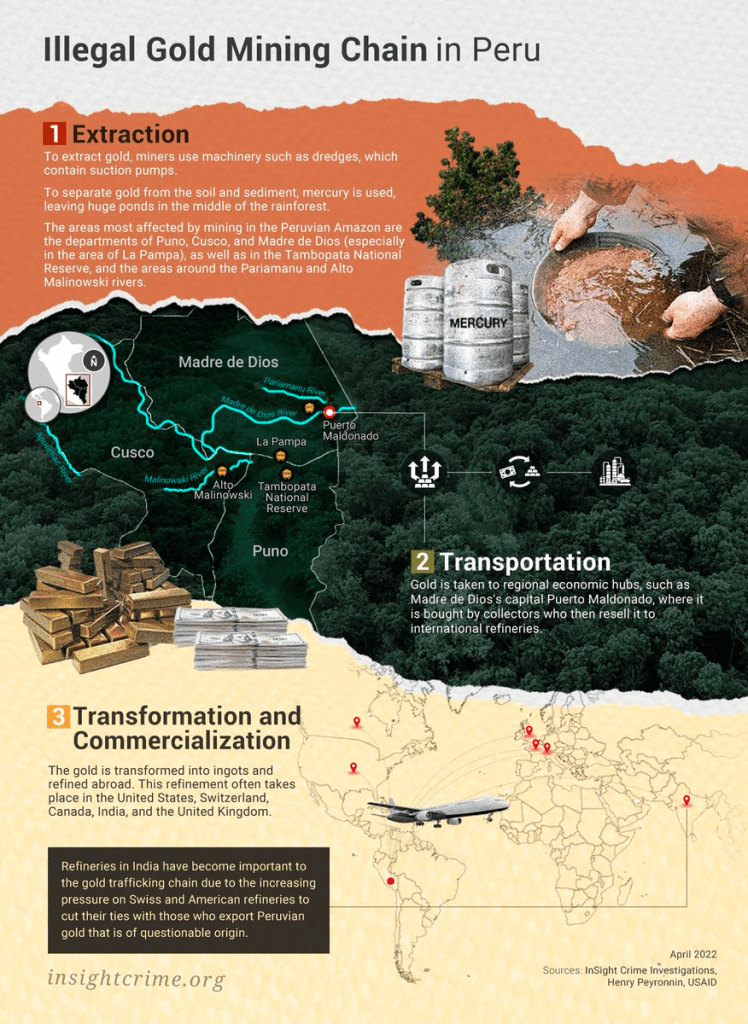

10. Mercury used in gold mining kills ecosystems, people and animals

Deadly mercury is used to extract gold out of the sludge. This poisons and kills everything in its path

Firstly, water cannons blast away river banks. After this, toxic mercury is used by miners to extract gold from the sediment. After the process, the dumping of mercury contaminates the soil and seeps into the air and water. This permanently destroys the water table, dispersing mercury 100’s of miles away, contaminating fishing stocks, animals and humans. Both people and animals in gold mining regions have high levels of mercury present in their bodies, leading to chronic illnesses and problems with brain function.

Infographic: Illegal Gold Mining Chain Peru by Insight Crime

11. Ecosystems rarely recover from the damage – they are dead

“Gold mining significantly limits the regrowth of Amazonian forests, and greatly reduces their ability to accumulate carbon. Recovery rates on abandoned mining pits and tailing ponds were among the lowest ever recorded for tropical forests, compared to recovery from agriculture and pasture.”

‘Gold mining leaves deforested Amazon land barren for years, find scientists’ The Conversation, July 1, 2020.

A typical mining site. Even five years after the mine has closed, there is still barely any vegetation. Michelle Kalamandeen, Author provided

A typical mining site. Even five years after the mine has closed, there is still barely any vegetation. Michelle Kalamandeen, Author provided

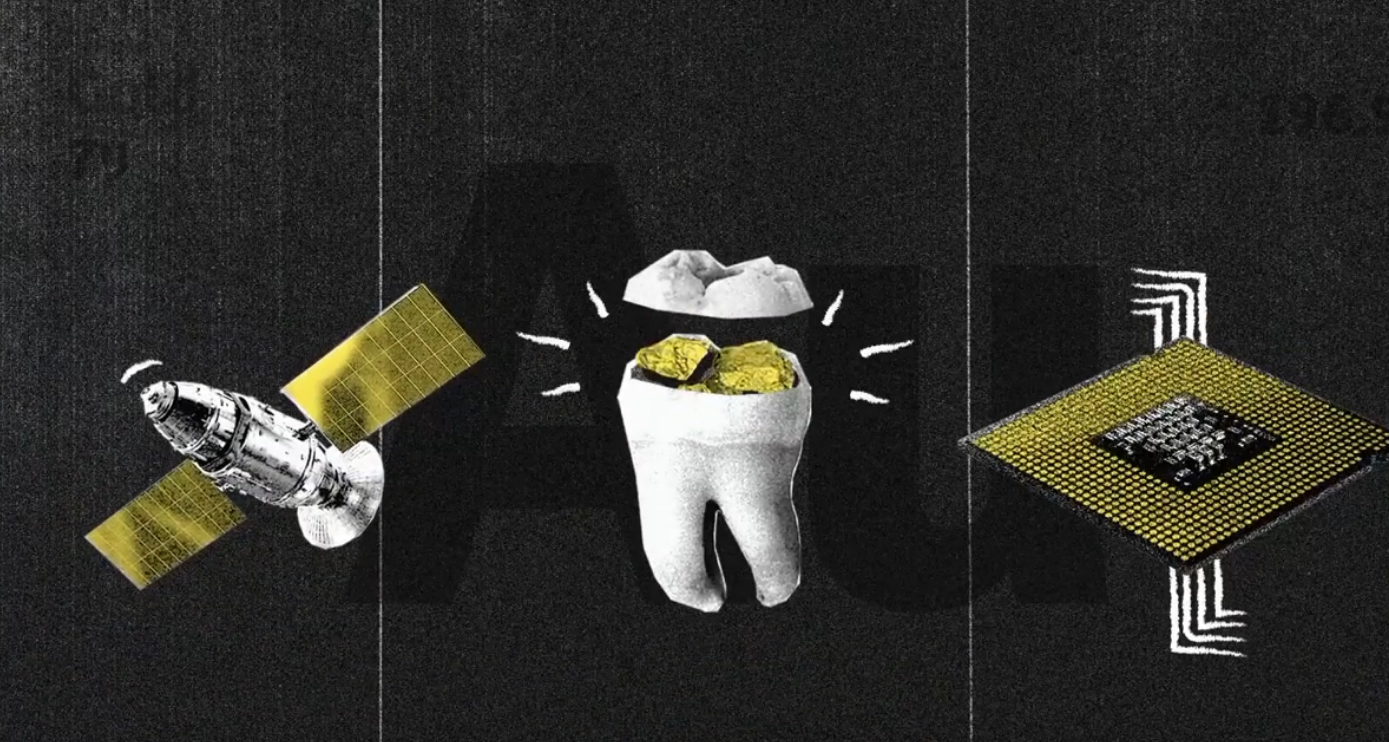

12. Jewellery and electronics companies and criminals are the only ones who benefit from gold

Image: ‘lllegal gold that undermines forests and lives in the Amazon’ by Igarapé Institute

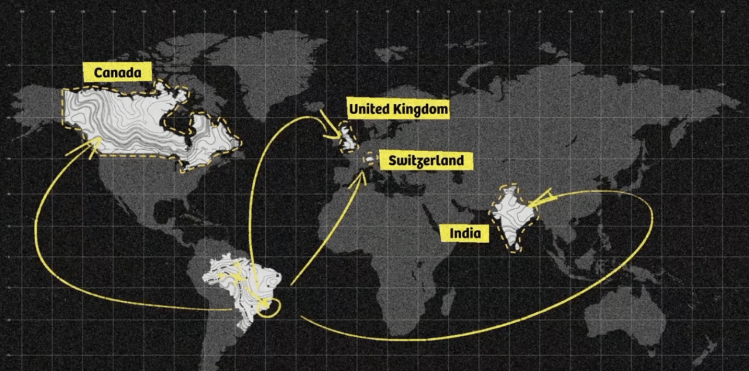

Venezuelan gold from Yanomami territories is laundered and ends up in global brands of jewellery and electronics

An investigation of mercury trafficking networks in the Amazon reveals how Venezuelan gold is laundered into legitimate supply chains and could end up in products made by the world’s biggest corporations.

Image: ‘lllegal gold that undermines forests and lives in the Amazon’ by Igarapé Institute

The tainted gold leaves the refineries in glittering bars stamped with their logos, and is sold to international corporations that incorporate the precious metal in our phones, computers, cars, and other technologies.

Mercury: Chasing the Quicksilver by InfoAmazonia

13. More than a million children work in gold mining around the world

Image: Survival

There are more than 1 million children working in goldmines around the world. Some of this gold ends up in our mobile telephones. This is the conclusion of the study conducted by SOMO Centre for Research in recent months, which was commissioned by Stop Child Labour.

Every year, the electronics industry uses 279,000 kg of gold with a value of more than 10 billion euros. Making it the third largest buyer of gold after the jewellery industry and the financial sector. Even though nearly all electronics companies state that they do not accept child labour, they are almost doing nothing to actively eradicate child labour in goldmines.

How can I help?

Image: ‘lllegal gold that undermines forests and lives in the Amazon’ by Igarapé Institute

Here’s some actions you can take every day to stop the corruption, destruction and human rights abuses associated with gold mining.

1. Raise your voice online for the Yanomami using the hashtag #BoycottGold4Yanomami

Share this article along with many articles by Indigenous Activist Barbara Crane Navarro about this issue on social media using the hashtag #BoycottGold4Yanomami

Image: Barbara Crane Navarro

2. Stop buying gold jewellery and investing in gold

Put your money where your mouth is and don’t support this corrupt and evil industry.

3. Buy vintage second-hand gold jewellery – don’t buy new gold

This makes a unique and special gift for the one you love. It also does not require more mining to get the gold jewellery. This is the ONLY form of sustainable gold jewellery.

Image: ‘lllegal gold that undermines forests and lives in the Amazon’ by Igarapé Institute

4. Don’t fall for the luxury advertising of jewellery brands like Chopard, Tiffany&Co, Cartier, Bvlgari etc.

Don’t be a sucker for luxury. Remember the reality of what gold and diamond mining is doing to the natural world and to Indigenous people.

Image: ‘lllegal gold that undermines forests and lives in the Amazon’ by Igarapé Institute

5. Fix and repair old mobile phones and laptops rather than buying new ones containing gold

This can be hard with the planned obsolescence of a lot of technology (in other words the short lifespan). However all we can do is do our best. Also you can pressure tech brands to make their goods more long-lasting and repairable and cite this as a critical reason why their industry is corrupt, greedy and needs to change.

Image: ‘lllegal gold that undermines forests and lives in the Amazon’ by Igarapé Institute

6. Support Indigenous Rights NGOs that actually stop landgrabbing in the Amazon, Africa and elsewhere like Articulation of Indigenous Peoples of Brazil (APIB)

APIB recently successfully took the Brazilian government and Bolsonaro to court for ecocide and deforestation. Avoid supporting NGO’s that do very little other than virtue-signalling, like Survival.

Support APIB

Support APIB6. Follow Barbara Crane Navarro on Twitter and WordPress

She has spent decades fighting for the Yanomami people.

