Unsupported type or deleted object

Tucuxi Sotalia fluviatilis

Tucuxi Sotalia fluviatilis

IUCN Red List Status: Endangered

Location: #Brazil, #Peru, #Colombia, #Ecuador

Found throughout the #Amazon and Solimões River systems, including major tributaries and large lakes. Their range spans lowland rainforest areas of Brazil, southeastern Colombia, eastern Ecuador, and southern Peru.

The #Tucuxi, a small freshwater #dolphin of #Peru, #Ecuador, #Colombia and #Brazil now faces a dire future. Once common throughout the Amazon River system, they are now listed as #Endangered due to accelerating population declines. Threats include drowning in fishing nets, deforestation, mercury poisoning from gold mining, #palmoil run-off, oil drilling, and dam construction. A shocking 97% decline was recorded over 23 years in a single Amazon reserve. Without urgent action, this elegant and playful river dolphin could vanish from South America’s waterways. Use your wallet as a weapon against extinction. Choose palm oil-free, and #BoycottGold #BoycottPalmOil #Boycott4Wildlife

Playful and intelligent #Tucuxi are small #dolphins 🐬 of #Amazonian rivers in #Peru 🇵🇪 #Brazil 🇧🇷 #Ecuador 🇪🇨 and #Colombia 🇨🇴. #PalmOil and #GoldMining are major threats 😿 Fight for them! #BoycottGold #BoycottPalmOil #Boycott4Wildlife @palmoildetect https://palmoildetectives.com/2025/11/23/tucuxi-sotalia-fluviatilis/

Share to BlueSky Share to TwitterClever and joyful #Tucuxi are #dolphins 🐬💙 endangered by #hunting #gold #mining and contamination of the Amazon river 🇧🇷 for #PalmOil #agriculture ☠️ Use your wallet as a weapon and #BoycottGold 🥇🚫 #BoycottPalmOil 🌴🚫 #Boycott4Wildlife @palmoildetect https://palmoildetectives.com/2025/11/23/tucuxi-sotalia-fluviatilis/

Share to BlueSky Share to TwitterAppearance & Behaviour

Tucuxis are often mistaken for their oceanic dolphin cousins due to their streamlined bodies, short beaks, and smooth, pale-to-dark grey skin. But these freshwater dolphins are wholly unique—adapted to life in winding river systems where water levels rise and fall dramatically with the seasons.

What sets them apart is their remarkable intelligence and tightly knit social groups. Tucuxis are playful and curious by nature. They leap from the water in graceful arcs, sometimes spinning mid-air.

The Tucuxi, sometimes called the ‘grey dolphin’ due to their uniform colouring, resembles a smaller oceanic dolphin, with a streamlined body and slender beak. Their colour varies from pale grey on the belly to darker grey or bluish-grey along the back.

They travel in small groups of two to six, displaying coordinated swimming patterns. In rare cases, they may form groups up to 26 individuals, particularly at river confluences. Known for their agility, they leap and spin in the water with a grace that belies their size. Tucuxis are particularly drawn to dynamic habitats like river junctions, where waters mix and fish gather.

Threats

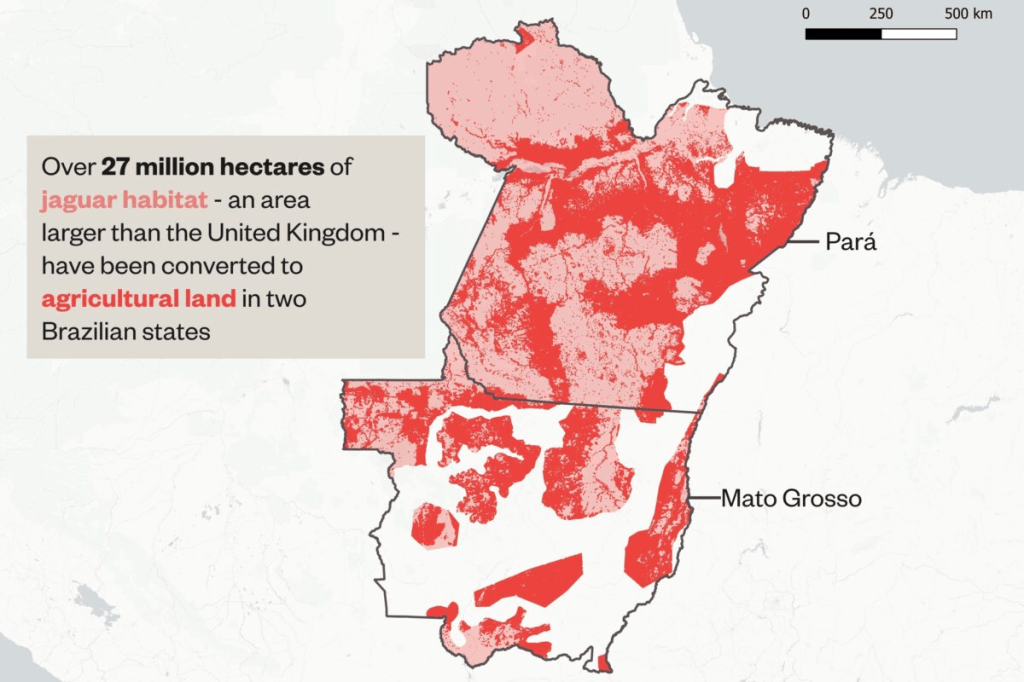

- Widespread deforestation from palm oil plantations Palm oil plantations are rapidly expanding across the Amazon, clearing vast tracts of forest that stabilise riverbanks and filter water. This deforestation leads to increased sedimentation in rivers, altering flow patterns and reducing water clarity—conditions that directly disrupt the Tucuxi’s feeding and movement. Run-off from fertilisers and pesticides used in palm oil monocultures also poisons aquatic ecosystems, harming Tucuxis other Amazonian dolphin species and the fish they rely on.

- Toxic mercury pollution from gold mining Artisanal and illegal gold mining in the Amazon releases massive quantities of mercury into the water, contaminating fish and other aquatic organisms. Tucuxis, as top predators, ingest this mercury through their prey, which accumulates in their tissues and causes neurological damage, weakened immunity, and reproductive failure. Mercury exposure is one of the most insidious threats, as it persists in ecosystems long after mining has ceased.

- Incidental drowning in fishing nets Tucuxis are frequently caught and killed in gillnets and other fishing gear as bycatch. Tucuxis and other Amazonian dolphins often inhabit the same confluence zones and productive fishing grounds targeted by local communities, making entanglement almost inevitable. Many carcasses are never recovered, having either been discarded by fishers or lost to river currents, meaning actual mortality rates are likely far higher than reported.

- Deliberate hunting for use as fish bait Though illegal, Tucuxis continue to be targeted and killed in parts of Brazil, especially near the Mamirauá and Amana Reserves, where they are used as bait in the piracatinga (catfish) fishery. This brutal practice involves harpooning or netting dolphins and using their flesh to lure fish, often alongside the killing of Botos. Despite a national ban, weak enforcement and ongoing demand mean this threat persists in remote and lawless regions.

- Illegal fishing with explosives and toxins In certain areas, particularly in Brazil and Peru, fishers use home-made explosives and poisoned bait to stun or kill fish en masse. These destructive methods harm or kill Tucuxis who are attracted by the sudden appearance of dead or stunned prey. The concussive force of explosions and the ingestion of poisoned prey result in slow, agonising deaths for affected dolphins.

- Construction of hydroelectric dams Dams fragment Tucuxi populations by blocking their movement along river corridors, reducing access to feeding and breeding grounds. These projects alter seasonal water flow, raise water temperatures, and flood critical habitats—conditions that significantly disrupt dolphin ecology. Brazil alone has 74 operational dams in the Amazon basin, with over 400 more planned, posing a long-term existential threat to freshwater cetaceans.

- Run-off and contamination from palm oil, soy and meat agriculture In addition to habitat loss, palm oil and soy plantations along with cattle ranching generates enormous volumes of chemical-laden waste, which enters waterways and poisons aquatic life. This pollution affects Tucuxis both directly and indirectly—exposing them to harmful substances and killing off sensitive fish species. As plantations replace biodiverse forests, the ecosystem becomes less resilient, accelerating the decline of species like the Tucuxi.

- Bioaccumulation of heavy metals and industrial pollutants Tucuxis, like many river dolphins, suffer from exposure to persistent organic pollutants such as PCBs, DDT, and flame retardants, as well as heavy metals like lead and cadmium. These toxins accumulate in dolphin tissues over time, weakening their immune systems, interfering with reproduction, and making them more vulnerable to disease. Contaminants originate from industrial waste, agriculture, and mining, and are now widespread across the Amazon basin.

- Habitat fragmentation from infrastructure and oil development Roads, oil pipelines, and shipping corridors criss-cross many parts of the Tucuxi’s range, slicing through their habitat and increasing the risk of collisions with boats. These developments also bring noise pollution, which can interfere with echolocation and communication. Fragmentation leads to isolated subpopulations, reducing genetic diversity and making recovery more difficult.

Geographic Range

The Tucuxi inhabits the Amazon River basin, spanning: Brazil, Peru, Colombia, Ecuador These river dolphins occur as far west as southern Peru and eastern Ecuador, and as far north as southeastern Colombia. They are notably absent from Bolivia’s Beni/Mamoré system, the Orinoco basin, and upper reaches above major waterfalls or rapids.

Their range includes wide, deep rivers and lakes, avoiding turbulent rapids and shallow areas. Despite overlapping with the Amazon River Dolphin (Inia geoffrensis), Tucuxis do not enter flooded forest habitats and stay closer to main river channels.

Diet

Tucuxis feed on more than 28 species of small, schooling freshwater fish, including members of the characid, sciaenid, and siluriform families. During the dry season, fish are concentrated in shrinking waterways, making them easier to catch. In contrast, flooding season disperses prey into forested areas, beyond the Tucuxi’s reach. They prefer to feed at river junctions and along confluences, where nutrient-rich waters concentrate fish populations.

Mating and Reproduction

Little is known about their mating behaviours. However, individuals appear to remain within familiar ranges for many years, and females likely give birth to a single calf after a long gestation. Calves are dependent for an extended period, learning complex navigation and foraging skills in rapidly changing river systems. The estimated generation length is 15.6 years.

FAQs

How many Tucuxis are left in the wild?

There is no comprehensive global population estimate. However, surveys from 1994–2017 in Brazil’s Mamirauá Reserve show a 7.4% annual decline—amounting to a 97% drop over three generations (da Silva et al., 2020). If this trend reflects the wider Amazon basin, the species could be on the brink of collapse.

How long do Tucuxis live?

Exact lifespans are unknown, but based on reproductive data and life history modelling, their generation length is around 15.6 years (Taylor et al., 2007), suggesting natural lifespans of 30–40 years.

How are palm oil and gold mining affecting Tucuxis?

Out-of-control palm oil expansion results in massive deforestation and run-off, clogging rivers with sediment and toxic agrochemicals. Gold mining adds mercury into aquatic ecosystems, where it bioaccumulates in fish—Tucuxis’ main food source. These pollutants cause reproductive harm, neurological damage, and immune system failure in dolphins.

Do Tucuxis make good pets and should they be kept in zoos?

Absolutely not. Tucuxis are intelligent, wild animals. Keeping them in captivity is deeply cruel and has no conservation benefit. Wild capture destroys families and can devastate local populations. If you care about these dolphins, say no to the exotic pet trade and the cruel zoo trade.

What habitats do they prefer?

Research in Peru’s Pacaya-Samiria Reserve shows that Tucuxis prefer river confluences and wide channels, particularly during the dry season when fish density is higher (Belanger et al., 2022). Feeding activity is especially concentrated in areas where whitewater rivers meet blackwater tributaries, creating nutrient-rich hotspots.

Take Action!

The Tucuxi is vanishing before our eyes. To protect them:

• Boycott palm oil and gold products linked to Amazon destruction.

• Choose fish-free and vegan products to reduce pressure on river ecosystems.

• Support indigenous-led conservation across the Amazon.

• Campaign for a ban on destructive dams, and the end of illegal fishing.

