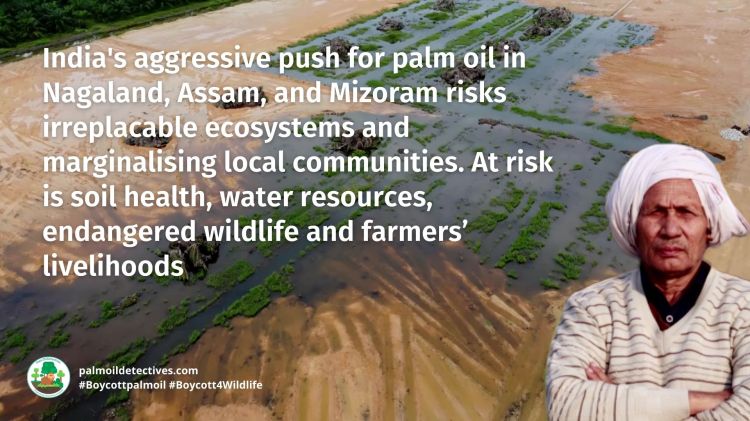

India’s Palm Oil Plans Wreak Havoc On The Ground

#India’s aggressive push for #palmoil plantations in #Nagaland, #Assam and #Mizoram is wreaking havoc on both the environment and local communities. The government plans to ramp up oil palm cultivation in the northeast, locking away land that could be used for diverse food production for decades. Palm oil monoculture threatens soil health, drains precious water resources, and marginalises indigenous communities. Farmers in the north east of India are facing dire challenges, from delayed subsidies to inadequate payments for their crops, leaving them questioning the viability of oil palm farming. A rethink is necessary to protect India’s ecosystems, animals and people. To help raise awareness and empower change, make sure that you #BoycottPalmOil #Boycott4Wildlife every time you shop.

In #Nagaland and #Mizoram, #India 🇮🇳 an ongoing battle is raging for #farmers’ rights to feed their families and not suffer penniless for #palmoil in a barren wasteland #Boycottpalmoil 🌴🪔🚫 #Boycott4Wildlife #humanrights @palmoildetect https://palmoildetectives.com/2024/10/06/indias-palm-oil-plans-wreak-havoc-on-the-ground/

Share to BlueSky Share to TwitterIn lush North East #India 🇮🇳🪷 a battle is being waged, between sowing native seeds versus industrial #palmoil #monoculture 🌴🔥 that threatens rare #ecosystems #animals and an ancient way of life. #ecology #Boycottpalmoil #Boycott4Wildlife @palmoildetect https://palmoildetectives.com/2024/10/06/indias-palm-oil-plans-wreak-havoc-on-the-ground/

Share to BlueSky Share to TwitterOriginally published under Creative Commons by 360info on August 12, 2024. Written by Dr Ravi Chellam is a wildlife biologist and conservation scientist based in Bengaluru along with senior journalist Rupa Chinai and Robert Solo is a member of the Naga civil society organisation, Kezekevi Thehou Ba (KTB) which works with communities, the government and the civil society in Nagaland. Read the original article.

The push for large-scale monoculture plantations like palm oil in India is taking a heavy toll on the environment and on people’s economic and social security.

Oil palm plantations lock in precious land resources for a long time, from a 4-5 year gestation period to 25 years for production, a problem in a densely populated country like India.

In late July, an unusual newspaper headline did the rounds: “If India gives land, we will work together to produce palm oil here, says visiting Malaysian Minister.”

Foreign politicians do not often ask the country they are visiting to give land, in particular for cultivating a plant which produces oil seeds.

In this case, the seeds refer to the oil palm, a species native to West Africa and now widely cultivated, especially in Southeast Asia. Oil palm is seen as the world’s most important oil crop, supplying approximately 40 percent of global demand for vegetable oil.

Clearly, the pressure is building on big palm oil-producing countries such as Malaysia and Indonesia to clean up their act.

The European Union has taken a strong stance on cleaning up supply chains to prevent deforestation, environmental degradation and negative impacts on local communities.