Images: Barbara Crane Navarro

#Artivism #BarbaraCraneNavarro #BoycottGold #BoycottGold4Yanomami #brandBoycotts #Brazil #collectiveAction #corruption #deforestation #ecocide #extinction #gold #goldMining #indigenous #IndigenousActivism #indigenousRights #mines #mining #SayNoToGold #Venezuela #Yanomami

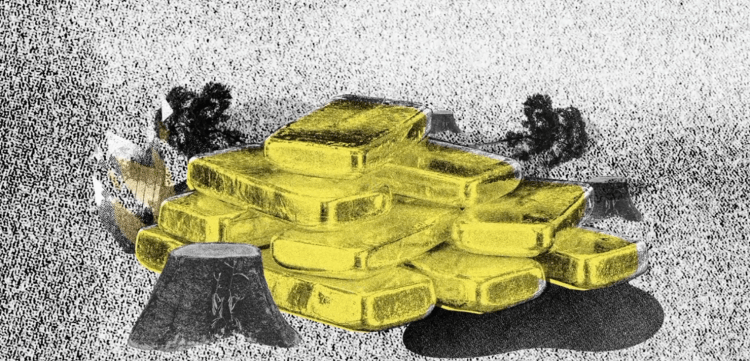

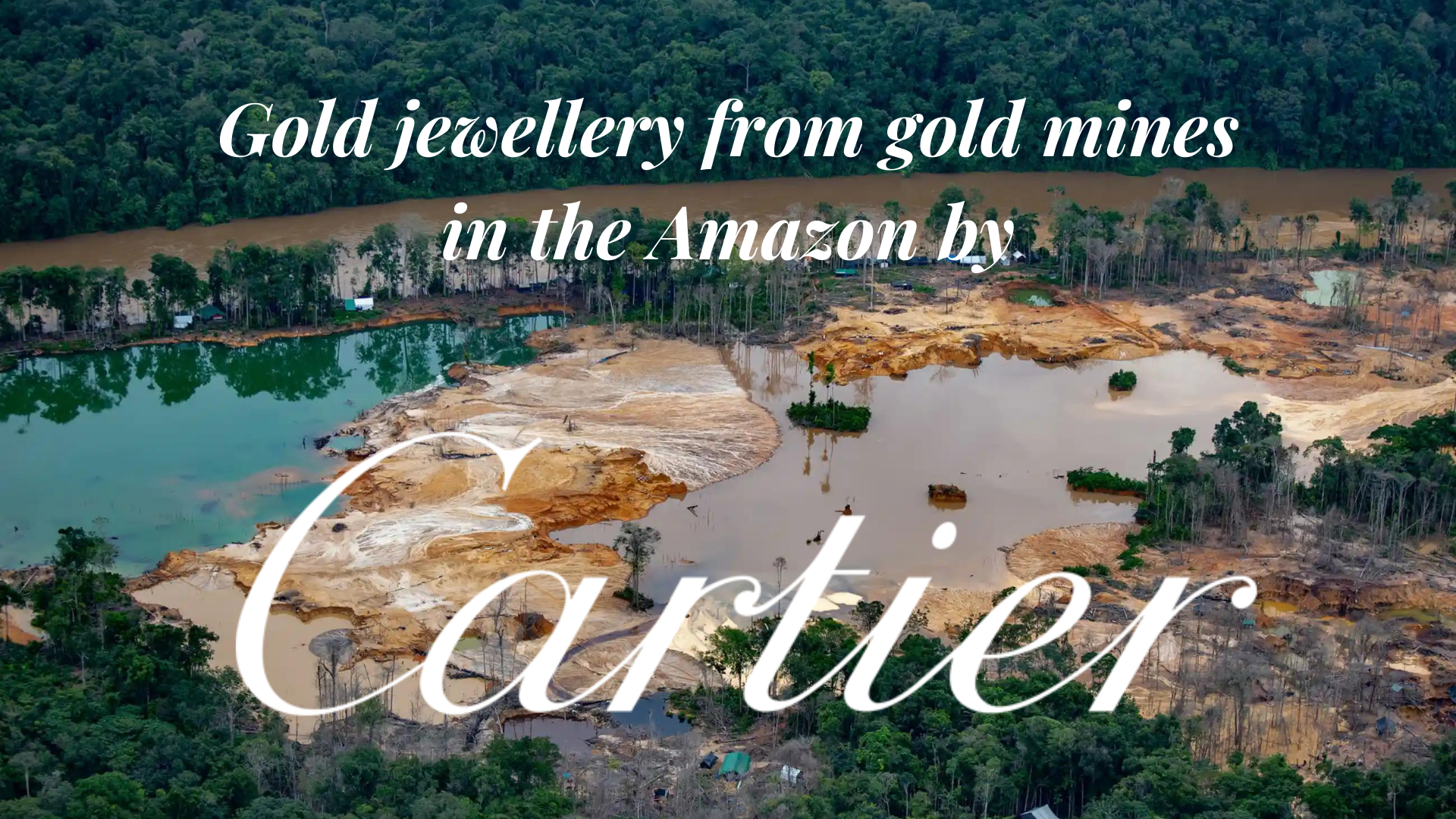

How We End Gold Mining’s Ecocide For Good

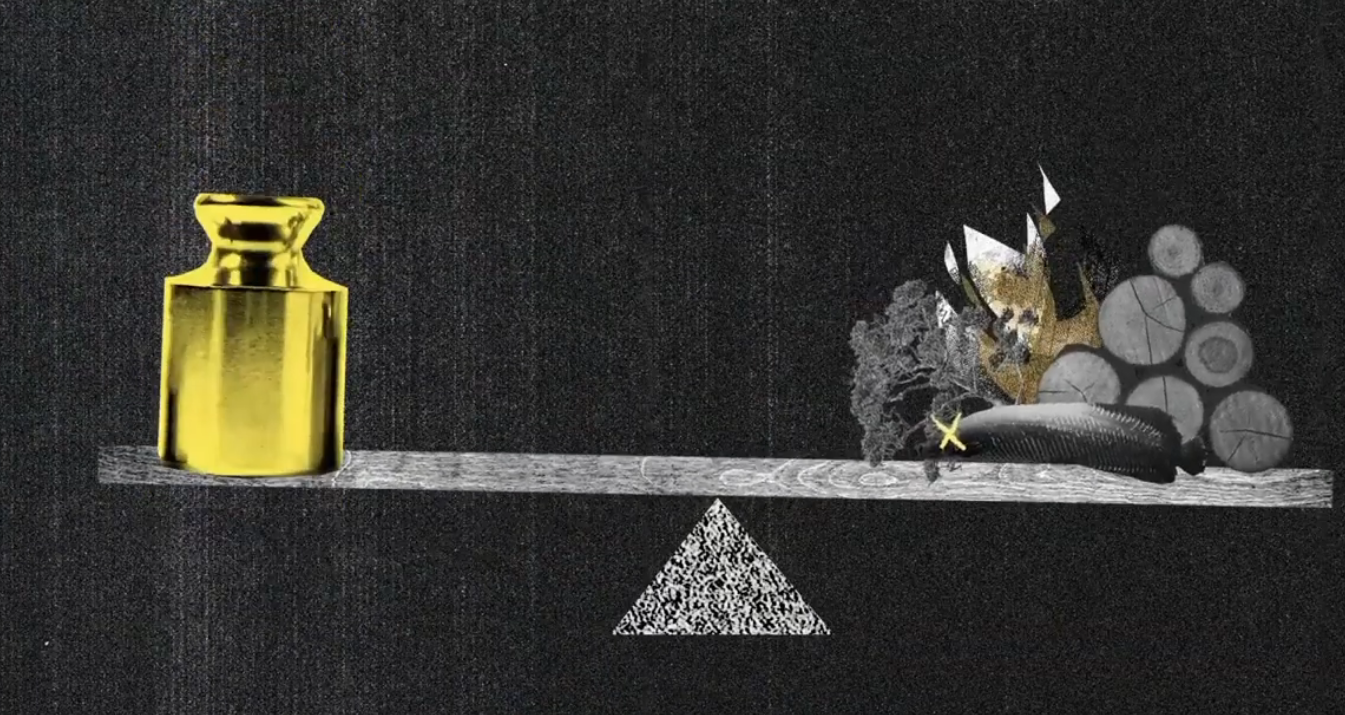

Gold mining is unparalleled in its environmental destruction and human rights toll. Frustratingly, 93% of gold is used for non-essential purposes like jewellery and investments.

A recent study suggests that transitioning to a fully circular gold economy, relying entirely on recycled gold, is achievable. Recycling gold eliminates mercury use, reduces carbon and water footprints, and still supports industries like technology and jewellery. Human rights groups have long called for the end of this destructive industry. To end gold mining, investors should focus on existing reserves. Governments must ensure justice and ‘land back’ for displaced indigenous peoples; along with a just transition for miners. Make sure you #BoycottGold #BoycottGold4Yanomami and demand the end to gold mining right now!

New #study finds that recycling #gold would eliminate the mercury pollution and #deforestation of #goldmining. It would also mean an end to violent #indigenous landgrabbing for #gold in #SouthAmerica #BoycottGold4Yanomami @BarbaraNavarro @palmoildetect https://wp.me/pcFhgU-90d

Share to BlueSkyShare to Twitter#Gold 🥇🚫 is a controversial commodity because it is unmatched in destruction to #indigenous peoples and #forests. A new study shows how we can end the #ecocide of gold #mining for good! #BoycottGold #BoycottGold4Yanomami @BarbaraNavarro @palmoildetect https://wp.me/pcFhgU-90d

Share to BlueSkyShare to Twitterhttps://youtu.be/RLsqyADpgn0?si=0as7dS8JN6v2mWr3

Written by Stephen Lezak, Research Manager at the Smith School of Enterprise and the Environment, University of Oxford. This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Two trucks transport gold ore from Barrick Cowal Gold Mine in New South Wales, Australia. Jason Benz Bennee/Shutterstock

Two trucks transport gold ore from Barrick Cowal Gold Mine in New South Wales, Australia. Jason Benz Bennee/Shutterstock

The 16th-century King Ferdinand of Spain sent his subjects abroad with the command: “Get gold, humanely if possible, but at all hazards, get gold.” His statement rings true today. Gold remains one of the world’s most expensive substances, but mining it is one of the most environmentally and socially destructive processes on the planet.

Around 7% of the gold purchased globally each year is used for industry, technology or medicine. The rest winds up in bank vaults and jewellery shops.

Beautiful objects and stable investments are worthwhile things to create and own, and often have significant cultural value. But neither can justify gold mining’s staggering human and ecological toll. In a recent study, my colleagues and I showed how it might be possible to end mining and instead rely entirely on recycled gold.

Despite improvements in gold mining practices over the past century and new regulations designed to limit mining’s impacts, this industry continues to wreak havoc upon landscapes across every continent except Antarctica.

In a given year, gold mines emit more greenhouse gases than all passenger flights between European nations combined. Gold mining also accounts for 38% of annual global mercury emissions, which cause millions of small-scale miners to suffer from chronic mercury poisoning, which can cause debilitating illness, especially in children.

Our research involved modelling hypothetical scenarios in which gold consumption could decline to more sustainable levels. Using current recycling rates, we examined a fully circular gold economy in which the world’s entire supply of gold came from recycled sources.

Even today, nearly one-quarter of annual gold demand is supplied through recycling, making it one of the world’s most recycled materials. The recycling process uses no mercury and has less than 1% of the water and carbon footprint of mined gold.

We found that a global decline in gold mining would not necessarily derail any of gold’s three central functions in jewellery, technology or as an investment.

Towards circularity

Gold stocks and three scenarios of gold flows. Lezak et al. (2022), CC BY-NC-ND

Gold stocks and three scenarios of gold flows. Lezak et al. (2022), CC BY-NC-NDOur model showed that the gold used for industrial purposes (mainly in dentistry and smartphones) could be supplied for centuries even if all gold mining stopped tomorrow.

We also found that jewellery could still be produced with recycled gold in a fully circular gold industry. There would just be about 55% less to go around, which would still leave more than enough for essential uses.

In order to make this future a reality, investors would have to limit their trading to existing reserves, without adding newly mined gold to their coffers.

A world with a shrinking supply of gold would likely mean that consumers would pay more for the same 24-karat pure gold ring. But more likely, jewellery purchases would shift to cheaper (and more durable) alloys of gold that are already popular. And in the future, demand for gold may decline as consumers become more concerned with making sustainable choices.