#BoycottPalmOil #Boycott4Wildlife #Vegan #BoycottMeat

Support the Tucuxi by going vegan and boycotting palm oil in the supermarket, it’s the #Boycott4Wildlife

Support the conservation of this species

This animal has no protections in place. Read about other forgotten species here. Create art to support this forgotten animal or raise awareness about them by sharing this post and using the #Boycottpalmoil #Boycott4Wildlife hashtags on social media. Also you can boycott palm oil in the supermarket.

Further Information

Belanger, A., Wright, A., Gomez, C., Shutt, J.D., Chota, K., & Bodmer, R. (2022). River dolphins (Inia geoffrensis and Sotalia fluviatilis) in the Peruvian Amazon: habitat preferences and feeding behaviour. Latin American Journal of Aquatic Mammals, 17(1). https://doi.org/10.5597/lajam00268

da Silva, V., Martin, A., Fettuccia, D., Bivaqua, L. & Trujillo, F. 2020. Sotalia fluviatilis. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2020: e.T190871A50386457. https://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2020-3.RLTS.T190871A50386457.en. Accessed on 06 April 2025.

Monteiro-Neto, C., Itavo, R. V., & Moraes, L. E. S. (2003). Concentrations of heavy metals in Sotalia fluviatilis (Cetacea: Delphinidae) off the coast of Ceará, northeast Brazil. Environmental Pollution, 123(2), 319–324. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0269-7491(02)00371-8

How can I help the #Boycott4Wildlife?

Take Action in Five Ways

1. Join the #Boycott4Wildlife on social media and subscribe to stay in the loop: Share posts from this website to your own network on Twitter, Mastadon, Instagram, Facebook and Youtube using the hashtags #Boycottpalmoil #Boycott4Wildlife.

Enter your email address

Sign Up

Join 3,172 other subscribers2. Contribute stories: Academics, conservationists, scientists, indigenous rights advocates and animal rights advocates working to expose the corruption of the palm oil industry or to save animals can contribute stories to the website.

Wildlife Artist Juanchi Pérez

Mel Lumby: Dedicated Devotee to Borneo’s Living Beings

Anthropologist and Author Dr Sophie Chao

Health Physician Dr Evan Allen

The World’s Most Loved Cup: A Social, Ethical & Environmental History of Coffee by Aviary Doert

How do we stop the world’s ecosystems from going into a death spiral? A #SteadyState Economy

3. Supermarket sleuthing: Next time you’re in the supermarket, take photos of products containing palm oil. Share these to social media along with the hashtags to call out the greenwashing and ecocide of the brands who use palm oil. You can also take photos of palm oil free products and congratulate brands when they go palm oil free.

https://twitter.com/CuriousApe4/status/1526136783557529600?s=20

https://twitter.com/PhillDixon1/status/1749010345555788144?s=20

https://twitter.com/mugabe139/status/1678027567977078784?s=20

4. Take to the streets: Get in touch with Palm Oil Detectives to find out more.

5. Donate: Make a one-off or monthly donation to Palm Oil Detectives as a way of saying thank you and to help pay for ongoing running costs of the website and social media campaigns. Donate here

Pledge your supportLearn about other animals endangered by palm oil and other agriculture

GlobalSouth America S.E. AsiaIndiaAfricaWest Papua & PNG

Frill-Necked Lizard Chlamydosaurus kingii

Grey Crowned Crane Balearica regulorum

Ecuadorean Viscacha Lagidium ahuacaense

Southern Pudu Pudu puda

Blue-streaked Lory Eos reticulata

Blonde Capuchin Sapajus flavius

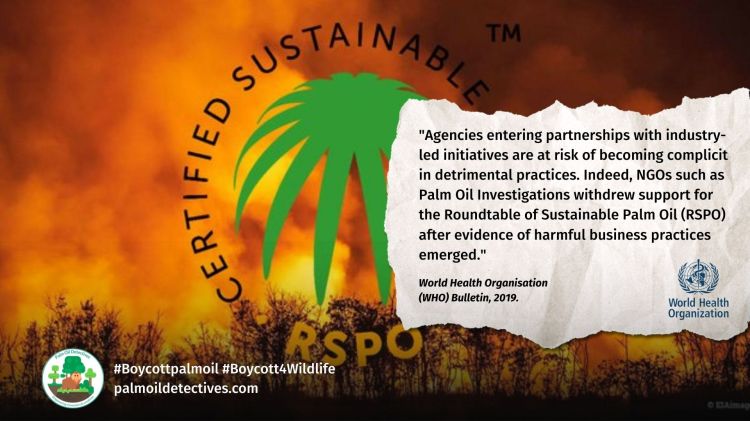

Learn about “sustainable” palm oil greenwashing

Read more about RSPO greenwashing

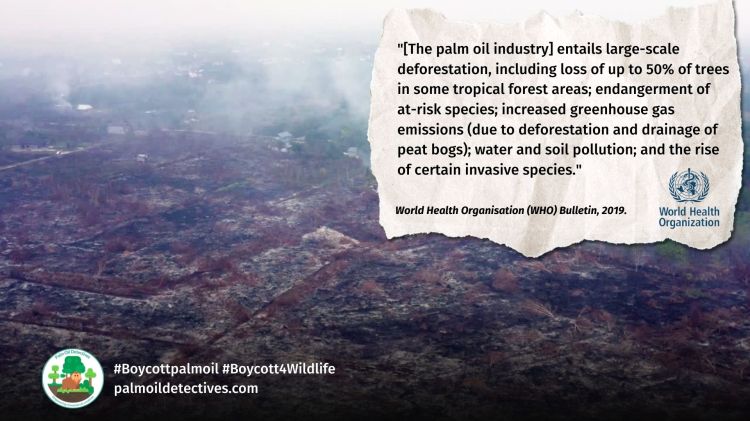

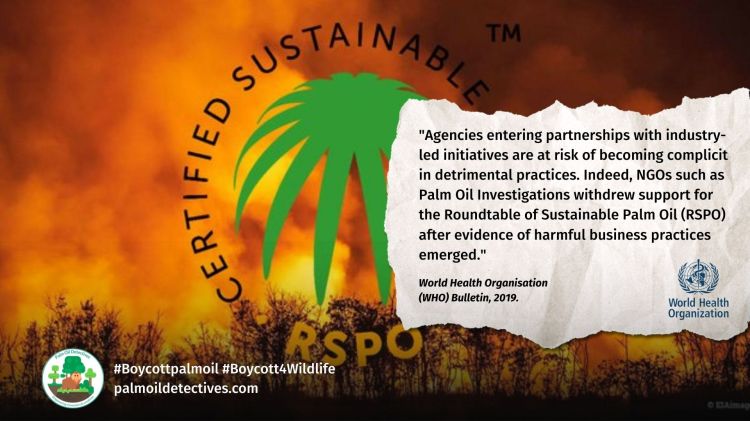

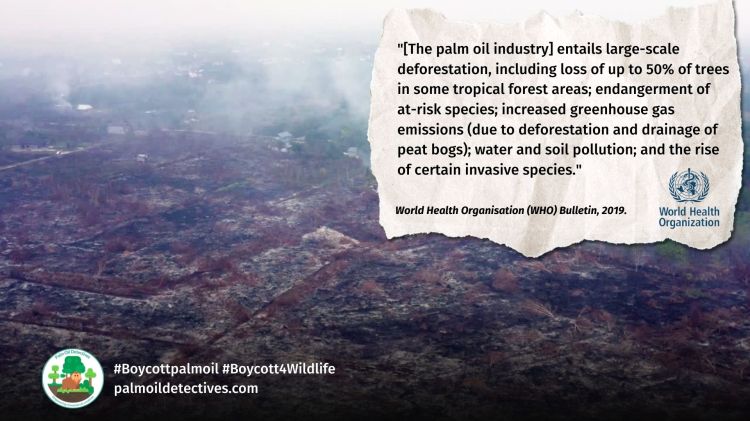

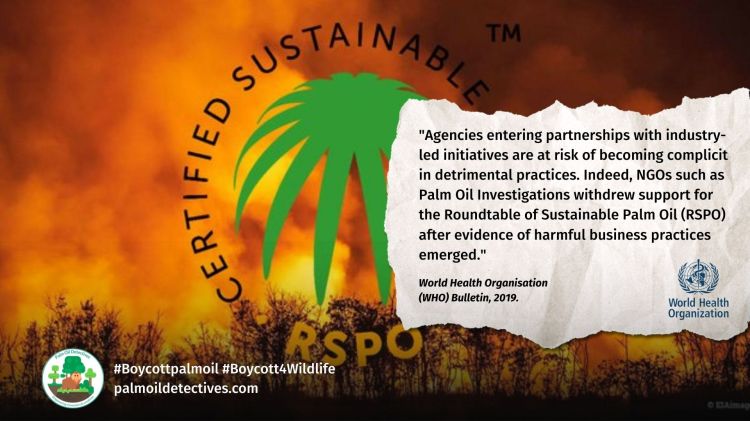

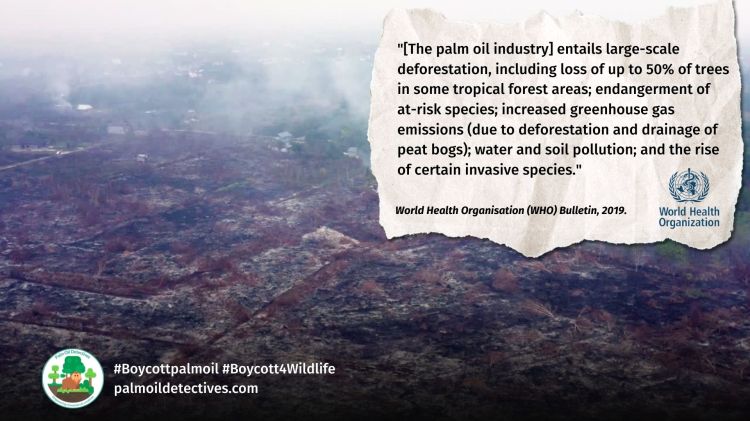

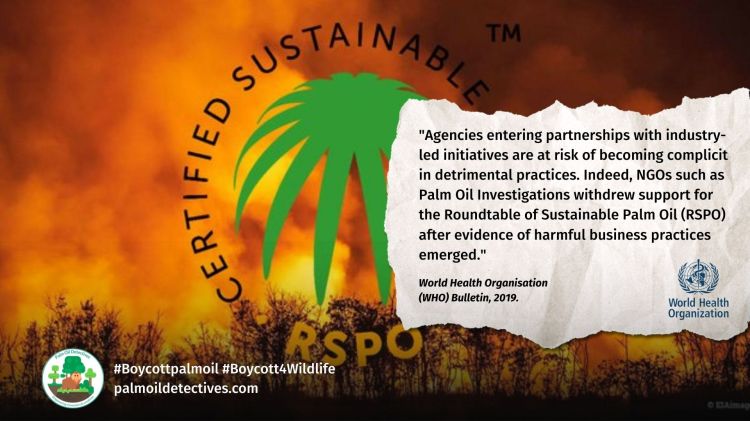

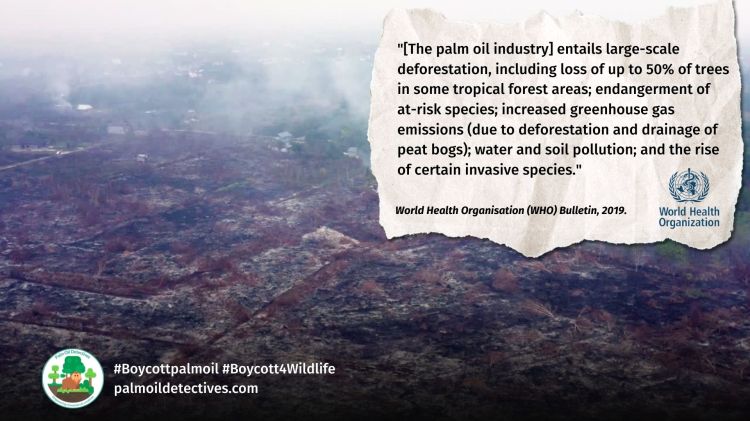

Lying Fake labelsIndigenous Land-grabbingHuman rights abusesDeforestation Human health hazardsA 2019 World Health Organisation (WHO) report into the palm oil industry and RSPO finds extensive greenwashing of palm oil deforestation and the murder of endangered animals (i.e. biodiversity loss)