India is the world’s largest importer of edible oils but this was not always the case.

Indians have traditionally used a wide variety of edible oils, a reflection of India’s rich agro-ecological heritage and cultural diversity. In the early 1990s, India was self-sufficient in edible oils but thanks to changes in government policies, that situation has reversed.

Palm oil now dominates India’s edible oil imports, representing more than half of all edible oil imports. In 2021, palm oil import was valued at approximately $US8.63 billion.

Indian Rhino in Assam, India by Craig Jones Wildlife Photography

Indian Rhino in Assam, India by Craig Jones Wildlife PhotographyDue to this significant dependence on imports, there has been a strong push by the Indian government to rapidly increase the cultivation of oil palm, especially in India’s northeast, through the National Mission on Edible Oils — Oil Palm.

It has set ambitious goals to increase the area of oil palm cultivation in India to one million hectares by 2025-26 from 350,000ha in 2019-20.

However, the government’s efforts in promoting oil palm plantations in the northeast, which are strengthened by substantial subsidies, are playing havoc with tribal society.

Land is a scarce resource in the northeast and existing land, often community-owned and managed, has traditionally been used for subsistence farming with an eye on food security. This is changing and creating social disruption.

Challenges of growing oil palm

More than 50 percent of the proposed increase in the area of cultivation, 328,000ha, is planned in the northeastern states, as identified in an assessment by the Indian Institute of Oil Palm Research in 2020.

The plan is also to increase the production of crude palm oil from 27,000 tonnes in 2019-20 to 1.12 million tonnes by 2025-26.

While the ambition and goals of the oil palm mission are lofty, the on-the-ground situation in the northeast tells a completely different story.

Mizoram was the first state to start planting oil palm in the northeast. Plantations were established in seven districts of the state and at least some of these date back to 2005.

Over the last two decades, oil palm plantations have invariably resulted in setbacks and failures for everyone involved.

Given their intrinsically high requirements of water and nutrients, oil palm plantations have devastated soil health and the quality and availability of groundwater in the state.

Animals and Ecosystems at Risk in India

Rivers are still people in South East Asia despite court showdown

Healthy rivers are essential for community wellbeing. India and Bangladesh legally recognise rivers as natural persons with rights and powers. Take action!

Protecting India’s Tigers Saves One Million Tonnes of CO2

#India’s fifty year long Project #Tiger has been a successful conservation project. A new research study finds that protecting tigers and their rainforest home has additional benefits to #carbonemissions, saving 1 million tonnes of CO2 from being spewed into the atmosphere. Conserving tigers as an iconic and legendary species is deeply ingrained into the world’s…

Concerns Mount Over Palm Oil Expansion in Nagaland

The NCCAF raises grave concerns over palm oil expansion in Nagaland, India with threats to deforestation, biodiversity, livelihoods. Take action!

Load more posts

Something went wrong. Please refresh the page and/or try again.

Sloth Bear Melursus ursinus

The sloth bear (Melursus ursinus), with their distinctive “Y” or “V” shaped chest patch and shaggy fur, are unique bears native to the Indian subcontinent. Once exploited as ‘dancing bears’ by the Kalandar tribe, this phase of history is thankfully now over. They now roam across tropical forests and savannahs while snuffling through termite mounds…

Nicobar Long-Tailed Macaque Macaca fascicularis umbrosa

Discover the intriguing Nicobar long-tailed macaque, intelligent and highly social survivors on India’s islands, help them to survive and boycott palm oil!

Phayre’s Leaf Monkey Trachypithecus phayrei

Phayre’s leaf monkey, also known as Phayre’s langur, are remarkable Old World monkeys distinguished by large, white-rimmed eyes that lend them a “spectacled” appearance. Known locally as ‘Chasma bandor’ they live mostly in the lush forests of India, Bangladesh and Myanmar. Major threats to their survival include habitat destruction from palm oil and rubber plantations,…

Load more posts

Something went wrong. Please refresh the page and/or try again.