The role that invested gold plays in the global economy would likely continue to function regardless of extraction. Like Renaissance art, gold is valuable precisely because it is scarce. Ending gold mining would not put an end to the buying and selling of gold for bank vaults. Instead, it would make existing stocks of gold more valuable.

Irrespective of whether the world needs gold, our research suggests that the world does not need gold mining.

Private investors and central banks may balk at this idea. The US government, for example, is the world’s single largest owner of gold, holding US$11 (9.1) billion in reserves. But transitions to sustainability are always hard-won and the gold industry is no exception.

Inspired by other transitions

Like gold, the extraction of fossil fuels is also environmentally damaging. But unlike gold, fossil fuels provide warmth and electricity to homes and businesses, power to vehicles and fertiliser to farms. Transitioning away from this resource required decades of research and investment into clean energy technologies.

By contrast, finding substitutes for gold does not require any research. Jewellery can be made more sustainable by blending gold with other metals. Investors can rely on existing gold stocks and diversify to other stable assets. And technology can continue to use recycled gold when appropriate.

Closing gold mines is the first step. But many regions have grown dependent on gold mining, and artisanal mining alone supports as many as 19 million miners and their families worldwide, mostly in developing economies.

These miners deserve a just transition that ensures they do not become collateral damage in the shift to sustainability. Governments must provide a robust safety net for former gold miners and their families. That includes offering low-cost training and reskilling to ensure that miners can find employment in more sustainable industries.

Steps toward sustainability

Responsibly drawing down gold extraction will take time. But several measures are available to begin the transition today.

On the demand side of the industry, major jewellery brands, including Pandora, have already committed to using only recycled gold by 2025. Global technology firm Apple has also recently set a goal to use exclusively recycled materials by 2030.

On the supply side, mining companies should begin retiring mines that extract only gold. Many copper mines produce gold as a byproduct, which will likely continue into the future.

Meanwhile, institutional investors should stop investing in new gold mines. That includes groups like the World Bank, which has invested US$800 (£660) million in gold mines in Africa, Asia, South America and the Pacific Islands since 2010.

Justice-minded fund managers, such as those overseeing endowments, should add gold mining firms alongside coal producers to their divestment lists. And central banks should redirect their future investments toward other stable stores of value, or at least source exclusively recycled gold.

The world is filled with difficult sustainability trade-offs. Gold mining is not one of them. Drawing down this industry stands out as a relatively easy way to reduce humanity’s footprint on a fragile planet.

Written by Stephen Lezak, Research Manager at the Smith School of Enterprise and the Environment, University of Oxford. This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

ENDS

Read more about human rights abuses and greenwashing in the gold mining industry. Make sure that you #BoycottGold4Yanomami!

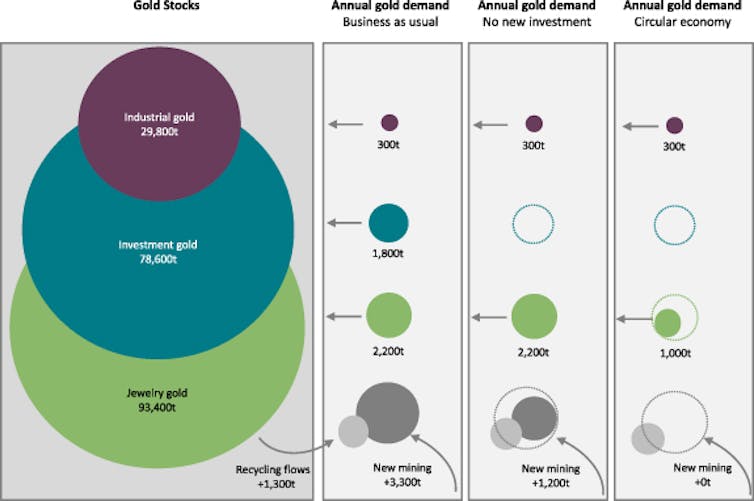

Did you know that gold kills indigenous people and rare animals?

Gold mining kills indigenous peoples throughout the world like the Yanomami people of Brazil and Papuans in West Papua. The bloody, violent and greedy landgrabbing that goes on for gold forces indigenous women…

Artist and Indigenous Rights Advocate Barbara Crane Navarro

Artist Barbara Crane Navarro merges art and activism to defend the Amazon and Yanomami from destructive gold mining. Support #BoycottGold4Yanomami.

13 Reasons To Boycott Gold for Yanomami

Hunger for Gold in the Global North is fueling a living hell in the Global South. Here are 20 reasons why you should #BoycottGold4Yanomami

Take Action in Five Ways

1. Join the #Boycott4Wildlife on social media and subscribe to stay in the loop: Share posts from this website to your own network on Twitter, Mastadon, Instagram, Facebook and Youtube using the hashtags #Boycottpalmoil #Boycott4Wildlife.

Enter your email address

Sign Up

Join 3,529 other subscribers2. Contribute stories: Academics, conservationists, scientists, indigenous rights advocates and animal rights advocates working to expose the corruption of the palm oil industry or to save animals can contribute stories to the website.

Wildlife Artist Juanchi Pérez

Mel Lumby: Dedicated Devotee to Borneo’s Living Beings

Anthropologist and Author Dr Sophie Chao

Health Physician Dr Evan Allen

The World’s Most Loved Cup: A Social, Ethical & Environmental History of Coffee by Aviary Doert

How do we stop the world’s ecosystems from going into a death spiral? A #SteadyState Economy

3. Supermarket sleuthing: Next time you’re in the supermarket, take photos of products containing palm oil. Share these to social media along with the hashtags to call out the greenwashing and ecocide of the brands who use palm oil. You can also take photos of palm oil free products and congratulate brands when they go palm oil free.

https://twitter.com/CuriousApe4/status/1526136783557529600?s=20

https://twitter.com/PhillDixon1/status/1749010345555788144?s=20

https://twitter.com/mugabe139/status/1678027567977078784?s=20

4. Take to the streets: Get in touch with Palm Oil Detectives to find out more.

5. Donate: Make a one-off or monthly donation to Palm Oil Detectives as a way of saying thank you and to help pay for ongoing running costs of the website and social media campaigns. Donate here

Pledge your support#BarbaraCraneNavarro #BoycottGold #BoycottGold4Yanomami #corruption #deforestation #ecocide #forests #gold #goldMining #goldmining #humanRights #indigenous #indigenousRights #mining #SouthAmerica #study #workersRights #WorkersRights #Yanomami

Tucuxi Sotalia fluviatilis

Tucuxi Sotalia fluviatilis

IUCN Red List Status: Endangered

Location: #Brazil, #Peru, #Colombia, #Ecuador

Found throughout the #Amazon and Solimões River systems, including major tributaries and large lakes. Their range spans lowland rainforest areas of Brazil, southeastern Colombia, eastern Ecuador, and southern Peru.

The #Tucuxi, a small freshwater #dolphin of #Peru, #Ecuador, #Colombia and #Brazil now faces a dire future. Once common throughout the Amazon River system, they are now listed as #Endangered due to accelerating population declines. Threats include drowning in fishing nets, deforestation, mercury poisoning from gold mining, #palmoil run-off, oil drilling, and dam construction. A shocking 97% decline was recorded over 23 years in a single Amazon reserve. Without urgent action, this elegant and playful river dolphin could vanish from South America’s waterways. Use your wallet as a weapon against extinction. Choose palm oil-free, and #BoycottGold #BoycottPalmOil #Boycott4Wildlife

Playful and intelligent #Tucuxi are small #dolphins 🐬 of #Amazonian rivers in #Peru 🇵🇪 #Brazil 🇧🇷 #Ecuador 🇪🇨 and #Colombia 🇨🇴. #PalmOil and #GoldMining are major threats 😿 Fight for them! #BoycottGold #BoycottPalmOil #Boycott4Wildlife @palmoildetect https://palmoildetectives.com/2025/11/23/tucuxi-sotalia-fluviatilis/

Share to BlueSky Share to TwitterClever and joyful #Tucuxi are #dolphins 🐬💙 endangered by #hunting #gold #mining and contamination of the Amazon river 🇧🇷 for #PalmOil #agriculture ☠️ Use your wallet as a weapon and #BoycottGold 🥇🚫 #BoycottPalmOil 🌴🚫 #Boycott4Wildlife @palmoildetect https://palmoildetectives.com/2025/11/23/tucuxi-sotalia-fluviatilis/

Share to BlueSky Share to TwitterAppearance & Behaviour

Tucuxis are often mistaken for their oceanic dolphin cousins due to their streamlined bodies, short beaks, and smooth, pale-to-dark grey skin. But these freshwater dolphins are wholly unique—adapted to life in winding river systems where water levels rise and fall dramatically with the seasons.

What sets them apart is their remarkable intelligence and tightly knit social groups. Tucuxis are playful and curious by nature. They leap from the water in graceful arcs, sometimes spinning mid-air.

The Tucuxi, sometimes called the ‘grey dolphin’ due to their uniform colouring, resembles a smaller oceanic dolphin, with a streamlined body and slender beak. Their colour varies from pale grey on the belly to darker grey or bluish-grey along the back.

They travel in small groups of two to six, displaying coordinated swimming patterns. In rare cases, they may form groups up to 26 individuals, particularly at river confluences. Known for their agility, they leap and spin in the water with a grace that belies their size. Tucuxis are particularly drawn to dynamic habitats like river junctions, where waters mix and fish gather.

Threats

- Widespread deforestation from palm oil plantations Palm oil plantations are rapidly expanding across the Amazon, clearing vast tracts of forest that stabilise riverbanks and filter water. This deforestation leads to increased sedimentation in rivers, altering flow patterns and reducing water clarity—conditions that directly disrupt the Tucuxi’s feeding and movement. Run-off from fertilisers and pesticides used in palm oil monocultures also poisons aquatic ecosystems, harming Tucuxis other Amazonian dolphin species and the fish they rely on.

- Toxic mercury pollution from gold mining Artisanal and illegal gold mining in the Amazon releases massive quantities of mercury into the water, contaminating fish and other aquatic organisms. Tucuxis, as top predators, ingest this mercury through their prey, which accumulates in their tissues and causes neurological damage, weakened immunity, and reproductive failure. Mercury exposure is one of the most insidious threats, as it persists in ecosystems long after mining has ceased.

- Incidental drowning in fishing nets Tucuxis are frequently caught and killed in gillnets and other fishing gear as bycatch. Tucuxis and other Amazonian dolphins often inhabit the same confluence zones and productive fishing grounds targeted by local communities, making entanglement almost inevitable. Many carcasses are never recovered, having either been discarded by fishers or lost to river currents, meaning actual mortality rates are likely far higher than reported.

- Deliberate hunting for use as fish bait Though illegal, Tucuxis continue to be targeted and killed in parts of Brazil, especially near the Mamirauá and Amana Reserves, where they are used as bait in the piracatinga (catfish) fishery. This brutal practice involves harpooning or netting dolphins and using their flesh to lure fish, often alongside the killing of Botos. Despite a national ban, weak enforcement and ongoing demand mean this threat persists in remote and lawless regions.

- Illegal fishing with explosives and toxins In certain areas, particularly in Brazil and Peru, fishers use home-made explosives and poisoned bait to stun or kill fish en masse. These destructive methods harm or kill Tucuxis who are attracted by the sudden appearance of dead or stunned prey. The concussive force of explosions and the ingestion of poisoned prey result in slow, agonising deaths for affected dolphins.

- Construction of hydroelectric dams Dams fragment Tucuxi populations by blocking their movement along river corridors, reducing access to feeding and breeding grounds. These projects alter seasonal water flow, raise water temperatures, and flood critical habitats—conditions that significantly disrupt dolphin ecology. Brazil alone has 74 operational dams in the Amazon basin, with over 400 more planned, posing a long-term existential threat to freshwater cetaceans.