Read more

#agriculture #amazon #amazonRainforest #amazonia #amazonian #animalCruelty #animals #boycott4wildlife #boycottgold #boycottmeat #boycottpalmoil #brazil #colombia #dams #deforestation #dolphin #dolphins #ecuador #endangered #endangeredSpecies #forgottenAnimals #gold #goldMining #goldmining #humanWildlifeConflict #hunting #hydroelectric #mammal #mining #palmOil #palmOilDeforestation #palmoil #peru #poaching #saynotogold #tucuxi #tucuxiSotaliaFluviatilis #vegan

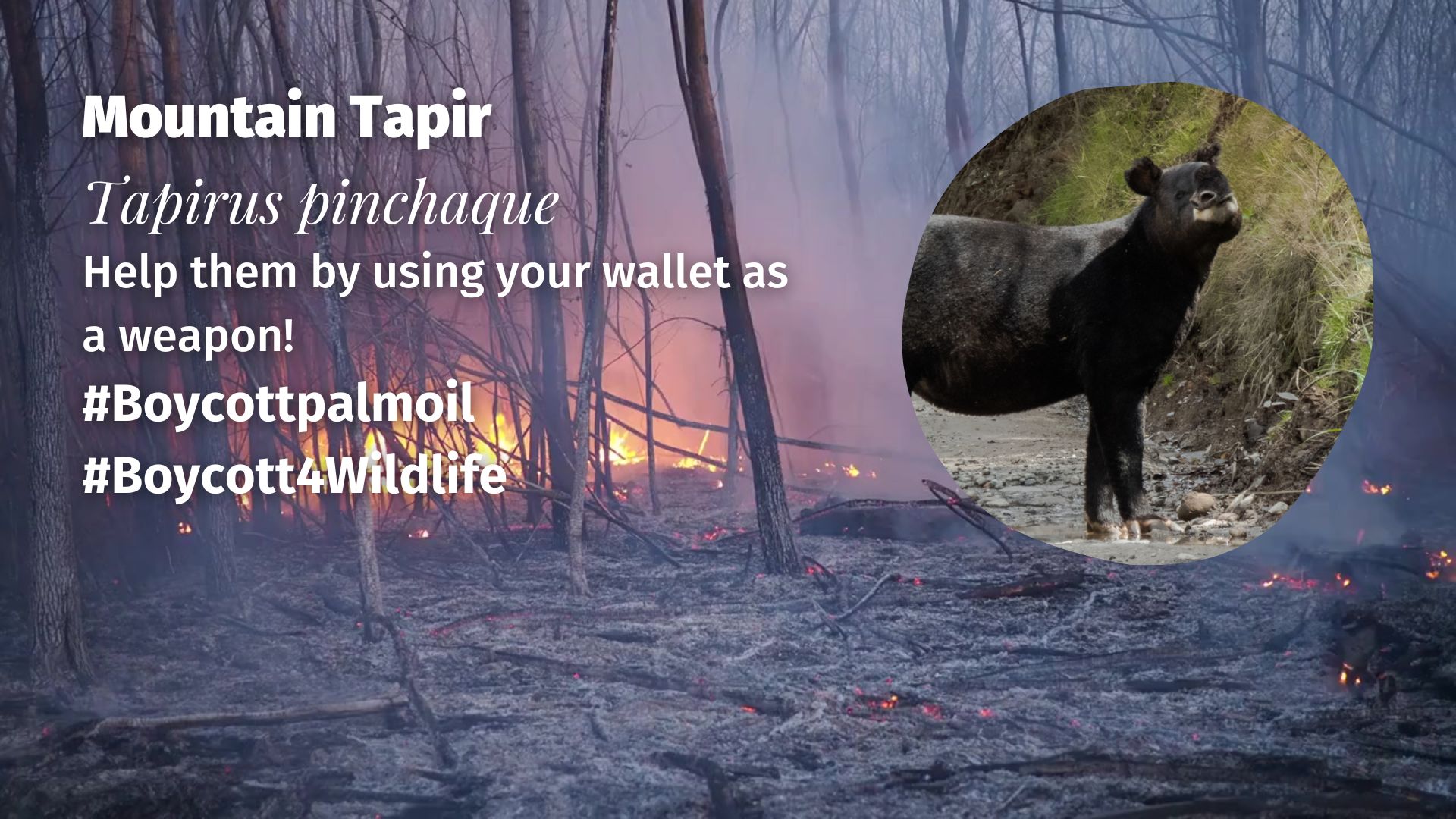

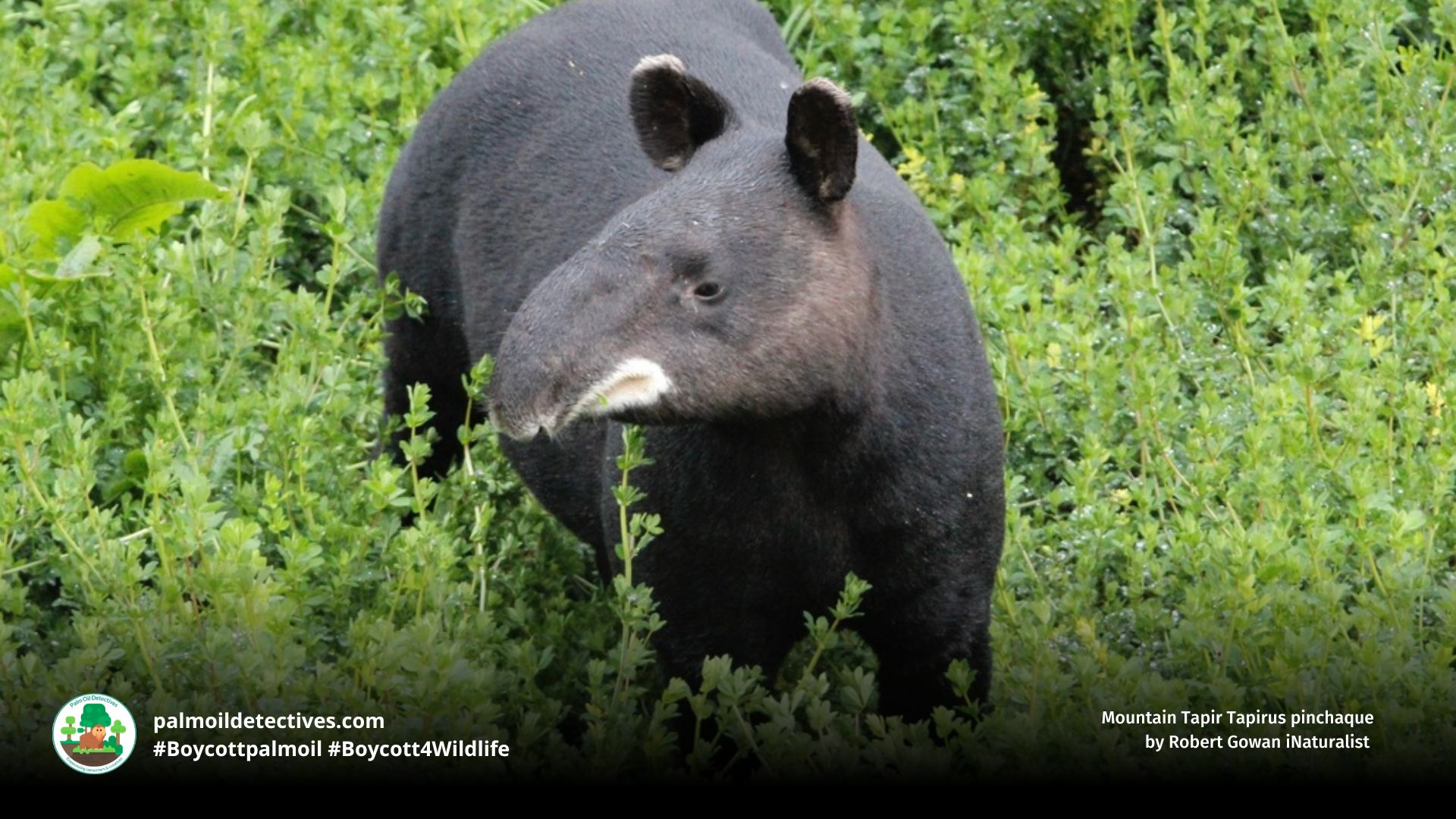

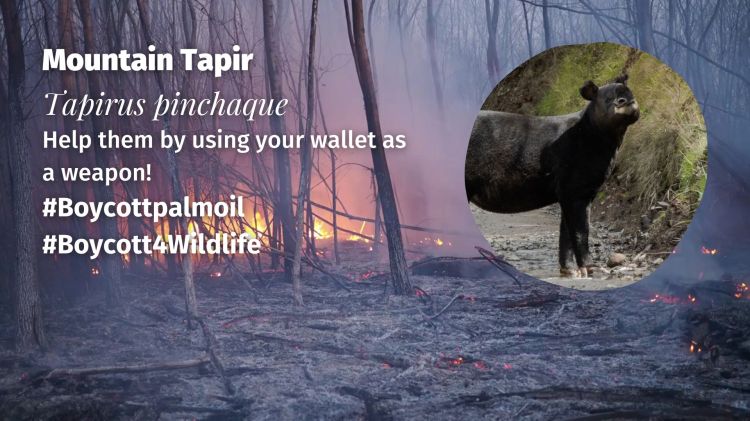

Mountain Tapir Tapirus pinchaque

Mountain Tapir Tapirus pinchaque

IUCN Red List Status: Endangered

Location: Colombia, Ecuador, northern Peru

Mountain Tapirs inhabit the high Andean cloud forests and páramos above 2,000 metres in the northern Andes. They are found in Colombia’s Central and Eastern Cordilleras, throughout Ecuador including Sangay and Podocarpus National Parks, and into northern Peru, notably in Cajamarca and Lambayeque.

The Mountain Tapir Tapirus pinchaque is one of the most threatened large mammals in the northern Andes, currently listed as Endangered. Their populations have declined by over 50% in the past three decades due to habitat loss, illegal hunting, climate change, and rampant mining. With fewer than 2,500 mature individuals remaining, they are quietly disappearing from their mist-shrouded mountain homes. Human encroachment, infrastructure development, and cattle grazing now invade their last strongholds. Without urgent action, they may vanish forever. Use your wallet as a weapon and fight back when you shop #BoycottPalmOil #Boycott4Wildlife and be #BoycottGold

Sweet-natured Mountain #Tapirs of #Ecuador 🇪🇨 #Peru 🇵🇪 and #Colombia 🇨🇴 face serious threats incl. illegal crops, #gold #mining, #palmoil #deforestation and hunting. Help them survive #BoycottPalmOil 🌴⛔️#BoycottGold 🥇⛔️ #Boycott4Wildlife @palmoildetect https://palmoildetectives.com/2025/12/28/mountain-tapir-tapirus-pinchaque/

Share to BlueSky Share to TwitterThe Wooly #Tapir AKA Mountain Tapir gives birth to one calf at a time 🩷😻 They’re #endangered due to a many threats: #climatechange and #pollution from #gold mining. Resist for them! #BoycottPalmOil #BoycottGold 🥇☠️❌ #Boycott4Wildlife @palmoildetect https://palmoildetectives.com/2025/12/28/mountain-tapir-tapirus-pinchaque/

Share to BlueSky Share to TwitterAppearance & Behaviour

Also known as the woolly tapir for their thick, dark, shaggy coat, Mountain Tapirs are built to survive in the cold, damp cloud forests and páramo grasslands. Their dense fur, white lips, and prehensile snout give them an almost prehistoric appearance. These solitary and elusive mammals are primarily nocturnal and crepuscular, navigating dense foliage with ease. Once thought to be loners, long-term studies in Ecuador have revealed that they form small, close-knit family groups, with calves gradually dispersing over several years (Castellanos et al., 2022).