Irrawaddy Dolphin Orcaella brevirostris

Intelligent and social Irrawaddy dolphins, also known as the Mahakam River dolphins or Ayeyarwady river #dolphins have endearing faces. Only 90 to 300 are estimated to be left living in the wild. Their rounded and expressive looking noses liken them to a baby beluga whale or the Snubfin dolphin of Australia. These shy #cetaceans are…

Sambar deer Rusa unicolor

The majestic Sambar deer, cloaked in hues ranging from light brown to dark gray, are distinguished by their rugged antlers and uniquely long tails. Adorned with a coat of coarse hair and marked by a distinctive, blood-red glandular spot on their throats, these deer embody the beauty of the wild. Their adaptability is evident in…

Lion-tailed Macaque Macaca silenus

Lion-tailed macaques hold the title of one of the smallest macaque species in the world and sport a majestic lion-esque mane of hair. They exclusively call the Western Ghats in India their home. This area has been decimated in recent years for palm oil. Prior to palm oil’s arrival in the Western Ghats, populations of…

Load more posts

Something went wrong. Please refresh the page and/or try again.

Another issue is the long gestation period of the crop. The oil palm takes at least four to five years before it starts producing fruit, followed by a productive period of 20 to 25 years.

This adds up to 25 to 30 years, a long time to lock in precious land resources, especially in a densely populated country such as India.

The challenges with environmental sustainability, productivity, transport, failings of the government and corporate behaviour have meant that both farmers and the companies have had to deal with large-scale failures and heavy losses.

The rugged terrain and remote location of the plantations, coupled with the relatively poor road network and the absence of oil mills close to many of the plantations poses severe challenges to the farmers.

The nuts have to be processed within 48 hours, which currently is a logistical nightmare, especially for many small-scale farmers.

Many companies haven’t honoured their commitments to farmers be it on purchase price or timely payments. Government subsidies have also been often delayed.

The land question

Land is the central issue for the palm oil enterprise.

Be it terrain, with hilly terrain not being suitable for oil palm plantations; rapidly depleting soil fertility or reduced access to land owned by small landholders because of the three decade lock-in period.

In several cases, people have had to sell their land due to the extensive financial losses they’ve suffered while cultivating oil palm.

The capture of common lands for planting oil palm by the elite of the society is a large-scale problem, especially in Arunachal Pradesh, another northeastern state.

The fear is that more and more of community land will get converted into at least de facto private property when planted with oil palm due to the decades-long lock-in period.

This dispossession is likely to result in further marginalisation of the poorer sections of society and could potentially lead to social turmoil and conflict.

The problems are many and widespread.

Farmers across the northeast are not readily taking up planting of oil palm as they have started to realise the environmental costs, the meagre and very often delayed economic returns and the three-decade-long lock-in period of their land.

Sikkim and Meghalaya have decided to stay away from planting oil palm.

A recent report seems to indicate that at least some farmers in Arunachal Pradesh are starting to gain benefits from their oil palm plantations. These are still very early days to reach any definite conclusion about the situation in Arunachal, unlike the much longer Mizoram experience.

Since January 2023, researchers have engaged with tribal elders and civil society members in Nagaland which has provided them a close view of how things are playing out for oil palm in the state.

Nagaland seems to be following a similar path to Arunachal Pradesh, with the wealthy consolidating landholdings to establish plantations, resulting in small landholders losing out.

It is clear that oil palm is a capital-intensive and very long-term crop. Deep pockets are required to survive and succeed.

Almost everyone researchers interacted with expressed their disappointment at the delays, reduction or even complete stoppage of payment of the committed government subsidies.

Farmer frustrations

Farmers’ experiences in dealing with private companies that had committed to buy oil palm fruit has been an even greater disappointment.

The purchase price for these bunches is much lower than what was initially indicated and payments are unduly delayed.

Even the picking up of fresh fruit bunches, a perishable commodity which has to be processed within 24 to 48 hours post-harvesting, is poorly coordinated and there is a lack of reliable information and guidance for farmers.