- Run-off and contamination from palm oil, soy and meat agriculture In addition to habitat loss, palm oil and soy plantations along with cattle ranching generates enormous volumes of chemical-laden waste, which enters waterways and poisons aquatic life. This pollution affects Tucuxis both directly and indirectly—exposing them to harmful substances and killing off sensitive fish species. As plantations replace biodiverse forests, the ecosystem becomes less resilient, accelerating the decline of species like the Tucuxi.

- Bioaccumulation of heavy metals and industrial pollutants Tucuxis, like many river dolphins, suffer from exposure to persistent organic pollutants such as PCBs, DDT, and flame retardants, as well as heavy metals like lead and cadmium. These toxins accumulate in dolphin tissues over time, weakening their immune systems, interfering with reproduction, and making them more vulnerable to disease. Contaminants originate from industrial waste, agriculture, and mining, and are now widespread across the Amazon basin.

- Habitat fragmentation from infrastructure and oil development Roads, oil pipelines, and shipping corridors criss-cross many parts of the Tucuxi’s range, slicing through their habitat and increasing the risk of collisions with boats. These developments also bring noise pollution, which can interfere with echolocation and communication. Fragmentation leads to isolated subpopulations, reducing genetic diversity and making recovery more difficult.

Geographic Range

The Tucuxi inhabits the Amazon River basin, spanning: Brazil, Peru, Colombia, Ecuador These river dolphins occur as far west as southern Peru and eastern Ecuador, and as far north as southeastern Colombia. They are notably absent from Bolivia’s Beni/Mamoré system, the Orinoco basin, and upper reaches above major waterfalls or rapids.

Their range includes wide, deep rivers and lakes, avoiding turbulent rapids and shallow areas. Despite overlapping with the Amazon River Dolphin (Inia geoffrensis), Tucuxis do not enter flooded forest habitats and stay closer to main river channels.

Diet

Tucuxis feed on more than 28 species of small, schooling freshwater fish, including members of the characid, sciaenid, and siluriform families. During the dry season, fish are concentrated in shrinking waterways, making them easier to catch. In contrast, flooding season disperses prey into forested areas, beyond the Tucuxi’s reach. They prefer to feed at river junctions and along confluences, where nutrient-rich waters concentrate fish populations.

Mating and Reproduction

Little is known about their mating behaviours. However, individuals appear to remain within familiar ranges for many years, and females likely give birth to a single calf after a long gestation. Calves are dependent for an extended period, learning complex navigation and foraging skills in rapidly changing river systems. The estimated generation length is 15.6 years.

FAQs

How many Tucuxis are left in the wild?

There is no comprehensive global population estimate. However, surveys from 1994–2017 in Brazil’s Mamirauá Reserve show a 7.4% annual decline—amounting to a 97% drop over three generations (da Silva et al., 2020). If this trend reflects the wider Amazon basin, the species could be on the brink of collapse.

How long do Tucuxis live?

Exact lifespans are unknown, but based on reproductive data and life history modelling, their generation length is around 15.6 years (Taylor et al., 2007), suggesting natural lifespans of 30–40 years.

How are palm oil and gold mining affecting Tucuxis?

Out-of-control palm oil expansion results in massive deforestation and run-off, clogging rivers with sediment and toxic agrochemicals. Gold mining adds mercury into aquatic ecosystems, where it bioaccumulates in fish—Tucuxis’ main food source. These pollutants cause reproductive harm, neurological damage, and immune system failure in dolphins.

Do Tucuxis make good pets and should they be kept in zoos?

Absolutely not. Tucuxis are intelligent, wild animals. Keeping them in captivity is deeply cruel and has no conservation benefit. Wild capture destroys families and can devastate local populations. If you care about these dolphins, say no to the exotic pet trade and the cruel zoo trade.

What habitats do they prefer?

Research in Peru’s Pacaya-Samiria Reserve shows that Tucuxis prefer river confluences and wide channels, particularly during the dry season when fish density is higher (Belanger et al., 2022). Feeding activity is especially concentrated in areas where whitewater rivers meet blackwater tributaries, creating nutrient-rich hotspots.

Take Action!

The Tucuxi is vanishing before our eyes. To protect them:

• Boycott palm oil and gold products linked to Amazon destruction.

• Choose fish-free and vegan products to reduce pressure on river ecosystems.

• Support indigenous-led conservation across the Amazon.

• Campaign for a ban on destructive dams, and the end of illegal fishing.

#BoycottPalmOil #Boycott4Wildlife #Vegan #BoycottMeat

Support the Tucuxi by going vegan and boycotting palm oil in the supermarket, it’s the #Boycott4Wildlife

Support the conservation of this species

This animal has no protections in place. Read about other forgotten species here. Create art to support this forgotten animal or raise awareness about them by sharing this post and using the #Boycottpalmoil #Boycott4Wildlife hashtags on social media. Also you can boycott palm oil in the supermarket.

Further Information

Belanger, A., Wright, A., Gomez, C., Shutt, J.D., Chota, K., & Bodmer, R. (2022). River dolphins (Inia geoffrensis and Sotalia fluviatilis) in the Peruvian Amazon: habitat preferences and feeding behaviour. Latin American Journal of Aquatic Mammals, 17(1). https://doi.org/10.5597/lajam00268

da Silva, V., Martin, A., Fettuccia, D., Bivaqua, L. & Trujillo, F. 2020. Sotalia fluviatilis. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2020: e.T190871A50386457. https://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2020-3.RLTS.T190871A50386457.en. Accessed on 06 April 2025.

Monteiro-Neto, C., Itavo, R. V., & Moraes, L. E. S. (2003). Concentrations of heavy metals in Sotalia fluviatilis (Cetacea: Delphinidae) off the coast of Ceará, northeast Brazil. Environmental Pollution, 123(2), 319–324. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0269-7491(02)00371-8

How can I help the #Boycott4Wildlife?

Take Action in Five Ways

1. Join the #Boycott4Wildlife on social media and subscribe to stay in the loop: Share posts from this website to your own network on Twitter, Mastadon, Instagram, Facebook and Youtube using the hashtags #Boycottpalmoil #Boycott4Wildlife.

Enter your email address

Sign Up

Join 3,172 other subscribers2. Contribute stories: Academics, conservationists, scientists, indigenous rights advocates and animal rights advocates working to expose the corruption of the palm oil industry or to save animals can contribute stories to the website.

Wildlife Artist Juanchi Pérez

Mel Lumby: Dedicated Devotee to Borneo’s Living Beings

Anthropologist and Author Dr Sophie Chao

Health Physician Dr Evan Allen

The World’s Most Loved Cup: A Social, Ethical & Environmental History of Coffee by Aviary Doert

How do we stop the world’s ecosystems from going into a death spiral? A #SteadyState Economy

3. Supermarket sleuthing: Next time you’re in the supermarket, take photos of products containing palm oil. Share these to social media along with the hashtags to call out the greenwashing and ecocide of the brands who use palm oil. You can also take photos of palm oil free products and congratulate brands when they go palm oil free.

https://twitter.com/CuriousApe4/status/1526136783557529600?s=20

https://twitter.com/PhillDixon1/status/1749010345555788144?s=20

https://twitter.com/mugabe139/status/1678027567977078784?s=20

4. Take to the streets: Get in touch with Palm Oil Detectives to find out more.

5. Donate: Make a one-off or monthly donation to Palm Oil Detectives as a way of saying thank you and to help pay for ongoing running costs of the website and social media campaigns. Donate here

Pledge your supportLearn about other animals endangered by palm oil and other agriculture

GlobalSouth America S.E. AsiaIndiaAfricaWest Papua & PNG

Frill-Necked Lizard Chlamydosaurus kingii

Grey Crowned Crane Balearica regulorum

Ecuadorean Viscacha Lagidium ahuacaense

Southern Pudu Pudu puda

Blue-streaked Lory Eos reticulata

Blonde Capuchin Sapajus flavius

Learn about “sustainable” palm oil greenwashing

Read more about RSPO greenwashing

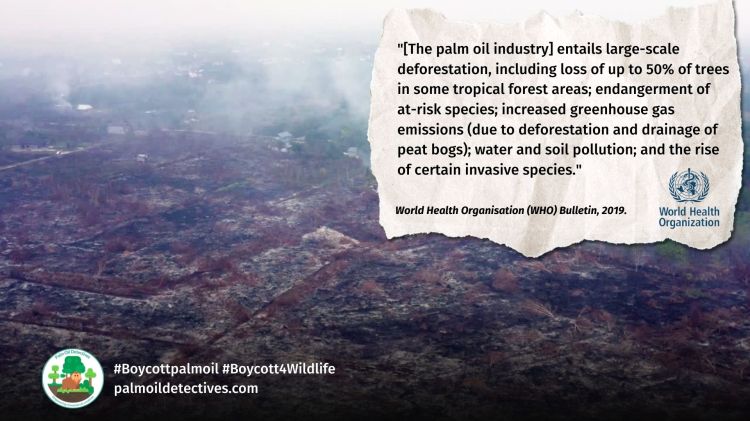

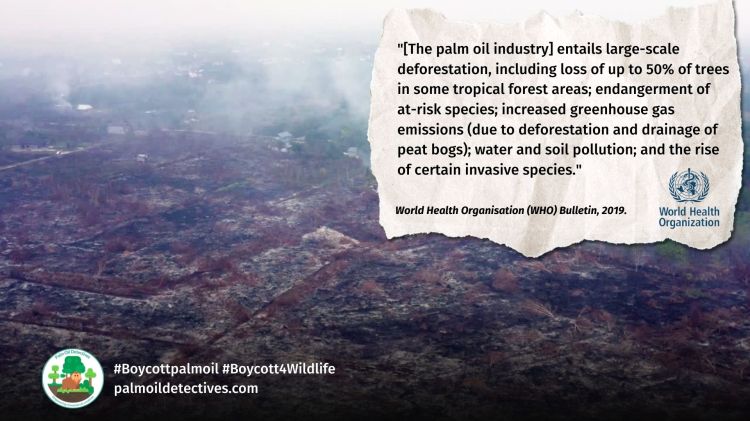

Lying Fake labelsIndigenous Land-grabbingHuman rights abusesDeforestation Human health hazardsA 2019 World Health Organisation (WHO) report into the palm oil industry and RSPO finds extensive greenwashing of palm oil deforestation and the murder of endangered animals (i.e. biodiversity loss)

Read more

#agriculture #amazon #amazonRainforest #amazonia #amazonian #animalCruelty #animals #boycott4wildlife #boycottgold #boycottmeat #boycottpalmoil #brazil #colombia #dams #deforestation #dolphin #dolphins #ecuador #endangered #endangeredSpecies #forgottenAnimals #gold #goldMining #goldmining #humanWildlifeConflict #hunting #hydroelectric #mammal #mining #palmOil #palmOilDeforestation #palmoil #peru #poaching #saynotogold #tucuxi #tucuxiSotaliaFluviatilis #vegan

Indigenous Peoples Fight Climate Change

In the wake of the worst wildfires in living memory in Mexico and Central America in 2024, news outlets were looking for someone to blame. Howler monkeys and many species of parrots perished in the blazes. Slash and burn farming practices by Belize‘s indigenous communities were singled out as a primary cause. Yet this knee-jerk reaction is not evidence based and doesn’t take into account forces like corporate landgrabbing for mining and agribusinesses like meat, soy and palm oil.

Belize’s indigenous Maya communities are rebuilding stronger based on the collective notion of se’ komonil: reciprocity, solidarity, traditional knowledge, gender equity, togetherness and community.

In the wake of horrific #wildfires in #Belize and #Mexico caused by #climatechange, #indigenous #Maya are rebuilding using the notion of se’ komonil: reciprocity #community and solidarity. #indigenousrights #landrights #BoycottPalmOil @palmoildetect https://wp.me/pcFhgU-924

Share to BlueSky Share to TwitterWritten by James Stinson, Senior Research Associate and Evaluation Specialist, Young Lives Research Lab, Faculty of Education, York University, Canada and Lee Mcloughlin, PhD student, Global Sociocultural Studies, Florida International University This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Driven by extreme heat and drought, some of the worst wildfires in living memory raged across Mexico and Central America through April and May 2024.