Threats

Deforestation for palm oil, meat agriculture and illicit opium/coca cultivation

Large swathes of Andean cloud forest and páramo are being cleared to make way for palm oil agricultural expansion, cattle grazing, and opium or coca cultivation. These activities are not only destroying core habitat but also breaking up previously connected populations, leaving tapirs isolated and vulnerable to local extinctions. The introduction of cattle into remote tapir refuges has become increasingly common, even inside designated national parks such as Sangay in Ecuador. This leads to trampling of sensitive vegetation, direct competition for food, and destruction of the unique montane ecosystems that Mountain Tapirs rely on for survival.

Illegal hunting for meat, traditional medicine, and cultural uses

Although hunting pressure has declined slightly in Ecuador due to greater public awareness, it remains severe in Colombia and Peru. Tapirs are killed for their meat, and their skins are used to make traditional tools, horse gear, carpets, and bed covers. Additionally, body parts are sold in local markets or prescribed by shamans for use in traditional medicine. In many remote areas, Mountain Tapirs are still being actively poached, and it is now rare to find populations that are not affected by some form of overhunting.

Gold mining and illegal mining causing deforestation and poisoning of ecosystems

Gold mining projects in the northern Peruvian Andes and central Colombia are rapidly destroying the last cloud forest headwaters and páramo ecosystems where tapirs persist. Both legal and illegal mining operations contaminate streams and watersheds with heavy metals and toxic runoff, which has severe consequences for both tapirs and the human communities downstream. Mining also brings roads, noise, and human settlements into previously inaccessible areas, increasing hunting pressure and reducing available habitat. In some parts of Peru, nearly 30% of the Mountain Tapir’s current range now overlaps with active or planned gold mining concessions (More et al., 2022).

Climate change pushing tapirs further uphill into shrinking habitat

As global temperatures rise, the high-elevation ecosystems where Mountain Tapirs live are shrinking. Suitable climate zones are shifting higher up the mountains, but because mountains have limited space at the top, this forces tapirs into ever smaller areas with fewer food resources. This phenomenon, known as “the escalator to extinction,” is especially dangerous for highland species like the Mountain Tapir, who cannot move downward into warmer zones. Climate change also alters rainfall patterns and vegetation cycles, further straining the species’ delicate habitat requirements.

Road construction and vehicle collisions within protected areas

Infrastructure development is rapidly cutting through mountainous areas, including roads that bisect national parks and reserves. This not only fragments tapir habitat but also leads to direct deaths through vehicle collisions. Once roads are completed, traffic speeds increase and tapirs crossing roads—especially at dawn and dusk—become highly vulnerable. Roads also make previously remote areas more accessible to poachers, settlers, and resource extractors, while local governments often lack sufficient ranger staff to monitor and protect these newly exposed areas.

Fumigation campaigns using toxic chemicals to eradicate drug crops

In Colombia, the government authorises aerial fumigation of coca and poppy fields using glyphosate-based herbicides like Round-Up. These chemicals are sprayed over wide areas, including forests and National Parks, contaminating soil, plants, and water sources. Mountain Tapirs can absorb these toxins through skin contact or ingestion, potentially leading to illness, reproductive failure, or death. Fumigation also destroys native plants that tapirs rely on for food, further decreasing habitat quality in affected areas.

Widespread introduction of cattle and the threat of disease transmission

Domestic cattle are increasingly being introduced into mountain tapir habitat, especially within protected areas where enforcement is weak. These animals not only compete with tapirs for forage but also carry diseases such as bovine tuberculosis and foot-and-mouth disease. Disease outbreaks have already been documented among tapirs in other parts of Latin America and pose a serious threat to small, isolated populations. In the Andes, cattle often form feral herds that reproduce and spread deep into cloud forests, further eroding habitat integrity and increasing the risk of tapir extinction.

Weak enforcement of environmental laws and lack of large protected areas in Peru

Although some Mountain Tapir habitat falls within designated protected areas, law enforcement in Peru is generally under-resourced and poorly coordinated. Rangers are too few to patrol vast mountainous regions effectively, and illegal activities such as mining, logging, and hunting continue within protected boundaries. Furthermore, most reserves are too small or fragmented to support viable tapir populations over the long term. Without stronger policies, larger protected zones, and meaningful binational cooperation with Ecuador and Colombia, tapirs in Peru face an uncertain future.

Low reproductive rate and slow population recovery

Mountain Tapirs have a long gestation period of around 13 months and typically produce only one calf at a time, meaning population growth is inherently slow. When combined with high mortality from hunting, roadkill, and disease, their populations cannot recover quickly from losses. Calves stay with their mothers for extended periods, further limiting reproductive output. This slow life cycle makes the species particularly vulnerable to sudden or sustained threats across their fragmented range.

Geographic Range

This species is found in the high Andes of Colombia, Ecuador, and northernmost Peru. In Colombia, they are present in the Central and Eastern Cordilleras but are absent from the Western Cordillera and Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta. In Ecuador, they range from the central Andes down through Sangay National Park to Podocarpus, with new records emerging from previously unconnected areas in the western Andes. In Peru, they occur north and south of the Huancabamba River in Cajamarca and Lambayeque (More et al., 2022). The total range in Peru is estimated at 183,000 hectares, but mining concessions cover nearly 30% of this habitat.

Diet

Mountain Tapirs are browsers, feeding on a wide variety of vegetation including leaves, shoots, fruits, and bromeliads. Their diet varies depending on the availability of plants within their high-altitude habitats, playing an important role as seed dispersers within these fragile ecosystems.

Mating and Reproduction

Mountain Tapirs have a slow reproductive rate, with a gestation period of approximately 13 months. Females typically give birth to a single calf, which stays with them for several months or even years before dispersing. Calves are born with white stripes and spots that fade as they mature. Their slow breeding cycle makes it difficult for populations to recover from hunting and habitat loss.

FAQs

How many Mountain Tapirs are left in the wild?

Fewer than 2,500 mature individuals remain in the wild, and the population is continuing to decline by at least 20% every two decades due to ongoing threats like habitat destruction, hunting, and climate change (IUCN, 2015).

What is the average lifespan of a Mountain Tapir?

In the wild, Mountain Tapirs may live up to 25 years, though this is significantly affected by environmental threats. Captive individuals can live slightly longer under safe and controlled conditions.

What are the biggest challenges to conserving Mountain Tapirs?

Major challenges include habitat fragmentation due to road construction, agriculture, and mining; the presence of armed conflict zones that hinder research and protection; and the slow reproduction rate of the species, which makes population recovery difficult (Guzmán-Valencia et al., 2024; More et al., 2022).

Do Mountain Tapirs make good pets?

No. Keeping a Mountain Tapir as a pet is unethical and illegal. These intelligent, solitary animals require large, wild habitats to survive. Capturing and trading them causes immense suffering and drives the species further toward extinction. Advocating against the exotic pet trade is vital to their survival.

Take Action!

Boycott palm oil and products linked to Andean deforestation. Support indigenous-led conservation and agroecology initiatives in the Andes. Call for stronger protections against mining and deforestation in Colombia, Ecuador, and Peru. Refuse to buy exotic animal products, including those used in folk medicine. #BoycottPalmOil #Boycott4Wildlife #Vegan #BoycottMeat

Support Mountain Tapirs by going vegan and boycotting palm oil in the supermarket, it’s the #Boycott4Wildlife

Support the conservation of this species

This animal has no protections in place. Read about other forgotten species here. Create art to support this forgotten animal or raise awareness about them by sharing this post and using the #Boycottpalmoil #Boycott4Wildlife hashtags on social media. Also you can boycott palm oil in the supermarket.

Further Information

Castellanos, A., Dadone, L., Ascanta, M., & Pukazhenthi, B. (2022). Andean tapir (Tapirus pinchaque) social groups and calf dispersal patterns in Ecuador. Boletín Técnico, Serie Zoológica, 17, 9–14. Retrieved from https://journal.espe.edu.ec/ojs/index.php/revista-serie-zoologica/article/view/2858

Delborgo Abra, F., Medici, P., Brenes-Mora, E., & Castelhanos, A. (2024). The Impact of Roads and Traffic on Tapir Species. In Tapirs of the World (pp. 157–165). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-65311-7_10

Guzmán-Valencia, C., Castrillón, L., Roncancio Duque, N., & Márquez, R. (2024). Co-Occurrence, Occupancy and Habitat Use of the Andean Bear and Mountain Tapir: Insights for Conservation Management in the Colombian Andes. SSRN. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.5061561

Lizcano, D.J., Amanzo, J., Castellanos, A., Tapia, A. & Lopez-Malaga, C.M. 2016. Tapirus pinchaque. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2016: e.T21473A45173922. https://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2016-1.RLTS.T21473A45173922.en. Accessed on 06 April 2025.

More, A., Devenish, C., Carrillo-Tavara, K., Piana, R. P., Lopez-Malaga, C., Vega-Guarderas, Z., & Nuñez-Cortez, E. (2022). Distribution and conservation status of the mountain tapir (Tapirus pinchaque) in Peru. Journal for Nature Conservation, 66, 126130. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jnc.2022.126130

How can I help the #Boycott4Wildlife?

Take Action in Five Ways

1. Join the #Boycott4Wildlife on social media and subscribe to stay in the loop: Share posts from this website to your own network on Twitter, Mastadon, Instagram, Facebook and Youtube using the hashtags #Boycottpalmoil #Boycott4Wildlife.

Enter your email address

Sign Up

Join 3,174 other subscribers2. Contribute stories: Academics, conservationists, scientists, indigenous rights advocates and animal rights advocates working to expose the corruption of the palm oil industry or to save animals can contribute stories to the website.

Wildlife Artist Juanchi Pérez

Mel Lumby: Dedicated Devotee to Borneo’s Living Beings

Anthropologist and Author Dr Sophie Chao

Health Physician Dr Evan Allen

The World’s Most Loved Cup: A Social, Ethical & Environmental History of Coffee by Aviary Doert

How do we stop the world’s ecosystems from going into a death spiral? A #SteadyState Economy

3. Supermarket sleuthing: Next time you’re in the supermarket, take photos of products containing palm oil. Share these to social media along with the hashtags to call out the greenwashing and ecocide of the brands who use palm oil. You can also take photos of palm oil free products and congratulate brands when they go palm oil free.

https://twitter.com/CuriousApe4/status/1526136783557529600?s=20

https://twitter.com/PhillDixon1/status/1749010345555788144?s=20

https://twitter.com/mugabe139/status/1678027567977078784?s=20

4. Take to the streets: Get in touch with Palm Oil Detectives to find out more.

5. Donate: Make a one-off or monthly donation to Palm Oil Detectives as a way of saying thank you and to help pay for ongoing running costs of the website and social media campaigns. Donate here

Pledge your supportLearn about other animals endangered by palm oil and other agriculture

GlobalSouth America S.E. AsiaIndiaAfricaWest Papua & PNG

Saola Pseudoryx nghetinhensis

Tucuxi Sotalia fluviatilis

Frill-Necked Lizard Chlamydosaurus kingii

Grey Crowned Crane Balearica regulorum

Ecuadorean Viscacha Lagidium ahuacaense

Southern Pudu Pudu puda

Learn about “sustainable” palm oil greenwashing

Read more about RSPO greenwashing

Lying Fake labelsIndigenous Land-grabbingHuman rights abusesDeforestation Human health hazardsA 2019 World Health Organisation (WHO) report into the palm oil industry and RSPO finds extensive greenwashing of palm oil deforestation and the murder of endangered animals (i.e. biodiversity loss)

Read more

#animals #Bantrophyhunting #Boycott4wildlife #BoycottGold #BoycottMeat #BoycottPalmOil #cattle #climateChange #climatechange #Colombia #deforestation #Ecuador #endangered #EndangeredSpecies #ForgottenAnimals #gold #herbivore #herbivores #hunting #infrastructure #lowlandTapir #Mammal #mammals #mining #PalmOil #palmOilDeforestation #palmoil #Peru #poaching #pollution #Tapir #Tapirs #ungulate #ungulates #vegan