The environmental and social issues associated with oil palm plantations are also playing out in Nagaland, including depleting soils, water shortages, the increasing use of hazardous agro-chemicals, rapidly increasing labour costs, women losing out on employment opportunities and shifts in land tenure and ownership.

Recent fieldwork in Nagaland through meetings and conversations with farmers presents a mixed picture.

Several farmers confirmed their fresh fruit bunches have not been picked up by companies. They believe it might have something to do with the company’s assessment of the quality of the fruit.

This is not in line with the commitment that was made to these farmers and is resulting in tremendous losses for them.

A few others are receiving the government subsidies and their fresh fruit bunches have also been picked up by the companies and they have been paid Rs13 a kilogram, approximately $USD 0.16.

Course correction

The longer-term experience with oil palm hasn’t been good for farmers in India’s northeast both from financial and social perspectives.

When also considering the environmental impacts, it is clear that the push for large-scale cultivation of oil palm in the region is taking a toll on the environment as well on people’s economic and social security.

Government policy would benefit from encouraging local and ecologically-appropriate oil-bearing crops rather than massively supporting oil palm.

Even the government’s own estimates do not predict India gaining self-sufficiency in edible oil by cultivating oil palm in India.

Rethinking this policy may be required so that India can regain self-sufficiency in edible oils, a position we enjoyed not so long ago.

Originally published under Creative Commons by 360info on August 12, 2024. Written by Dr Ravi Chellam is a wildlife biologist and conservation scientist based in Bengaluru along with senior journalist Rupa Chinai and Robert Solo is a member of the Naga civil society organisation, Kezekevi Thehou Ba (KTB) which works with communities, the government and the civil society in Nagaland. Read the original article.

ENDS

Read more about deforestation and ecocide in the palm oil industry

Finance giants fuel $8.9 trillion deforestation economy

Forest 500 report shows 150 of the world’s largest financial institutions invested nearly $9 trillion in deforestation-linked industries. Support EUDR!

The Indigenous Malaysian concept of ‘Badi’: respecting the land and wildlife

The Indigenous Semai #indigenous people of #Malaysia can teach us a lot about how to protect people, planet and biodiversity. The Indigenous concept of #badi is not superstition or taboo, it’s about respecting…

Family Ties Expose Deforestation and Rights Violations in Indonesian Palm Oil

An explosive report by the Environment Investigation Agency (EIA) details how Indonesia’s Fangiono family, through a wide corporate web, is linked to ongoing #deforestation, #corruption, and #indigenousrights abuses for #palmoil. Calls mount for…

Deforestation Devastates Tesso Nilo National Park’s Endangered Creatures

Act now to save Tesso Nilo Park. This vital Indonesian park has lost 78% of its primary forest, threatening the habitat of Sumatran tigers and elephants

Deforestation Shifts Tree Species in Brazilian Forests

Deforestation in Brazilian forests causes shift towards fast-growing, small-seeded trees, threatening biodiversity, carbon storage. Take action!

Load more posts

Something went wrong. Please refresh the page and/or try again.

Take Action in Five Ways

1. Join the #Boycott4Wildlife on social media and subscribe to stay in the loop: Share posts from this website to your own network on Twitter, Mastadon, Instagram, Facebook and Youtube using the hashtags #Boycottpalmoil #Boycott4Wildlife.

Enter your email address

Sign Up

Join 3,172 other subscribers2. Contribute stories: Academics, conservationists, scientists, indigenous rights advocates and animal rights advocates working to expose the corruption of the palm oil industry or to save animals can contribute stories to the website.

Wildlife Artist Juanchi Pérez

Mel Lumby: Dedicated Devotee to Borneo’s Living Beings

Anthropologist and Author Dr Sophie Chao

Health Physician Dr Evan Allen

The World’s Most Loved Cup: A Social, Ethical & Environmental History of Coffee by Aviary Doert

How do we stop the world’s ecosystems from going into a death spiral? A #SteadyState Economy

3. Supermarket sleuthing: Next time you’re in the supermarket, take photos of products containing palm oil. Share these to social media along with the hashtags to call out the greenwashing and ecocide of the brands who use palm oil. You can also take photos of palm oil free products and congratulate brands when they go palm oil free.