News agencies reported howler monkeys dropping dead from trees, and parrots and other birds falling from the skies.

In Belize, a state of emergency was declared as wildfires burned tens of thousands of hectares of highly bio-diverse forest. Farmers suffered huge losses as fires destroyed crops and homes, and communities across the country suffered from hazardous air quality and hot, sleepless nights. Many risked their lives to fight off the approaching fires.

As the wildfire crisis subsided with rains in June, public attention shifted toward identifying the causes and allocating blame. Many singled out the “slash and burn” farming practices in Belize’s Indigenous communities as the primary cause. This simple knee-jerk reaction ignores the underlying causes of the climate crisis, are scientifically unfounded and stoke resentment of Indigenous Peoples.

Young Mayan women. Image source: Wikipedia

Young Mayan women. Image source: WikipediaFanning the flames

On June 5, one of Belize’s major news networks ran a story with the headline “Are Primitive Farming Techniques Responsible for Wildfires?” The story placed blame for Belize’s wildfires on “slash-and-burn farming”, arguing that “there has to be a shift away from this destructive means of agriculture.”

The story was followed by an op-ed published online asserting that “because of the increased amounts of escaped agricultural fires, aided by climate change, global warming and drought, slash and burn has become more of a problem than the solution it once was.” This sentiment was further reinforced by Belize’s prime minister, who declared that “slash аnd burn has to be something of the past.”

While some of the recent fires in Belize were connected to agricultural burning — and poorly managed fire-clearing practices can have negative air-quality impacts — blaming “slash and burn” for the wildfire crisis ignores the larger context and conditions that made it possible, namely global warming.

May 2024 was the hottest and driest month in Belize’s history. This extreme heat is part of a broader global trend, with June 2024 marking the 13th consecutive “hottest month on record” globally.

More fundamentally, these statements confuse other forms of slash-and-burn agriculture with the distinct “milpa” systems employed by Indigenous people in Belize.

Indigenous knowledge undermined

Throughout Belize, Indigenous Maya farmers commonly practise a form of agriculture referred to as milpa in which fire is used to clear fields and fertilize the soil. Within this system, small areas of forest are chopped down, burned, and planted with maize, beans, squash and other crops. After being cultivated for a year or two, the field is then left fallow and allowed to regenerate back to forest cover while the farmers move on to a new area within a cyclical pattern where areas are reused after a regenerative period.

Commonly derided as slash-and-burn farming, milpa has long been perceived as environmentally destructive. This perspective has been perpetuated by long-standing myths and misconceptions that portray the farming practices of non-Europeans, and specifically the use of fire, as wasteful and irrational.

In Belize, this negative view of slash and burn has driven many colonial and post-colonial interventions to modernize Maya farming practices.

Recent research, however, has shown that the lands of Indigenous Peoples around the world have reduced deforestation and degradation rates relative to non-protected areas. The southern Toledo district of Belize, where the majority of Maya communities are located, boasts a forest cover rate of 71 per cent, significantly higher than the national average of 63 per cent.

Further research has found that the species composition of contemporary Mesoamerican forests has been shaped by the agricultural practices of ancient Maya farmers.

In Belize, fire has been found to play a role in promoting ecosystem health and resilience and intermediate levels of forest disturbance caused by milpa can increase species diversity. Well-managed milpa farming can support soil fertility, result in long-term carbon sequestration and enriched woodland vegetation.

Research has also shown that previous studies of deforestation in southern Belize significantly overestimated the rate of deforestation due to milpa agriculture by not accounting for its rotational process.

Many researchers now believe that milpa is a more benign alternative, in terms of environmental effects, than most other permanent farming systems in the humid tropics. Indeed, findings such as these have led to a growing appreciation for the role of Indigenous Peoples in advancing nature-based and life-enhancing climate solutions.

Unfortunately, research in the region has also found that climate change is undermining the ecological sustainability of milpa farming by forcing farmers to abandon traditional practices and adopt counterproductive measures in their struggle to adapt. In some cases, this has resulted in a decrease in the biodiversity and ecological resilience of the milpa system. This issue is compounded by the decreasing participation of young people, resulting in a further generational loss of traditional ecological knowledge.

Together, these issues are serving to alter and undermine a livelihood strategy that has proven sustainable for thousands of years. However, rather than call for Maya farmers to abandon slash and burn, we encourage support for the self-determined efforts of Maya communities to adapt to this changing climate. https://www.youtube.com/embed/ok787HRp_gA?wmode=transparent&start=0 A video documenting the Maya response to the 2024 wildfire crisis.

Planting seeds of collaboration

Since winning a groundbreaking land rights claim in 2015, Maya communities in southern Belize have been working to promote an Indigenous future based on principles of reciprocity, solidarity, traditional knowledge, gender equity and, most significantly, se’ komonil, the Maya notion of togetherness and community.

Led by a collaboration of Maya leaders and non-governmental organizations, work toward this has included efforts to revitalize traditional institutions and governance systems, as well as the development of an Indigenous Forest Caring Strategy and fire-permitting system. In an effort to encourage and support the participation of youth in this process, Maya leaders have collaborated with the Young Lives Research Lab at York University to develop the Partnership for Youth and Planetary Wellbeing.

Building on previous research with Maya youth, the project has produced innovative youth-led research and education on the impacts of climate change, the importance of food sovereignty, traditional ecological knowledge and the struggle to secure Indigenous land rights in Maya communities. This work has been shared with global policymakers at the United Nations and local audiences in Belize.

Rather than fanning the flames of climate blame, we must work together to revitalize Indigenous knowledge systems and plant seeds of climate collaboration and care.

Written by James Stinson, Senior Research Associate and Evaluation Specialist, Young Lives Research Lab, Faculty of Education, York University, Canada and Lee Mcloughlin, PhD student, Global Sociocultural Studies, Florida International University This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

ENDS

Read more about human rights abuses and child slavery in the palm oil and gold mining industries

SOCFIN’s African Empire of Colonial Oppression: Billionaires Profit from Palm Oil and Rubber Exploitation

Investigation by Bloomberg exposes that despite being RSPO members, #SOCFIN plantations in #WestAfrica are the epicentre of #humanrights abuses, sexual coercion, environmental destruction, and #landgrabbing. Operating in #Liberia, #Ghana, #Nigeria, and beyond, SOCFIN’s…

Palm Oil Threatens Ancient Noken Weaving in West Papua

Colonial palm oil and sugarcane causing the loss of West Papuans’ cultural identity. Land grabs force communities from forests, threatening Noken weaving

Family Ties Expose Deforestation and Rights Violations in Indonesian Palm Oil

An explosive report by the Environment Investigation Agency (EIA) details how Indonesia’s Fangiono family, through a wide corporate web, is linked to ongoing #deforestation, #corruption, and #indigenousrights abuses for #palmoil. Calls mount for…

West Papuan Indigenous Women Fight Land Seizures

Indigenous Melanesian women in West Papua fight land seizures for palm oil and sugar plantations, protecting their ancestral rights. Join #BoycottPalmOil

Greasing the Wheels of Colonialism: Palm Oil Industry in West Papua

A landmark study published in Global Studies Quarterly in April 2025 has revealed that the rapid expansion of the #palmoil industry in #WestPapua is not only fuelling #deforestation, #ecocide and environmental destruction but…

Load more posts

Something went wrong. Please refresh the page and/or try again.

Take Action in Five Ways

1. Join the #Boycott4Wildlife on social media and subscribe to stay in the loop: Share posts from this website to your own network on Twitter, Mastadon, Instagram, Facebook and Youtube using the hashtags #Boycottpalmoil #Boycott4Wildlife.

Enter your email address

Sign Up

Join 3,171 other subscribers2. Contribute stories: Academics, conservationists, scientists, indigenous rights advocates and animal rights advocates working to expose the corruption of the palm oil industry or to save animals can contribute stories to the website.

Wildlife Artist Juanchi Pérez

Mel Lumby: Dedicated Devotee to Borneo’s Living Beings

Anthropologist and Author Dr Sophie Chao

Health Physician Dr Evan Allen

The World’s Most Loved Cup: A Social, Ethical & Environmental History of Coffee by Aviary Doert

How do we stop the world’s ecosystems from going into a death spiral? A #SteadyState Economy

3. Supermarket sleuthing: Next time you’re in the supermarket, take photos of products containing palm oil. Share these to social media along with the hashtags to call out the greenwashing and ecocide of the brands who use palm oil. You can also take photos of palm oil free products and congratulate brands when they go palm oil free.

https://twitter.com/CuriousApe4/status/1526136783557529600?s=20

https://twitter.com/PhillDixon1/status/1749010345555788144?s=20

https://twitter.com/mugabe139/status/1678027567977078784?s=20

4. Take to the streets: Get in touch with Palm Oil Detectives to find out more.

5. Donate: Make a one-off or monthly donation to Palm Oil Detectives as a way of saying thank you and to help pay for ongoing running costs of the website and social media campaigns. Donate here

Pledge your support#belize #boycottPalmOil #boycottpalmoil #childLabour #childSlavery #climatechange #community #goldMining #humanRights #hunger #indigenous #indigenousActivism #indigenousKnowledge #indigenousRights #indigenousrights #landRights #landgrabbing #landrights #maya #mexico #palmOil #poverty #slavery #wildfires