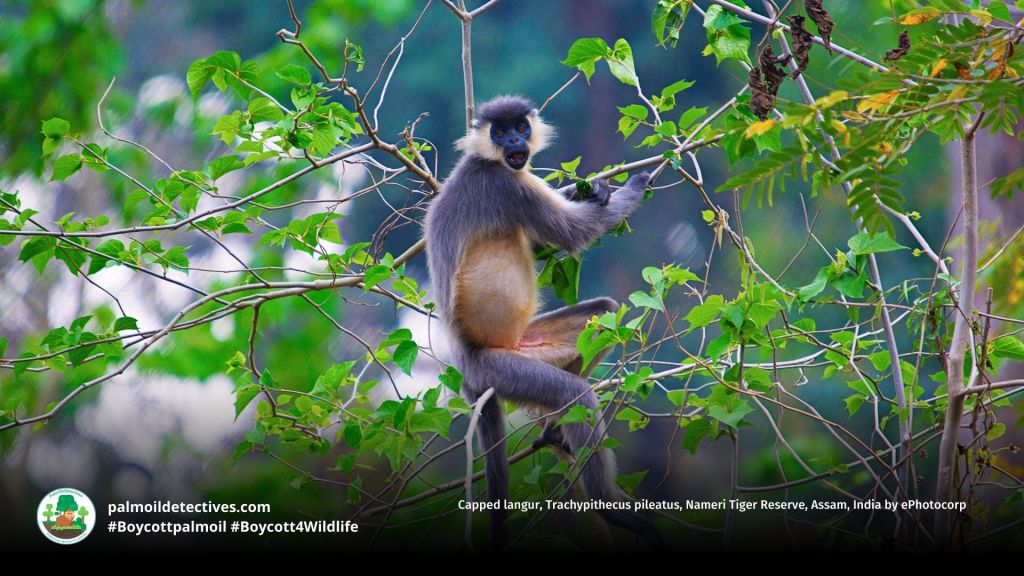

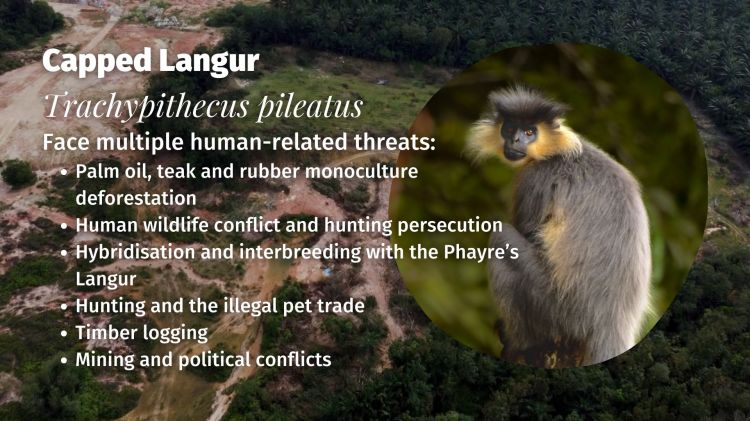

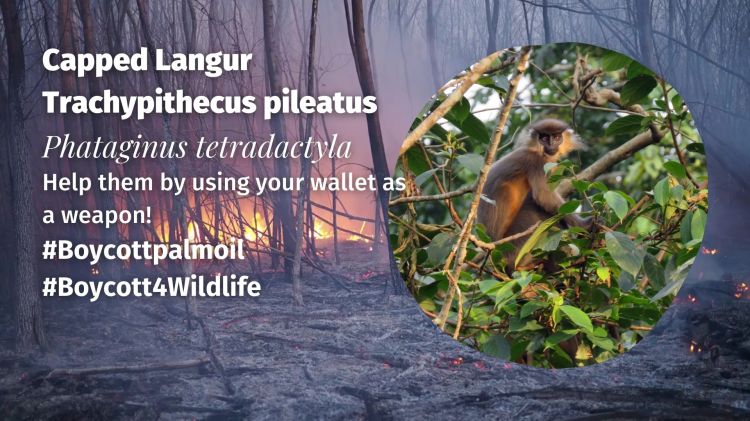

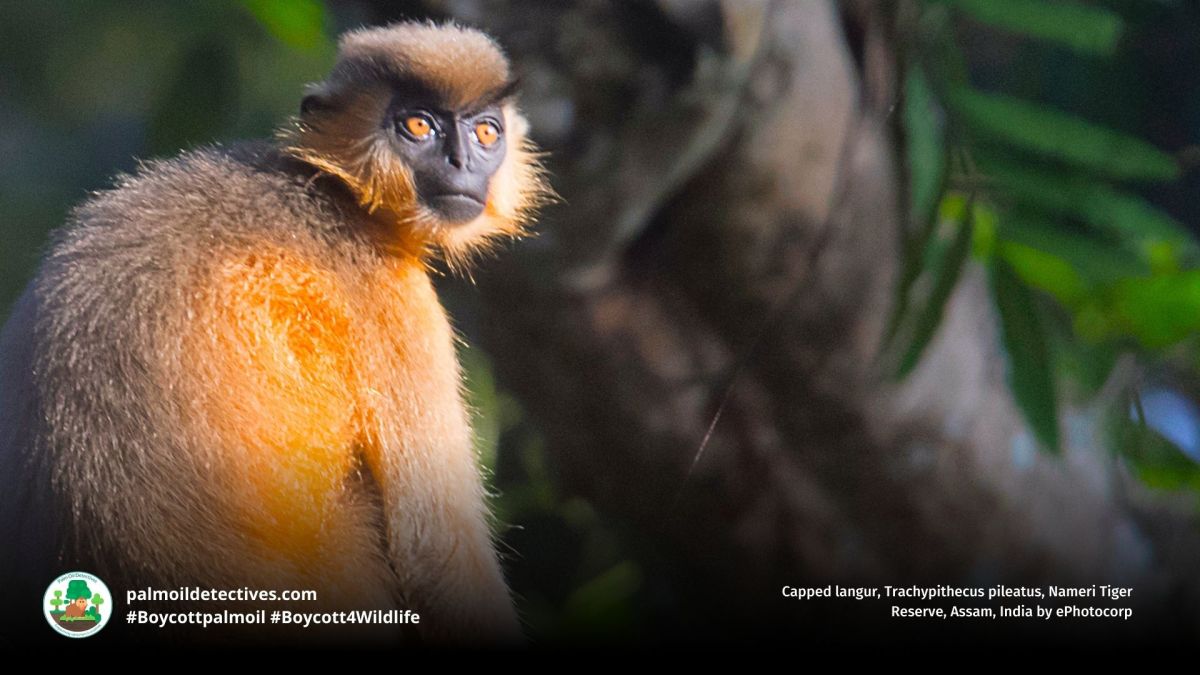

Capped Langur Trachypithecus pileatus

Capped Langur Trachypithecus pileatus

IUCN Red List Status: Vulnerable

Location: India, Bhutan, Bangladesh, Myanmar

This species inhabits subtropical and tropical dry forests, primarily in the foothills and highlands south of the Brahmaputra River and across fragmented patches in northeastern South Asia.

The capped #langur (Trachypithecus pileatus) is a graceful and beautiful leaf #monkey found across northeastern #India, #Bhutan, #Bangladesh, and #Myanmar. Sadly, they are listed as # Vulnerable on the IUCN Red List due to rapid population declines from #deforestation, logging, agriculture, and the devastating impacts of #palmoil plantations. Once widespread, their numbers have nearly halved in some regions like Assam due to the accelerating loss of native forest cover. Directly threatened by palm oil and monoculture expansion, this species is now confined to small, isolated forest fragments. Take action every time you shop and #BoycottPalmOil #Boycott4Wildlife

In the forests of #Bangladesh 🇧🇩 and northern #India 🇮🇳 lives a remarkable #primate with soulful hazel eyes 🐵🐒 on the verge of #extinction from #palmoil #deforestation. Help the Capped #Langur and #Boycottpalmoil 🌴🔥🚫 #Boycott4Wildlife @palmoildetect https://palmoildetectives.com/2026/01/11/capped-langur-trachypithecus-pileatus/

Share to BlueSky Share to TwitterThe intelligent and social Capped #Langur 🙉🐒🐵 is under pressure from #palmoil #deforestation and hunting in #India 🇮🇳 Troops are interbreeding with Phayre’s #langurs to survive. Fight for them and #Boycottpalmoil 🌴☠️❌ #Boycott4Wildlife @palmoildetect https://palmoildetectives.com/2026/01/11/capped-langur-trachypithecus-pileatus/

Share to BlueSky Share to TwitterAppearance & Behaviour

With their black-tufted crown, pale fur, and soulful eyes, capped langurs are among the most visually distinctive primates in the Eastern Himalayas. Their fur ranges from silver-grey to golden orange, with darker limbs and a black cap that gives them their name. They move gracefully through the canopy, rarely descending to the forest floor except for play or social grooming.

Capped langurs live in unimale, multifemale groups with sizes ranging from 8 to 15 individuals. They spend most of their time feeding (up to 67%) or resting (up to 40%), engaging in complex social grooming and vocal communication. Daily movements range from 320–800 metres across fragmented habitats of 21–64 hectares. Grooming is an important social activity, with females often taking turns in allomothering behaviour.

Threats

Palm oil, teak and rubber monoculture plantations

The spread of oil palm and other monoculture crops such as teak and rubber is destroying the capped langur’s native forests at an alarming rate. These industrial plantations eliminate the diverse tree species that capped langurs rely on for food and shelter, leaving them with little to survive on. Once a landscape is cleared and replaced with palm oil or other single crops, it becomes a green desert devoid of biodiversity, pushing the species closer to extinction. In regions like Assam and Bangladesh, palm oil is a major driver of habitat fragmentation and degradation, especially in forest corridors that once connected populations.

Timber deforestation

Widespread illegal logging, often fuelled by demand for timber and firewood, is rapidly eroding the capped langur’s habitat. Fruiting and lodging trees that are vital to their survival are cut down, leaving forests patchy and disconnected. As their home ranges shrink, capped langur groups are forced into smaller fragments, increasing their vulnerability to predators, food shortages, and inbreeding. In some areas, this pressure has led to local extinctions or the collapse of entire populations.

Slash-and-burn agriculture

Slash-and-burn agriculture destroys habitat for capped langurs and often brings them into closer contact with human settlements, increasing conflict and risk of hunting or roadkill. Forest recovery from this can take decades—time the capped langur simply doesn’t have.

Hunting and the illegal pet trade

Capped langurs are hunted for their meat, pelts, and for sale in the illegal pet trade. In many tribal and rural areas of Assam, Arunachal Pradesh, and Manipur, they are still targeted despite legal protections. Their pelts are used to make traditional knife sheaths, and infants are often captured after killing their mothers, then sold as pets. This exploitation causes severe suffering and has a devastating impact on group structures, leading to long-term population decline.

Roads cut into rainforests for mines and tea plantations

As forests are cut into smaller patches for roads, mining, tea plantations, and settlements, capped langur populations become increasingly isolated. Small, disconnected populations face higher risks of inbreeding, loss of genetic diversity, and eventual extinction. In some regions, such as Tinsukia and Sonitpur, populations have already disappeared due to this fragmentation. The collapse of corridors also disrupts daily movement, feeding patterns, and access to mates—placing enormous stress on surviving individuals.

Hybridisation with other species

Due to the rapid degradation of natural habitats, capped langurs are increasingly forming mixed-species groups with the closely related Phayre’s langur (Trachypithecus phayrei). Recent studies in northeast Bangladesh confirm genetically that hybridisation is occurring, which could result in the eventual cyto-nuclear extinction of the capped langur lineage. Although hybridisation can happen naturally, in this case it is being driven by human-induced fragmentation, forcing species into overlapping territories with fewer options for mates. This phenomenon is both a symptom and a driver of their decline, complicating conservation efforts.

Mining, infrastructure, and political conflict

Open-cast coal mining, limestone extraction, and petroleum exploration have all contributed to the destruction of capped langur habitat across Assam and Nagaland. Infrastructure projects, such as highways and border fences, not only destroy habitat directly but also block animal movements and isolate populations. In border regions, armed conflict and territorial skirmishes have already extirpated capped langurs from several reserves, such as the Nambhur and Rengma forests. Weak law enforcement allows habitat destruction to continue unchecked in many regions.