https://twitter.com/CuriousApe4/status/1526136783557529600?s=20

https://twitter.com/PhillDixon1/status/1749010345555788144?s=20

https://twitter.com/mugabe139/status/1678027567977078784?s=20

4. Take to the streets: Get in touch with Palm Oil Detectives to find out more.

5. Donate: Make a one-off or monthly donation to Palm Oil Detectives as a way of saying thank you and to help pay for ongoing running costs of the website and social media campaigns. Donate here

Pledge your support#animals #Assam #BoycottPalmOil #Boycott4wildlife #BoycottPalmOil #corruption #deforestation #ecology #ecosystems #farmers #humanRights #HumanRights #hunger #India #Mizoram #monoculture #Nagaland #PalmOil #palmOilDeforestation #palmoil #poverty #workersRights #WorkersRights

Unsupported type or deleted object

Ecuadorean Viscacha Lagidium ahuacaense

Ecuadorean Viscacha Lagidium ahuacaense

IUCN Status: Critically Endangered

Location: Ecuador’s Cerro El Ahuaca

High in the remote granite outcrops of Cerro El Ahuaca, #Ecuador the Ecuadorean #Viscacha Lagidium ahuacaense is plump and fluffy #rodent sporting sage-like long whiskers. From their high perch they look down upon the world below with a permanent expression of what could interpreted as disappointment. Ecuadorean Viscachas were first spotted in 2005 and formally described in 2009, these mountain-dwelling large #rodents are the northernmost member of the Lagidium genus, marooned over 500 kilometres from their closest relatives in #Peru. Few creatures are as elusive or fascinating— tragically, only a handful of them remain alive.

Fires, #beef agriculture, and #deforestation for monoculture are carving away at their already fragile existence, pushing them ever closer to the brink of #extinction. Help them by sharing their story to social media. Join the #Boycott4Wildlife.

High in the mountains of #Ecuador 🇪🇨 lives a sage-like fluffy #rodent, the Ecuadorean #Viscacha, a critically endangered alpine wonder. Few remain alive due to #climatechange and #meat #agriculture 🥩🔥. Be #vegan for them #Boycott4Wildlife @palmoildetect https://wp.me/pcFhgU-aoV

Share to BlueSky Share to TwitterThe Ecuadorean #Viscacha is a fluffy epic #rodent of #Ecuador’s high mountains with long and wise whiskers and a bushy tail. These tenacious creatures are critically #endangered 😭😿 Help them to survive, be #vegan #Boycott4Wildlife 🥩🔥⛔️ @palmoildetect https://wp.me/pcFhgU-aoV

Share to BlueSky Share to TwitterAppearance & Behaviour

Built for survival in one of Ecuador’s harshest landscapes, the Ecuadorean Viscacha is a sturdy and big rodent with a compact body covered in thick, grey-brown fur. Their dense, woolly fur shields them from the biting Andean winds, while their long, silvery tails provide balance as they scale sheer rock faces. Their large, dark eyes scan the terrain for danger, and their long, sensitive whiskers twitch as they pick up the faintest vibrations in the wind.

Long and distinguished whiskers provide them with sensitive and deep understanding of their environment. A black dorsal stripe runs the length of their back, this disappears into the dense coat that keeps them warm against the mountain’s chill.

Most active at dawn and dusk, their every movement is deliberate. They bound effortlessly between jagged outcrops, using their powerful hind legs to launch themselves across treacherous gaps. Unlike burrowing rodents, they take refuge in narrow rock crevices, where they remain hidden from predators.

Threats

Once secure in their isolated stronghold, the Ecuadorean Viscacha now faces a gauntlet of human-driven threats. Their already tiny population is being squeezed into an ever-smaller fragment of land, where survival is becoming increasingly precarious.

Deforestation for eucalyptus and pine monoculture plantations

For generations, wildfires have been used to clear land for agriculture and livestock grazing, but in recent decades, these fires have intensified, spreading further into the Viscacha’s habitat. Each blaze devours critical vegetation, stripping away the food sources they rely on and forcing them into ever-smaller pockets of surviving habitat.