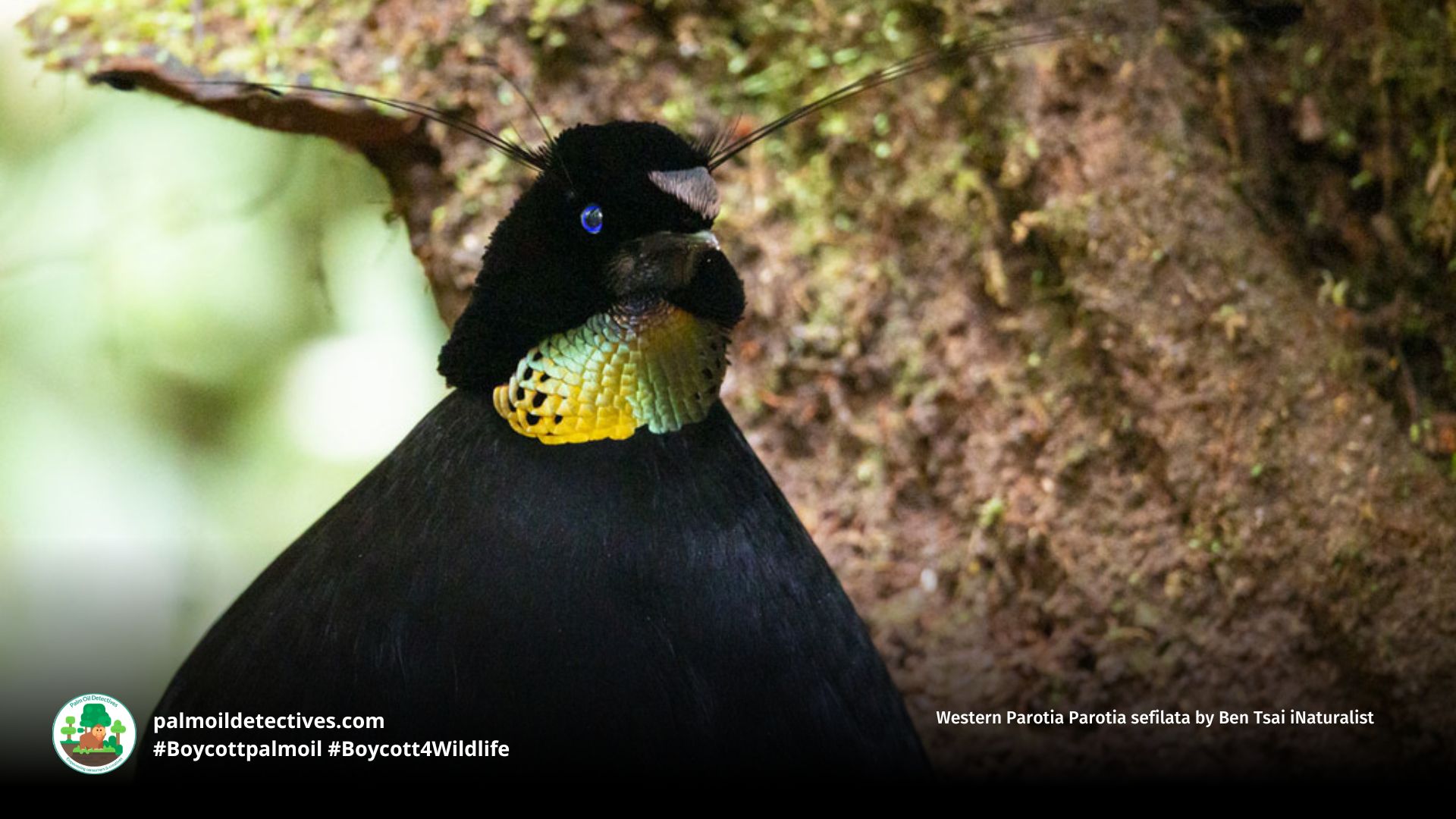

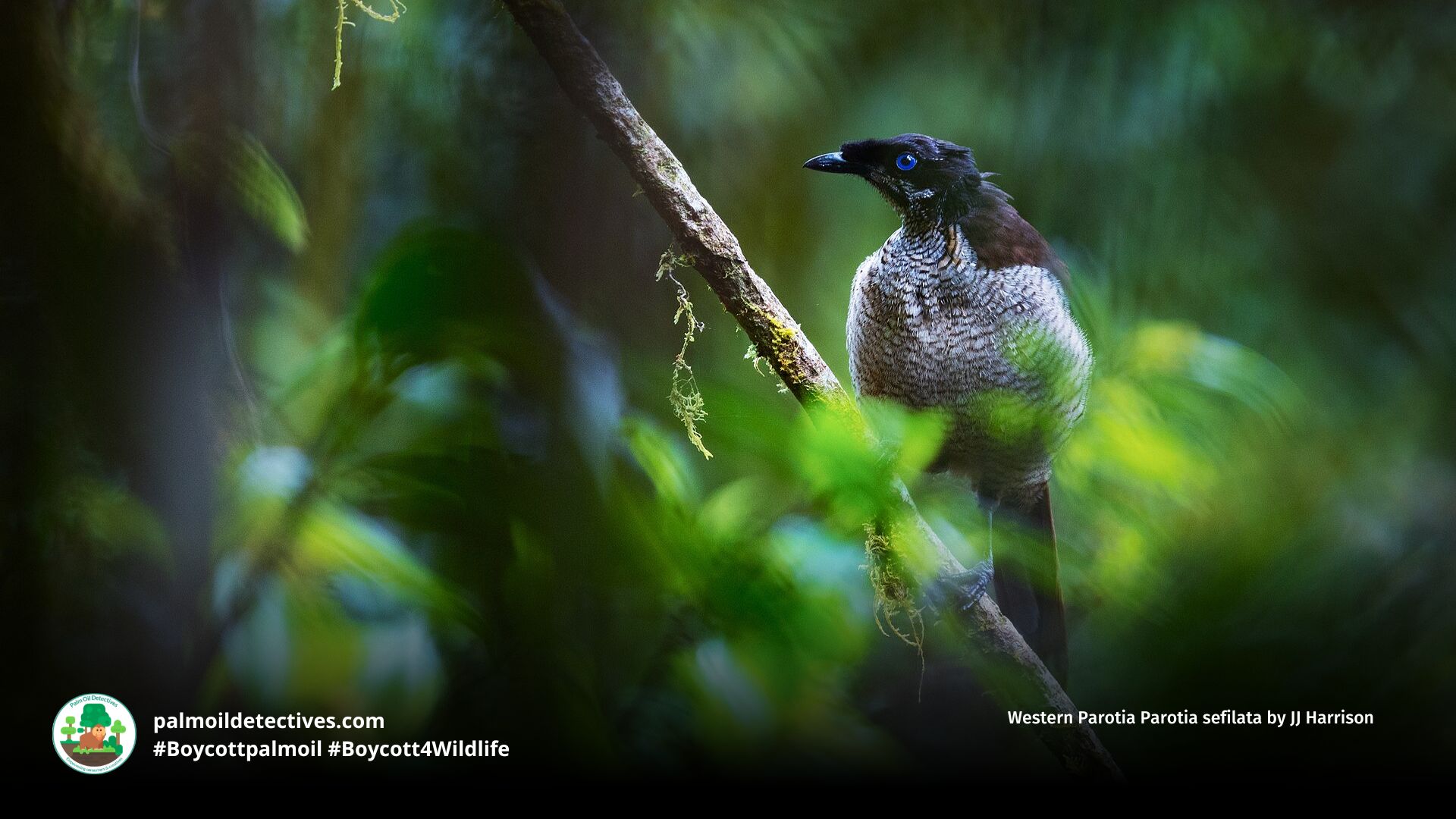

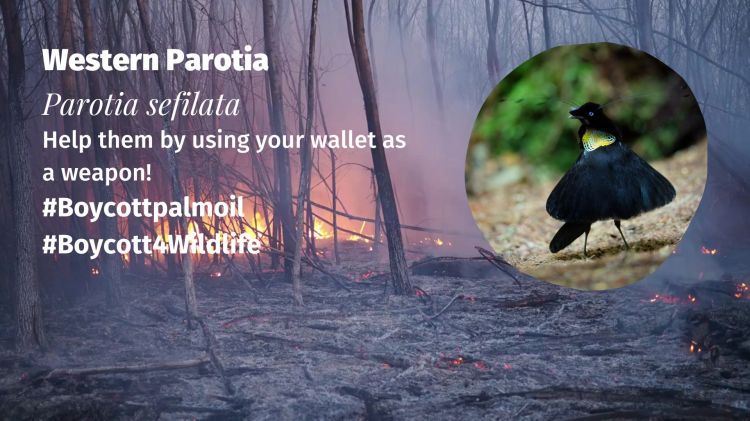

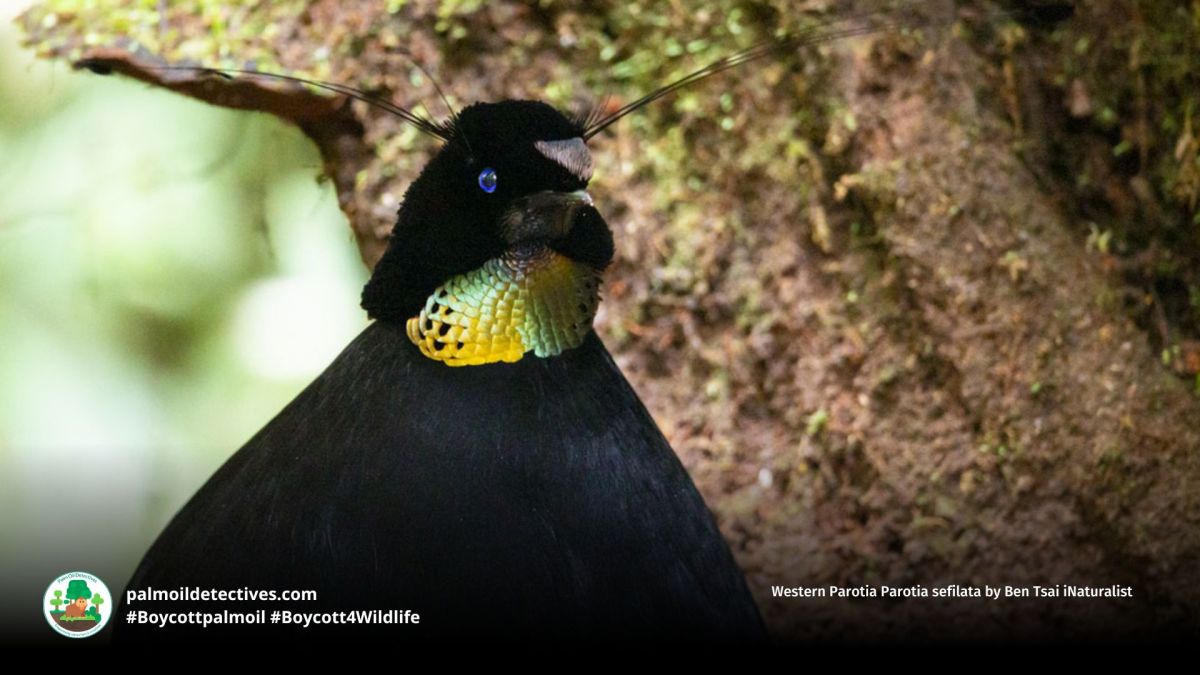

Western Parotia Parotia sefilata

Western Parotia Parotia sefilata

Location: West Papua (Illegally occupied by Indonesia)

Found exclusively in the montane forests of the Vogelkop Peninsula and Wandammen Mountains in Indonesian-occupied West Papua, this species is confined to isolated pockets of ancient, cloud-draped rainforest.

The Western Parotia Parotia sefilata, also called the Arfak Parotia, is a stunning bird-of-paradise of #WestPapua known for their mesmerising, ballerina-like courtship dance. Male #birds fan their iridescent flank plumes into a skirt and dazzle females with precise steps and shimmering throat shields. Although listed as Least Concern in 2016, this designation is dangerously outdated. The forests these rare birds call home have suffered catastrophic #deforestation in recent years due to the explosion of #palmoil plantations. These once-pristine regions are now fragmented and rapidly vanishing. Immediate action is needed to protect the Western Parotia from becoming the next victim of extinction.#BoycottPalmOil #Boycott4Wildlife

Unusual behaviours like mounting reveal complexity to the lives of Western #Parotia, thrilling #birds of paradise in #WestPapua. #Palmoil is a major threat. Fight for them and indigenous peoples #Boycottpalmoil #Boycott4Wildlife @palmoildetect https://palmoildetectives.com/2026/01/25/western-parotia-parotia-sefilata/

Share to BlueSky Share to TwitterWith jet black plumage 🖤 and bright green 💚 wattles, male Western Parotia #birds 🐦🦜🦚 of paradise gleam like scaly armour when they dance 🎶 Resist against their #extinction in #WestPapua when you #Boycottpalmoil 🌴🚫 #Boycott4Wildlife @palmoildetect https://palmoildetectives.com/2026/01/25/western-parotia-parotia-sefilata/

Share to BlueSky Share to TwitterAppearance & Behaviour

Male Western Parotias are instantly recognisable by their jet-black plumage, metallic green wattles that gleam like scaled armour, and three distinctive wire-like head plumes that curl outward from each side of the crown—features that inspired the species name, derived from the Latin sex filum, meaning ‘six threads.’ A dazzling inverted silver triangle on their head flashes during display, perfectly offset by their elegant black flank plumes which form a flared skirt in courtship. Females are more subdued, clad in streaky brown feathers, allowing them to blend into the forest understorey.

This species of bird-of-paradise is polygynous. Males gather in exploded leks—loosely spaced display grounds—where they clear leaf-littered forest floors to create courts. On these makeshift stages, they perform intricate displays to attract females, combining pirouettes, head bobs, feather shimmers, and rapid shakes. A 2024 behavioural study also observed rare alternative mating tactics, including homosexual mounting and sneak copulation attempts by female-plumaged birds, suggesting untapped behavioural complexity (MacGillavry et al., 2024).