Geographic Range

Capped langurs are found in northeastern India (Arunachal Pradesh, Assam, Meghalaya, Nagaland, Manipur, Mizoram, and Tripura), Bhutan, northwestern Myanmar, and northeastern and central Bangladesh. They occur at elevations from 10 to 3,000 metres across hill forests, riverine reserves, and protected areas. However, their range is now severely fragmented by human development, with some populations disappearing from former strongholds due to mining, conflict, and agricultural encroachment.

Diet

Primarily folivorous, the capped langur’s diet includes mature and young leaves, petioles, seeds, flowers, bamboo shoots, bark, and occasionally caterpillars. They forage on more than 43 plant species, with favourites including banyan (Ficus benghalensis), sacred fig (Ficus religiosa), Terminalia bellerica, and Mallotus philippensis. Seasonal availability influences their feeding patterns, but they consistently prefer fruiting and flowering trees.

Mating and Reproduction

Breeding usually occurs in the dry season, with birthing concentrated between late December and May. The gestation period lasts about 200 days, and the interbirth interval is approximately two years. Only parous females participate in allomothering, allowing new mothers time to forage and recover, a behaviour rare among langurs and considered a form of altruism.

FAQs

How many capped langurs are left in the wild?

Exact numbers are uncertain, but estimates suggest the population in Assam has declined from 39,000 in 1989 to approximately 18,600 between 2008 and 2014 (Choudhury, 2014). This halving reflects habitat loss and increasing fragmentation, particularly in Upper Assam and the Barak Valley.

What is the average lifespan of a capped langur?

While data is limited, langurs of this genus generally live 20–25 years in the wild. Captive lifespans may extend slightly due to the absence of predators and constant food supply, though such conditions often lead to stress.

Why are capped langurs under threat?

Their decline is due to relentless deforestation, palm oil and monoculture plantations, illegal logging, and road-building. Slash-and-burn agriculture and mining also play a major role. Capped langurs are hunted in some regions for meat, pelts, and as pets, particularly in Assam, Arunachal Pradesh, and Nagaland.

Do capped langurs make good pets?

Absolutely not. Capped langurs are intelligent, social beings that rely on complex forest habitats and close-knit family groups. Removing them from the wild fuels extinction and causes immense trauma. Many die during illegal capture and transport. Keeping them as pets is a selfish act that destroys lives. If you care about capped langurs, never support the exotic pet trade!

What are the major conservation challenges for capped langurs?

The biggest issues are hybridisation with other primate species, habitat fragmentation, palm oil expansion, and human-wildlife conflict. The 2018 study in Satchari National Park found that local attitudes toward conservation vary by occupation, education, and gender, which means education and outreach are crucial. A big challenge is the rise in hybridisation with sympatric Phayre’s langurs, driven by habitat degradation—this poses long-term genetic risks (Ahmed et al., 2024).

Take Action!

Capped langurs are vanishing before our eyes, driven to the brink by out-of-control palm oil expansion, deforestation, and development. You can help save them.

Refuse to buy products made with palm oil. Support indigenous-led conservation in northeast India and the Eastern Himalayas. Demand governments halt the destruction of old-growth forests and restore wildlife corridors. Spread awareness and challenge the illegal wildlife trade. #BoycottPalmOil #Boycott4Wildlife #Vegan #BoycottMeat

Support the Capped Langur by going vegan and boycotting palm oil in the supermarket, it’s the #Boycott4Wildlife

Support the conservation of this species

This animal has no protections in place. Read about other forgotten species here. Create art to support this forgotten animal or raise awareness about them by sharing this post and using the #Boycottpalmoil #Boycott4Wildlife hashtags on social media. Also you can boycott palm oil in the supermarket.

Further Information

Ahmed, T., Hasan, S., Nath, S., Biswas, S., et al. (2024). Mixed-Species Groups and Genetically Confirmed Hybridization Between Sympatric Phayre’s Langur (Trachypithecus phayrei) and Capped Langur (T. pileatus) in Northeast Bangladesh. International Journal of Primatology, 46(1), 210–228. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10764-024-00459-x

Das, J., Chetry, D., Choudhury, A.U., & Bleisch, W. (2020). Trachypithecus pileatus (errata version published in 2021). The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2020: e.T22041A196580469. https://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2020-3.RLTS.T22041A196580469.en

Hasan, M.A.U., & Neha, S.A. (2018). Group size, composition and conservation challenges of capped langur (Trachypithecus pileatus) in Satchari National Park, Bangladesh. Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/339550399

Wikipedia. (n.d.). Capped langur. Retrieved April 6, 2025, from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Capped_langur

How can I help the #Boycott4Wildlife?

Take Action in Five Ways

1. Join the #Boycott4Wildlife on social media and subscribe to stay in the loop: Share posts from this website to your own network on Twitter, Mastadon, Instagram, Facebook and Youtube using the hashtags #Boycottpalmoil #Boycott4Wildlife.

Enter your email address

Sign Up

Join 3,173 other subscribers2. Contribute stories: Academics, conservationists, scientists, indigenous rights advocates and animal rights advocates working to expose the corruption of the palm oil industry or to save animals can contribute stories to the website.

Wildlife Artist Juanchi Pérez

Mel Lumby: Dedicated Devotee to Borneo’s Living Beings

Anthropologist and Author Dr Sophie Chao

Health Physician Dr Evan Allen

The World’s Most Loved Cup: A Social, Ethical & Environmental History of Coffee by Aviary Doert

How do we stop the world’s ecosystems from going into a death spiral? A #SteadyState Economy

3. Supermarket sleuthing: Next time you’re in the supermarket, take photos of products containing palm oil. Share these to social media along with the hashtags to call out the greenwashing and ecocide of the brands who use palm oil. You can also take photos of palm oil free products and congratulate brands when they go palm oil free.

https://twitter.com/CuriousApe4/status/1526136783557529600?s=20

https://twitter.com/PhillDixon1/status/1749010345555788144?s=20

https://twitter.com/mugabe139/status/1678027567977078784?s=20

4. Take to the streets: Get in touch with Palm Oil Detectives to find out more.

5. Donate: Make a one-off or monthly donation to Palm Oil Detectives as a way of saying thank you and to help pay for ongoing running costs of the website and social media campaigns. Donate here

Pledge your supportLearn about other animals endangered by palm oil and other agriculture

GlobalSouth America S.E. Asia IndiaAfricaWest Papua & PNG

Mountain Tapir Tapirus pinchaque

Saola Pseudoryx nghetinhensis

Tucuxi Sotalia fluviatilis

Frill-Necked Lizard Chlamydosaurus kingii

Grey Crowned Crane Balearica regulorum

Ecuadorean Viscacha Lagidium ahuacaense

Learn about “sustainable” palm oil greenwashing

Read more about RSPO greenwashing

Lying Fake labelsIndigenous Land-grabbingHuman rights abusesDeforestation Human health hazardsA 2019 World Health Organisation (WHO) report into the palm oil industry and RSPO finds extensive greenwashing of palm oil deforestation and the murder of endangered animals (i.e. biodiversity loss)

Read more

#animals #Assam #Bangladesh #Bantrophyhunting #Bhutan #Boycott4wildlife #BoycottMeat #BoycottPalmOil #CappedLangurTrachypithecusPileatus #deforestation #extinction #ForgottenAnimals #humanWildlifeConflict #hunting #illegalPetTrade #India #langur #Langurs #mining #monkey #monkeys #Myanmar #PalmOil #palmOilDeforestation #palmoil #PhayreSLeafMonkeyTrachypithecusPhayrei #poaching #Primate #vegan #vulnerable #VulnerableSpecies