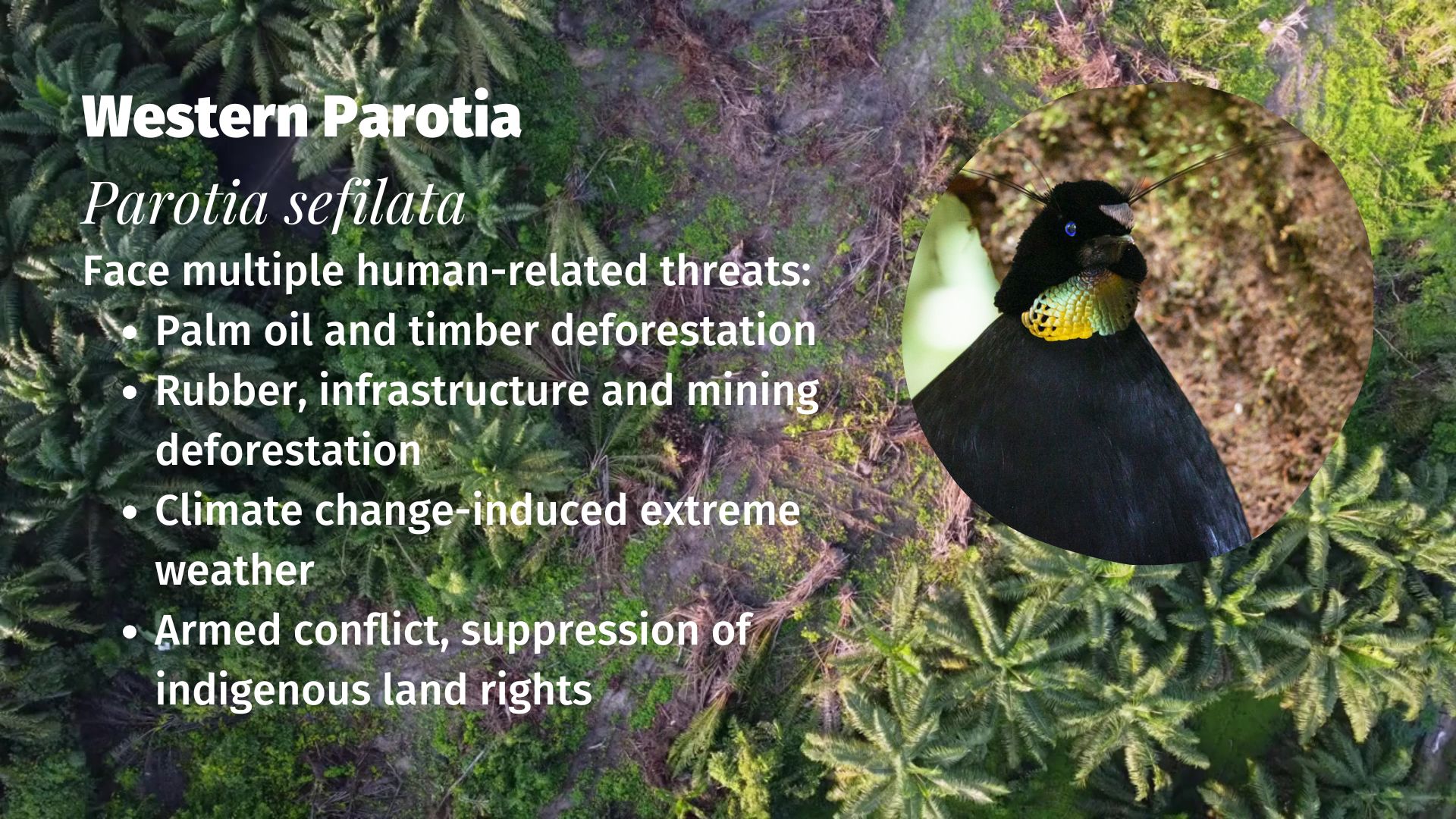

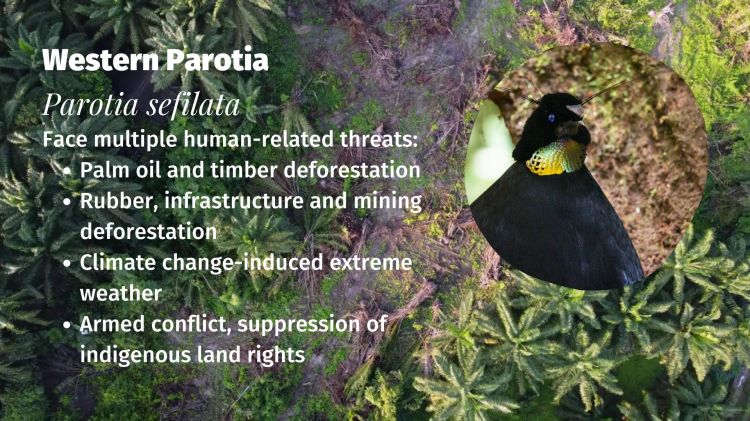

Threats

The Western Parotia is officially listed as Least Concern, but this 2016 classification dangerously underrepresents their current reality. Since that assessment, massive deforestation for timber and palm oil has devastated much of their limited range, particularly across the Vogelkop Peninsula and Wandammen Mountains. The threats are mounting and accelerating due to the following drivers:

Palm oil deforestation

Large-scale clearing of primary rainforest to make way for industrial palm oil plantations is now rampant across the Bird’s Head (Vogelkop) Peninsula. Even remote montane forests where Western Parotias lek and nest are not safe, as new roads are cut to expand plantation frontiers.

Timber deforestation

Commercial timber extraction is removing centuries-old forest giants that the Western Parotia depends on for fruit, foraging and nesting. Logging roads also fragment habitat, increase fire risk, and provide access to previously undisturbed ecosystems.

Deforestation for mining, rubber and infrastructure projects

Government-backed agribusiness schemes are encouraging monocultures such as oil palm and rubber, which completely erase the forest understory and tree canopy vital for the Parotia’s food and shelter.

Mining concessions in West Papua—often enforced with military support—are rapidly opening up forests in the Wandammen Mountains, overlapping with the Parotia’s habitat. Road construction to access mines and plantations is fragmenting the landscape irreparably.

Climate change-induced extreme weather

The species is restricted to highland forest. As temperatures rise and human pressures encroach from below, their montane habitat may shrink to mountaintop fragments, leaving no room for retreat.

Colonial exploitation, military conflict and suppression of Indigenous land rights:

Indigenous Melanesians have stewarded Papuan forests for millennia. Today, state and corporate projects continue to override Indigenous consent, leading to ecological destruction and social injustice hand-in-hand.

These combined threats pose a serious and immediate danger to the survival of the Western Parotia. Without urgent action to halt deforestation and recognise Indigenous land sovereignty, the species could slide rapidly toward extinction unnoticed.

Geographic Range

Western Parotias are found exclusively in the montane and submontane rainforests of the Vogelkop Peninsula and the Wandammen Mountains in West Papua. They are forest specialists, requiring old-growth rainforest to support their complex courtship behaviour and nesting needs. Since their last assessment in 2016, widespread forest loss has occurred across these regions, particularly from illegal logging and palm oil expansion, putting their long-term survival in serious jeopardy.

Diet

Western Parotias primarily feed on fruits—especially figs—and supplement their diet with arthropods. Their foraging occurs at various forest levels, but they prefer mid-canopy and understorey, where fruiting trees and insect-rich foliage are abundant.

Mating and Reproduction

Courtship and nesting behaviour are marked by sexual division of labour. Only the female builds the nest and raises the chick. Nests are often camouflaged in dense foliage. Although the precise breeding season remains unclear, it is believed to vary by elevation and fruiting cycles. Male courtship is heavily influenced by evolutionary modularity in display traits, which have diverged over time, giving rise to the extravagant variety seen across the Parotia genus (Scholes, 2008).

FAQs

How many Western Parotias are left in the wild?

There are no exact population estimates for the Western Parotia. The IUCN has classified them as Least Concern, but this was based on assessments from 2016. Since then, vast tracts of their habitat have been lost. Without a recent survey, the current population trend is unknown, but it is likely decreasing due to ongoing deforestation (BirdLife International, 2016).

How long do Western Parotias live?

In the wild, birds-of-paradise often live between 5 to 10 years, though lifespan data for this species is limited. In captivity, related species have reached over 15 years, but no long-term studies exist for Parotia sefilata specifically.

What challenges do conservationists face protecting this species?

Conservation of the Western Parotia is complicated by a lack of recent data and the remoteness of their habitat. The Vogelkop and Wandammen regions are undergoing rapid transformation due to illegal logging and palm oil expansion, often facilitated by state-backed infrastructure projects. These forests also fall within contested indigenous lands, and conservation solutions must be rooted in indigenous sovereignty to be effective.

Is the Western Parotia affected by the exotic pet trade?

Unlike parrots and smaller songbirds, Western Parotias are not commonly targeted for the exotic pet trade, likely due to their remote habitat and specialised diet. However, increased accessibility due to road construction could change this. It is essential to remain vigilant and oppose any wildlife trafficking.

Take Action!

Use your wallet as a weapon to stop extinction by boycotting palm oil. Always choose products that are 100% palm oil-free to avoid contributing to the deforestation that is pushing the Western Parotia closer to extinction. Support indigenous-led conservation efforts in West Papua and call for greater transparency around the spread of monoculture plantations. Protect the mesmerising courtship rituals of these remarkable birds by fighting to keep their forests standing. #BoycottPalmOil #Boycott4Wildlife #Vegan #BoycottMeat

Support the Western Parotia by going vegan and boycotting palm oil in the supermarket, it’s the #Boycott4Wildlife

Support the conservation of this species

This animal has no protections in place. Read about other forgotten species here. Create art to support this forgotten animal or raise awareness about them by sharing this post and using the #Boycottpalmoil #Boycott4Wildlife hashtags on social media. Also you can boycott palm oil in the supermarket.

Further Information

BirdLife International. (2016). Parotia sefilata. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2016: e.T22706181A93913206. Retrieved 6 April 2025, from https://www.iucnredlist.org/species/22706181/93913206

MacGillavry, T., Janiczek, C., & Fusani, L. (2024). Video evidence of mountings by female-plumaged birds of paradise (Aves: Paradisaeidae) in the wild: Is there evidence of alternative mating tactics? Ethology. https://doi.org/10.1111/eth.13451

Scholes, E. (2008). Evolution of the courtship phenotype in the bird of paradise genus Parotia (Aves: Paradisaeidae): homology, phylogeny, and modularity. Biological Journal of the Linnean Society, 94(3), 491–504. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1095-8312.2008.01012.x

Wikipedia contributors. (n.d.). Western parotia. Wikipedia. Retrieved 6 April 2025, from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Western_parotia

How can I help the #Boycott4Wildlife?

Take Action in Five Ways

1. Join the #Boycott4Wildlife on social media and subscribe to stay in the loop: Share posts from this website to your own network on Twitter, Mastadon, Instagram, Facebook and Youtube using the hashtags #Boycottpalmoil #Boycott4Wildlife.

Enter your email address

Sign Up

Join 3,176 other subscribers2. Contribute stories: Academics, conservationists, scientists, indigenous rights advocates and animal rights advocates working to expose the corruption of the palm oil industry or to save animals can contribute stories to the website.