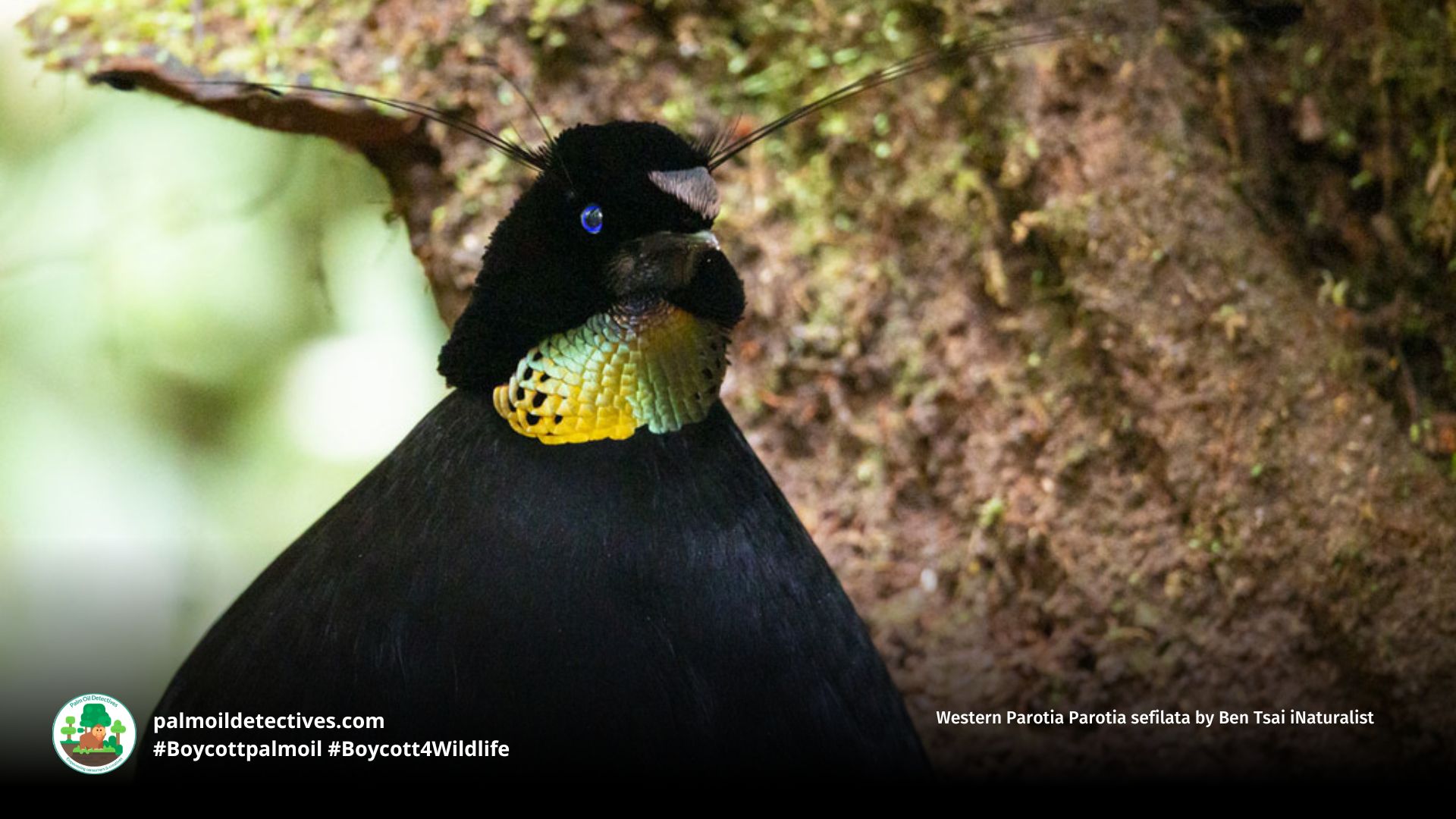

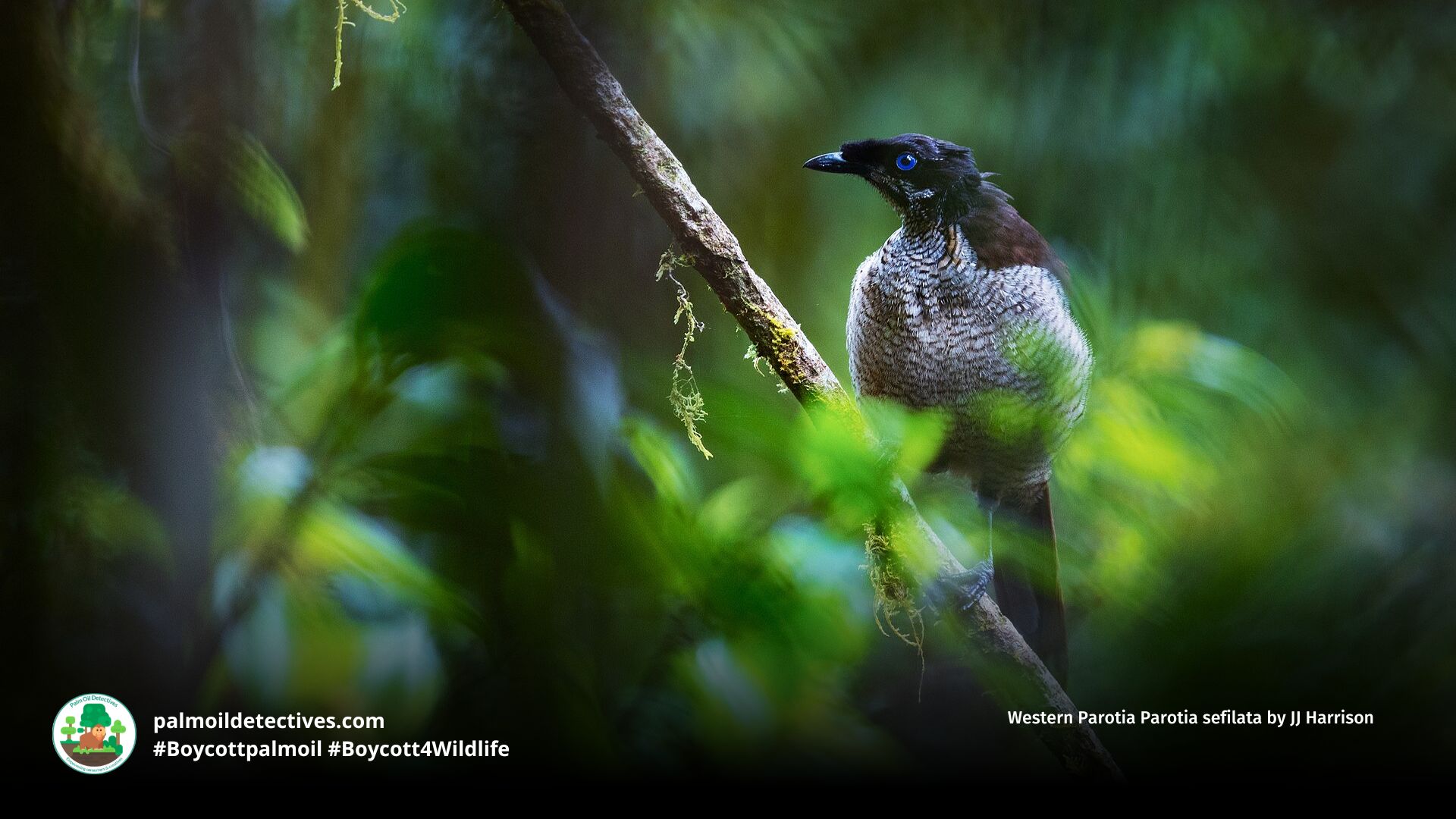

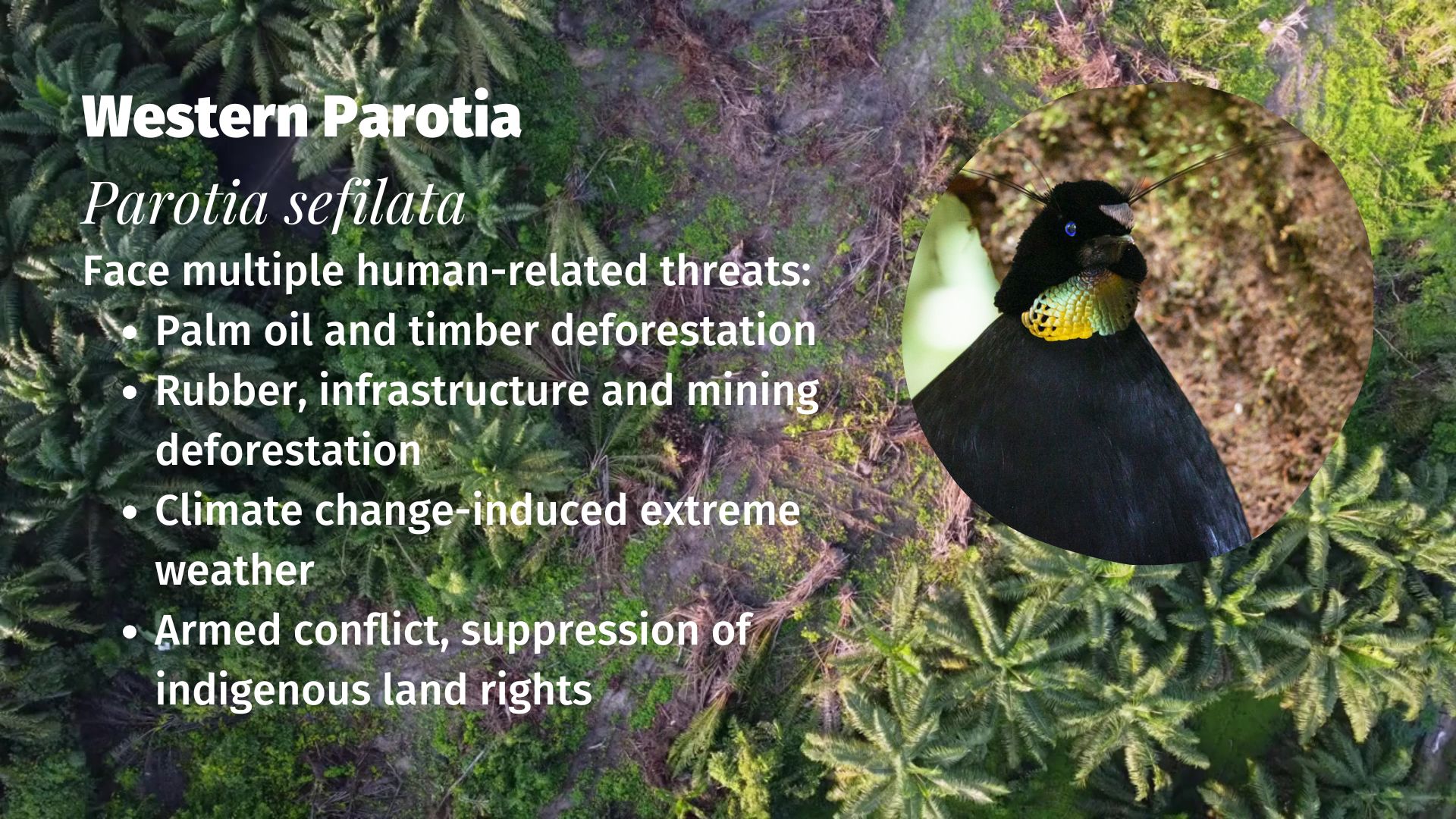

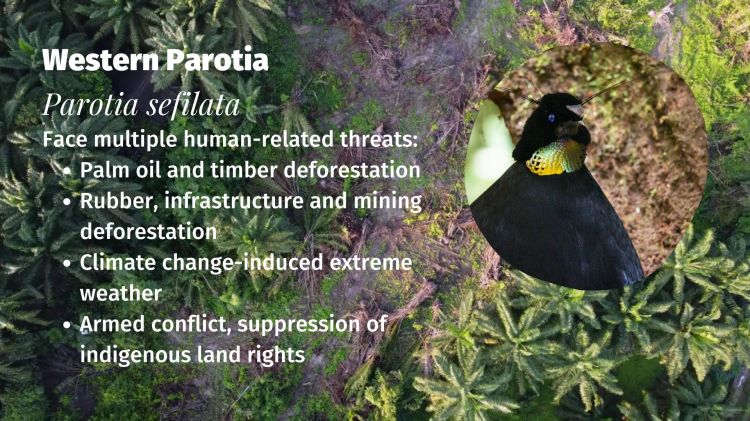

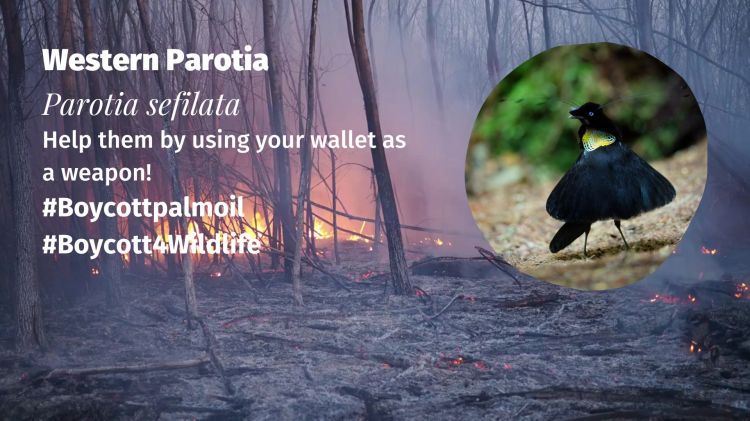

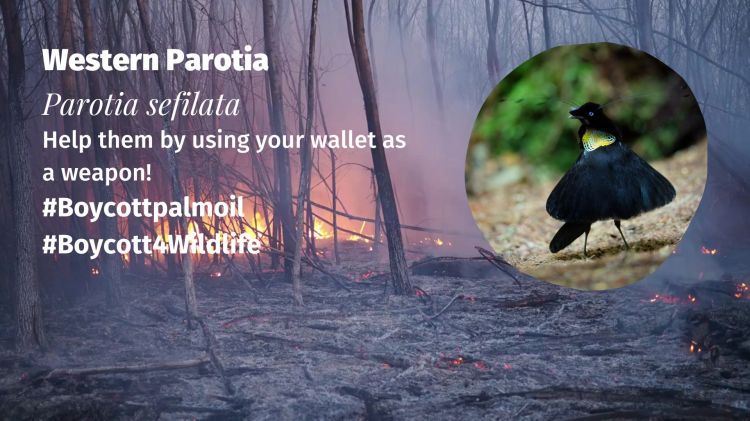

Western Parotia Parotia sefilata

Western Parotia Parotia sefilata

Location: West Papua (Illegally occupied by Indonesia)

Found exclusively in the montane forests of the Vogelkop Peninsula and Wandammen Mountains in Indonesian-occupied West Papua, this species is confined to isolated pockets of ancient, cloud-draped rainforest.

The Western Parotia Parotia sefilata, also called the Arfak Parotia, is a stunning bird-of-paradise of #WestPapua known for their mesmerising, ballerina-like courtship dance. Male #birds fan their iridescent flank plumes into a skirt and dazzle females with precise steps and shimmering throat shields. Although listed as Least Concern in 2016, this designation is dangerously outdated. The forests these rare birds call home have suffered catastrophic #deforestation in recent years due to the explosion of #palmoil plantations. These once-pristine regions are now fragmented and rapidly vanishing. Immediate action is needed to protect the Western Parotia from becoming the next victim of extinction.#BoycottPalmOil #Boycott4Wildlife

Unusual behaviours like mounting reveal complexity to the lives of Western #Parotia, thrilling #birds of paradise in #WestPapua. #Palmoil is a major threat. Fight for them and indigenous peoples #Boycottpalmoil #Boycott4Wildlife @palmoildetect https://palmoildetectives.com/2026/01/25/western-parotia-parotia-sefilata/

Share to BlueSky Share to TwitterWith jet black plumage 🖤 and bright green 💚 wattles, male Western Parotia #birds 🐦🦜🦚 of paradise gleam like scaly armour when they dance 🎶 Resist against their #extinction in #WestPapua when you #Boycottpalmoil 🌴🚫 #Boycott4Wildlife @palmoildetect https://palmoildetectives.com/2026/01/25/western-parotia-parotia-sefilata/

Share to BlueSky Share to TwitterAppearance & Behaviour

Male Western Parotias are instantly recognisable by their jet-black plumage, metallic green wattles that gleam like scaled armour, and three distinctive wire-like head plumes that curl outward from each side of the crown—features that inspired the species name, derived from the Latin sex filum, meaning ‘six threads.’ A dazzling inverted silver triangle on their head flashes during display, perfectly offset by their elegant black flank plumes which form a flared skirt in courtship. Females are more subdued, clad in streaky brown feathers, allowing them to blend into the forest understorey.

This species of bird-of-paradise is polygynous. Males gather in exploded leks—loosely spaced display grounds—where they clear leaf-littered forest floors to create courts. On these makeshift stages, they perform intricate displays to attract females, combining pirouettes, head bobs, feather shimmers, and rapid shakes. A 2024 behavioural study also observed rare alternative mating tactics, including homosexual mounting and sneak copulation attempts by female-plumaged birds, suggesting untapped behavioural complexity (MacGillavry et al., 2024).

Threats

The Western Parotia is officially listed as Least Concern, but this 2016 classification dangerously underrepresents their current reality. Since that assessment, massive deforestation for timber and palm oil has devastated much of their limited range, particularly across the Vogelkop Peninsula and Wandammen Mountains. The threats are mounting and accelerating due to the following drivers:

Palm oil deforestation

Large-scale clearing of primary rainforest to make way for industrial palm oil plantations is now rampant across the Bird’s Head (Vogelkop) Peninsula. Even remote montane forests where Western Parotias lek and nest are not safe, as new roads are cut to expand plantation frontiers.

Timber deforestation

Commercial timber extraction is removing centuries-old forest giants that the Western Parotia depends on for fruit, foraging and nesting. Logging roads also fragment habitat, increase fire risk, and provide access to previously undisturbed ecosystems.

Deforestation for mining, rubber and infrastructure projects

Government-backed agribusiness schemes are encouraging monocultures such as oil palm and rubber, which completely erase the forest understory and tree canopy vital for the Parotia’s food and shelter.

Mining concessions in West Papua—often enforced with military support—are rapidly opening up forests in the Wandammen Mountains, overlapping with the Parotia’s habitat. Road construction to access mines and plantations is fragmenting the landscape irreparably.

Climate change-induced extreme weather

The species is restricted to highland forest. As temperatures rise and human pressures encroach from below, their montane habitat may shrink to mountaintop fragments, leaving no room for retreat.

Colonial exploitation, military conflict and suppression of Indigenous land rights:

Indigenous Melanesians have stewarded Papuan forests for millennia. Today, state and corporate projects continue to override Indigenous consent, leading to ecological destruction and social injustice hand-in-hand.

These combined threats pose a serious and immediate danger to the survival of the Western Parotia. Without urgent action to halt deforestation and recognise Indigenous land sovereignty, the species could slide rapidly toward extinction unnoticed.

Geographic Range

Western Parotias are found exclusively in the montane and submontane rainforests of the Vogelkop Peninsula and the Wandammen Mountains in West Papua. They are forest specialists, requiring old-growth rainforest to support their complex courtship behaviour and nesting needs. Since their last assessment in 2016, widespread forest loss has occurred across these regions, particularly from illegal logging and palm oil expansion, putting their long-term survival in serious jeopardy.

Diet

Western Parotias primarily feed on fruits—especially figs—and supplement their diet with arthropods. Their foraging occurs at various forest levels, but they prefer mid-canopy and understorey, where fruiting trees and insect-rich foliage are abundant.

Mating and Reproduction

Courtship and nesting behaviour are marked by sexual division of labour. Only the female builds the nest and raises the chick. Nests are often camouflaged in dense foliage. Although the precise breeding season remains unclear, it is believed to vary by elevation and fruiting cycles. Male courtship is heavily influenced by evolutionary modularity in display traits, which have diverged over time, giving rise to the extravagant variety seen across the Parotia genus (Scholes, 2008).

FAQs

How many Western Parotias are left in the wild?

There are no exact population estimates for the Western Parotia. The IUCN has classified them as Least Concern, but this was based on assessments from 2016. Since then, vast tracts of their habitat have been lost. Without a recent survey, the current population trend is unknown, but it is likely decreasing due to ongoing deforestation (BirdLife International, 2016).

How long do Western Parotias live?

In the wild, birds-of-paradise often live between 5 to 10 years, though lifespan data for this species is limited. In captivity, related species have reached over 15 years, but no long-term studies exist for Parotia sefilata specifically.

What challenges do conservationists face protecting this species?

Conservation of the Western Parotia is complicated by a lack of recent data and the remoteness of their habitat. The Vogelkop and Wandammen regions are undergoing rapid transformation due to illegal logging and palm oil expansion, often facilitated by state-backed infrastructure projects. These forests also fall within contested indigenous lands, and conservation solutions must be rooted in indigenous sovereignty to be effective.

Is the Western Parotia affected by the exotic pet trade?

Unlike parrots and smaller songbirds, Western Parotias are not commonly targeted for the exotic pet trade, likely due to their remote habitat and specialised diet. However, increased accessibility due to road construction could change this. It is essential to remain vigilant and oppose any wildlife trafficking.

Take Action!

Use your wallet as a weapon to stop extinction by boycotting palm oil. Always choose products that are 100% palm oil-free to avoid contributing to the deforestation that is pushing the Western Parotia closer to extinction. Support indigenous-led conservation efforts in West Papua and call for greater transparency around the spread of monoculture plantations. Protect the mesmerising courtship rituals of these remarkable birds by fighting to keep their forests standing. #BoycottPalmOil #Boycott4Wildlife #Vegan #BoycottMeat

Support the Western Parotia by going vegan and boycotting palm oil in the supermarket, it’s the #Boycott4Wildlife

Support the conservation of this species

This animal has no protections in place. Read about other forgotten species here. Create art to support this forgotten animal or raise awareness about them by sharing this post and using the #Boycottpalmoil #Boycott4Wildlife hashtags on social media. Also you can boycott palm oil in the supermarket.

Further Information

BirdLife International. (2016). Parotia sefilata. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2016: e.T22706181A93913206. Retrieved 6 April 2025, from https://www.iucnredlist.org/species/22706181/93913206

MacGillavry, T., Janiczek, C., & Fusani, L. (2024). Video evidence of mountings by female-plumaged birds of paradise (Aves: Paradisaeidae) in the wild: Is there evidence of alternative mating tactics? Ethology. https://doi.org/10.1111/eth.13451

Scholes, E. (2008). Evolution of the courtship phenotype in the bird of paradise genus Parotia (Aves: Paradisaeidae): homology, phylogeny, and modularity. Biological Journal of the Linnean Society, 94(3), 491–504. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1095-8312.2008.01012.x

Wikipedia contributors. (n.d.). Western parotia. Wikipedia. Retrieved 6 April 2025, from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Western_parotia

How can I help the #Boycott4Wildlife?

Take Action in Five Ways

1. Join the #Boycott4Wildlife on social media and subscribe to stay in the loop: Share posts from this website to your own network on Twitter, Mastadon, Instagram, Facebook and Youtube using the hashtags #Boycottpalmoil #Boycott4Wildlife.

Enter your email address

Sign Up

Join 3,176 other subscribers2. Contribute stories: Academics, conservationists, scientists, indigenous rights advocates and animal rights advocates working to expose the corruption of the palm oil industry or to save animals can contribute stories to the website.

Wildlife Artist Juanchi Pérez

Mel Lumby: Dedicated Devotee to Borneo’s Living Beings

Anthropologist and Author Dr Sophie Chao

Health Physician Dr Evan Allen

The World’s Most Loved Cup: A Social, Ethical & Environmental History of Coffee by Aviary Doert

How do we stop the world’s ecosystems from going into a death spiral? A #SteadyState Economy

3. Supermarket sleuthing: Next time you’re in the supermarket, take photos of products containing palm oil. Share these to social media along with the hashtags to call out the greenwashing and ecocide of the brands who use palm oil. You can also take photos of palm oil free products and congratulate brands when they go palm oil free.

https://twitter.com/CuriousApe4/status/1526136783557529600?s=20

https://twitter.com/PhillDixon1/status/1749010345555788144?s=20

https://twitter.com/mugabe139/status/1678027567977078784?s=20

4. Take to the streets: Get in touch with Palm Oil Detectives to find out more.

5. Donate: Make a one-off or monthly donation to Palm Oil Detectives as a way of saying thank you and to help pay for ongoing running costs of the website and social media campaigns. Donate here

Pledge your supportLearn about other animals endangered by palm oil and other agriculture

GlobalSouth America S.E. AsiaIndiaAfricaWest Papua & PNG

Capped Langur Trachypithecus pileatus

Mountain Tapir Tapirus pinchaque

Saola Pseudoryx nghetinhensis

Tucuxi Sotalia fluviatilis

Frill-Necked Lizard Chlamydosaurus kingii

Grey Crowned Crane Balearica regulorum

Learn about “sustainable” palm oil greenwashing

Read more about RSPO greenwashing

Lying Fake labelsIndigenous Land-grabbingHuman rights abusesDeforestation Human health hazardsA 2019 World Health Organisation (WHO) report into the palm oil industry and RSPO finds extensive greenwashing of palm oil deforestation and the murder of endangered animals (i.e. biodiversity loss)

Read more

#animals #Bird #birds #Birdsong #Boycott4wildlife #BoycottMeat #BoycottPalmOil #deforestation #EndSongbirdTrade #extinction #ForgottenAnimals #FreeWestPapua #gold #goldMining #hunting #indigenous #military #PalmOil #palmOilDeforestation #palmoil #Parotia #poaching #songbird #songbirds #vegan #vulnerable #VulnerableSpecies #WestPapua #WesternParotiaParotiaSefilata #WestPapua

South America: Species Endangered by Palm Oil Deforestation

Papua New Guinea & West Papua: Species Endangered by Palm Oil Deforestation

Palm Oil Lobbyists Getting Caught Lying Orangutan Land Trust and Agropalma

Animal agriculture and meat, The contents of your fridge and dining table directly impacts the future of rare rainforest and ocean animals. That’s because industrial agriculture and aquaculture for commodities like meat, dairy, fish and palm oil is driving animals in the most biodiverse ecosystems on the planet closer towards extinction.

Animal agriculture and meat, The contents of your fridge and dining table directly impacts the future of rare rainforest and ocean animals. That’s because industrial agriculture and aquaculture for commodities like meat, dairy, fish and palm oil is driving animals in the most biodiverse ecosystems on the planet closer towards extinction.

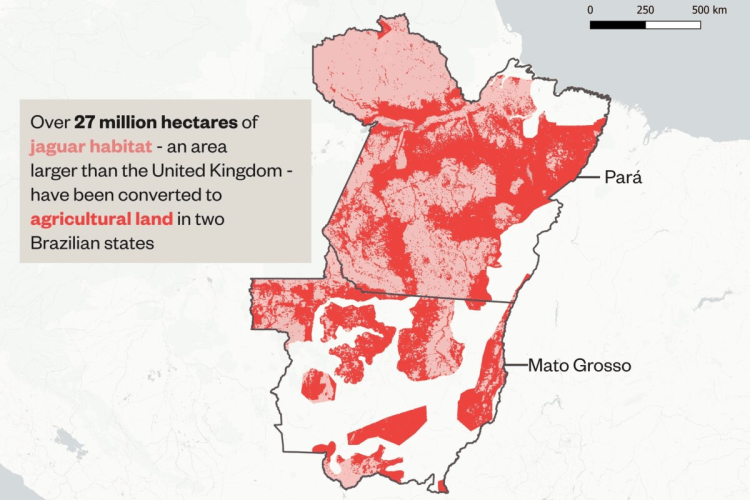

A road in Brazil which drives deep into jaguar habitat. Ricardo de O. Lemos/Shutterstock

A road in Brazil which drives deep into jaguar habitat. Ricardo de O. Lemos/Shutterstock Jaguar Panthera onca by Ecuadorian artist Juanchi Pérez

Jaguar Panthera onca by Ecuadorian artist Juanchi Pérez A jaguar in the jungle of southern Mexico. Mardoz/Shutterstock

A jaguar in the jungle of southern Mexico. Mardoz/Shutterstock