Wildlife Artist Juanchi Pérez

Mel Lumby: Dedicated Devotee to Borneo’s Living Beings

Anthropologist and Author Dr Sophie Chao

Health Physician Dr Evan Allen

The World’s Most Loved Cup: A Social, Ethical & Environmental History of Coffee by Aviary Doert

How do we stop the world’s ecosystems from going into a death spiral? A #SteadyState Economy

3. Supermarket sleuthing: Next time you’re in the supermarket, take photos of products containing palm oil. Share these to social media along with the hashtags to call out the greenwashing and ecocide of the brands who use palm oil. You can also take photos of palm oil free products and congratulate brands when they go palm oil free.

https://twitter.com/CuriousApe4/status/1526136783557529600?s=20

https://twitter.com/PhillDixon1/status/1749010345555788144?s=20

https://twitter.com/mugabe139/status/1678027567977078784?s=20

4. Take to the streets: Get in touch with Palm Oil Detectives to find out more.

5. Donate: Make a one-off or monthly donation to Palm Oil Detectives as a way of saying thank you and to help pay for ongoing running costs of the website and social media campaigns. Donate here

Pledge your supportLearn about other animals endangered by palm oil and other agriculture

GlobalSouth America S.E. AsiaIndiaAfricaWest Papua & PNG

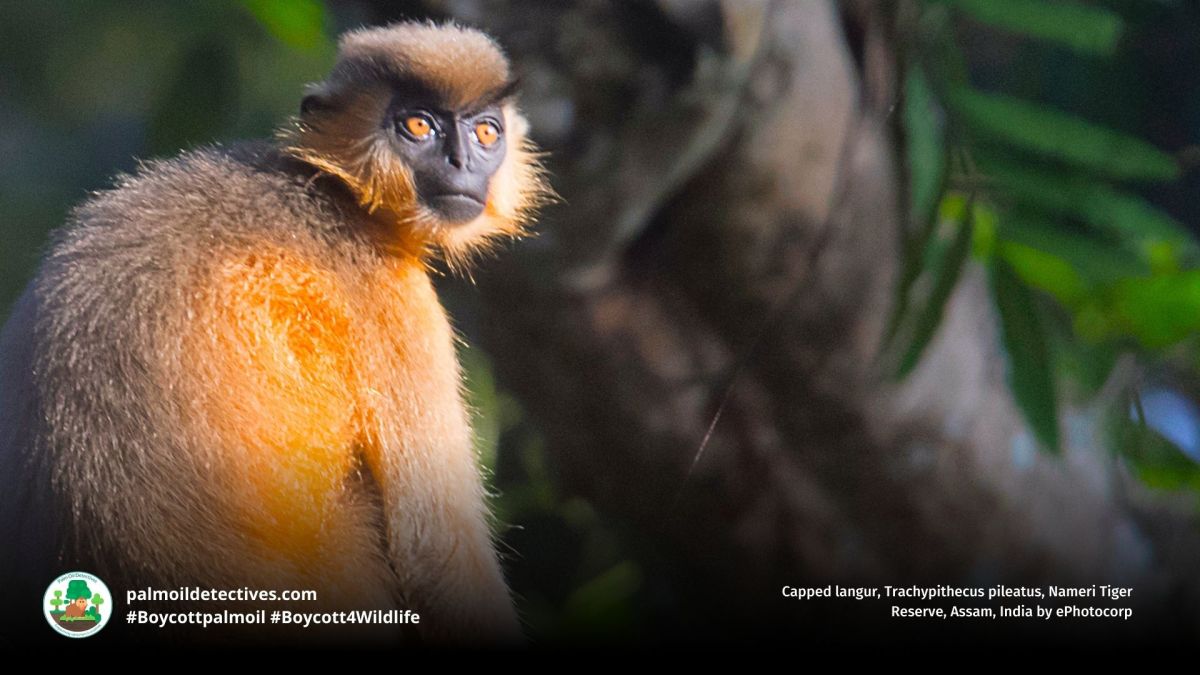

Capped Langur Trachypithecus pileatus

Mountain Tapir Tapirus pinchaque

Saola Pseudoryx nghetinhensis

Tucuxi Sotalia fluviatilis

Frill-Necked Lizard Chlamydosaurus kingii

Grey Crowned Crane Balearica regulorum

Learn about “sustainable” palm oil greenwashing

Read more about RSPO greenwashing

Lying Fake labelsIndigenous Land-grabbingHuman rights abusesDeforestation Human health hazardsA 2019 World Health Organisation (WHO) report into the palm oil industry and RSPO finds extensive greenwashing of palm oil deforestation and the murder of endangered animals (i.e. biodiversity loss)

Read more

#animals #Bird #birds #Birdsong #Boycott4wildlife #BoycottMeat #BoycottPalmOil #deforestation #EndSongbirdTrade #extinction #ForgottenAnimals #FreeWestPapua #gold #goldMining #hunting #indigenous #military #PalmOil #palmOilDeforestation #palmoil #Parotia #poaching #songbird #songbirds #vegan #vulnerable #VulnerableSpecies #WestPapua #WesternParotiaParotiaSefilata #WestPapua

Indigenous Empowerment to Reverse Amazonia’s Mineral Demand

Illegal #mining for minerals like #gold and cassiterite, the latter used for renewable energy, is driving #deforestation in Indigenous #Amazonia. Countries like #Brazil, #Suriname and #Guyana face the challenge of conserving forests, protecting #indigenous peoples, biodiversity whilst also meeting international resource demands. Empowering indigenous peoples to care for biodiversity rich areas of Amazonia is key to saving them for future generations. Act now to protect Indigenous lands and wildlife. #BoycottGold4Yanomami #Boycott4Wildlife.

The drive for #mineral #mining in #Amazonia is driving #indigenous peoples and endangered #animals towards #extinction. Help and fight for them when you #BoycottGold4Yanomami #Boycott4Wildlife @palmoildetect @barbaranavarro https://wp.me/pcFhgU-8TF

Share to BlueSky Share to TwitterKey to tempering #Amazonia’s mineral #mining demand for #gold and other metals is prioritising #Indigenous #empowerment #landrights and indigenous sovereignty #BoycottGold4Yanomami #Boycott4Wildlife @barbaranavarro @palmoildetect https://wp.me/pcFhgU-8TF

Share to BlueSky Share to TwitterWritten by Yolanda Ariadne Collins, Lecturer, International Relations, University of St Andrews. This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Mining for gold in Suriname. Yolanda Ariadne Collins, CC BY-NC-ND

Mining for gold in Suriname. Yolanda Ariadne Collins, CC BY-NC-NDIllegal mining for critical minerals needed for the global renewable energy transition is increasingly driving deforestation in Indigenous lands in the Amazon.

In recent years, these illegal miners, who are often self-employed, mobile and working covertly, have expanded their gold mining operations to include cassiterite or “black gold”, a critical mineral essential for the renewable energy transition. Cassiterite is used to make coatings for solar panels, wind turbines and other electronic devices. Brazil, one of the world’s largest exporters of this mineral, is now scrambling to manage this new threat to its Amazon forests.

The need for developing countries such as Brazil to conserve their forests for the collective global good conflicts with the increasing demand for their resources from international markets. To complicate matters further, both the renewable energy transition and the conservation of the Amazon are urgent priorities in the global effort to arrest climate change.

But escalating deforestation puts these forests at risk of moving from a carbon sink – with trees absorbing more carbon dioxide from the atmosphere than they release – to a carbon source, whereby trees release more carbon dioxide than they absorb as they degrade or are burnt.

Indigenous and other forest-dwelling communities are central to forest conservation. In 2014, I spent a year living in Guyana and Suriname, two of the nine countries that share the Amazon basin. I studied the effectiveness of international policies that aim to pay these countries to avoid deforestation.

I met with members of communities who were bearing the brunt of the negative effects of small-scale gold mining, such as mercury poisoning and loss of hunting grounds. For decades, mining for gold, which threatens communities’ food supply and traditional ways of life, has been the main driver of deforestation in both countries.

Small-scale mining operations can damage both communities and the natural world. Gold mining, which generates gold for export used for jewellery and electronics, usually begins with the removal of trees and vegetation from the topsoil, facilitated by mechanical equipment such as excavators. Next, the miners dig up sediment, which gets washed with water to extract any loose flecks of gold.

Miners usually then add mercury, a substance that’s known to be toxic and incredibly damaging to human health, to washing pans to bind the gold together and separate it from the sediment. They then burn the mercury away, using lighters and welding gear. During this process, mercury is inhaled by miners and washed into nearby waterways, where it can enter the food chain and poison fish and other species, including humans.

My new book, Forests of Refuge: Decolonizing Environmental Governance in the Amazonian Guiana Shield, highlights the colonial histories through which these countries were created. These histories continue to inform the land-use practices of people and forest users there. Having seen the dynamics firsthand, I argue that these unaddressed histories limit the effectiveness of international policies aimed at reducing deforestation.

Some of the policies’ limitations are rooted in their inattentiveness to the roughly five centuries of colonialism through which these countries were formed. These histories had seen forests act as places of refuge and resistance for Indigenous and Afro-descendant communities. I believe that power structures created by these histories need to be tackled through processes of decolonisation, which includes removing markets from their central place in processes of valuing nature, and taking seriously the worldviews of Indigenous and other forest-dependent communities.

But since 2014, small-scale mining-led deforestation in the Amazon has persisted, and even increased. The increase in mining worldwide, driven partly by the renewable energy transition, indicates that these power structures might be harder to shift than ever before.

Added pressure

When crackdowns on illegal gold mining took place in Brazil in the 1970s and ’80s, miners moved en masse to nearby Guyana and Suriname, taking their environmentally destructive technologies with them. Illegal miners of cassiterite are now following a similar pattern, showing that the global effort to reduce deforestation cannot simply focus on a single commodity as a driver of deforestation on the ground.

My work shows that the challenge of mining-led deforestation in the Amazon is rooted in historically informed, global power structures that position the Amazon and its resources as available for extraction by industries and governments in wealthier countries. These groups of people are now seeking to reduce their disproportionately high emissions through technological solutions and not through behavioural change.

These tensions also have roots in the readiness of governments and forest users in postcolonial countries, like Brazil and Guyana, to respond positively and unquestioningly to international demand for these resources.

In the Amazon, outcomes are affected by whether different groups of people have access to livelihoods that do not drive deforestation, such as those based on non-timber forest products. The situation is further shaped by the extent to which governments can work together to ensure that crackdowns in one part of the Amazon, such as Brazil, do not just drive deforestation elsewhere to Suriname, for example.

Until the power structure that disadvantages Indigenous and other historically marginalised groups changes, the negative effects of developing technologies to “save” the planet will continue to disproportionately burden these groups, even as their current way of life remains critical to supporting sustainable development outcomes.

Written by Yolanda Ariadne Collins, Lecturer, International Relations, University of St Andrews. This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

ENDS

https://youtu.be/RLsqyADpgn0?si=BniKvXzjQFeZXUoV

Read more about gold mining, indigenous rights and its cost to animals

Western Parotia Parotia sefilata

Western Parotias AKA Arfak Parotias are stunning bird-of-paradise of West Papua known for their mesmerising dances. Palm oil and mining ecocide are threats

Read more

Indigenous Peoples Fight Climate Change

After wildfires, Belize’s indigenous people rebuild stronger based on “se’ komonil”: reciprocity, solidarity, gender equity, togetherness and community.

Read more

Tucuxi Sotalia fluviatilis

Tucuxi, small freshwater dolphins of Peru Ecuador Colombia and Brazil are Endangered due to fishing nets, deforestation, mercury poisoning from gold mining.

Read more

An Action Plan for Amazon Droughts: The Time is Now!

The fertile lungs of our planet, the Amazon jungle faces severe drought due to El Niño, climate change, and deforestation for agriculture like palm oil, soy and meat. This along with gold mining,…

Read more

Brazilian three-banded armadillo Tolypeutes tricinctus

The Brazilian three-banded #armadillo Tolypeutes tricinctus, known as “tatu-bola” in Portuguese, is a rare and unique species native to #Brazil. With the ability to roll into a near-impenetrable ball, this endearing behaviour has…

Read more Load more postsSomething went wrong. Please refresh the page and/or try again.

Take Action in Five Ways

1. Join the #Boycott4Wildlife on social media and subscribe to stay in the loop: Share posts from this website to your own network on Twitter, Mastadon, Instagram, Facebook and Youtube using the hashtags #Boycottpalmoil #Boycott4Wildlife.

Enter your email address

Sign Up

Join 3,178 other subscribers2. Contribute stories: Academics, conservationists, scientists, indigenous rights advocates and animal rights advocates working to expose the corruption of the palm oil industry or to save animals can contribute stories to the website.