Farmed Animal Agriculture

Grazing cattle have become an unrelenting force in the region, trampling vegetation and outcompeting the Viscacha for food. Their presence has disrupted the delicate balance of this fragile ecosystem, leaving fewer resources for native wildlife.

Climate Change-related Environmental Shifts

With their entire known population confined to a single mountain, the Ecuadorean Viscacha is especially vulnerable to even the smallest environmental shifts. Changing rainfall patterns, prolonged droughts, and temperature fluctuations could alter the availability of food and water, placing further stress on their already limited numbers.

Population Fragmentation and Isolation

Trapped within a tiny range with no known neighbouring populations, the Viscacha is cut off from potential mates and genetic diversity. Without intervention, this isolation could lead to inbreeding, weakening the species’ ability to adapt and survive.

Geographic Range

The Ecuadorean Viscacha is found only in a single location—Cerro El Ahuaca, a rugged granite mountain in southern Ecuador. They inhabit steep, rocky surfaces at elevations between 1,950 and 2,480 metres, a world of exposed rock faces and sparse vegetation. No other known populations exist, making them one of the most geographically restricted mammals on the planet.

Though their habitat once stretched further, fires and deforestation have steadily chipped away at the fringes of their territory. Today, their entire known range spans just 120 hectares—an area smaller than many urban parks—leaving them with little room to escape the pressures of a changing world.

Diet

These high-altitude specialists are herbivores, feeding primarily on native grasses, shrubs, and small herbs that cling to the mountainside. Signs of their feeding are visible throughout their habitat—freshly grazed plants and stripped vegetation mark the places where they have foraged. Their diet is shaped by scarcity, forcing them to survive on whatever plant life they can find in their isolated, rocky home. Their close relatives Mountain Viscacha of Peru are preyed upon by Andean Mountain Cats.

Mating and Reproduction

Little is known about the reproductive habits of the Ecuadorean Viscacha, but they likely follow a pattern similar to their relatives in the Lagidium genus. Mountain Viscachas generally give birth to a single offspring after a long gestation period, ensuring that each newborn has a better chance of survival in the unforgiving terrain. Born with fur and open eyes, young Viscachas are relatively well-developed, an adaptation that allows them to quickly learn the skills needed to navigate their hazardous mountain environment.

FAQs

Are Ecuadorean Viscachas related to rabbits or chinchillas?

Despite their rabbit-like appearance, Ecuadorean Viscachas belong to the Chinchillidae family, making them closer relatives of chinchillas than rabbits. Their long whiskers, dense fur, and powerful hind legs are adaptations seen in other members of this family, allowing them to thrive in rocky, high-altitude environments.

How are Ecuadorean Viscachas different from other Mountain Viscachas?

Ecuadorean Viscachas are the northernmost species of the Lagidium genus, separated by more than 500 kilometres from their closest relatives in Peru. Genetic studies show that they diverged significantly from other Mountain Viscachas, with at least 7.9% DNA sequence differences. Morphologically, they have a more compact body, a distinct black dorsal stripe, and a tail that shifts in colour from grey-brown to reddish-brown. Their isolation and unique adaptations to the Cerro El Ahuaca environment make them a distinct species.

How do Ecuadorean Viscachas survive in their rocky habitat?

Perfectly adapted to life among sheer cliffs and granite outcrops, Ecuadorean Viscachas use their powerful hind legs to leap between rocks, navigating the treacherous terrain with ease. Their thick, woolly fur provides insulation against the cold, and instead of burrowing, they take refuge in rock crevices where they remain hidden from predators.

What do Ecuadorean Viscachas eat?

These herbivores feed on native shrubs, grasses, and small herbs found in their mountainous habitat. They leave behind distinct feeding traces, such as grazed vegetation and stripped plants, which provide insight into their foraging habits. Their diet is dictated by the limited plant life available in their isolated environment.

How many Ecuadorean Viscachas are left in the wild?

The total known population is alarmingly small, possibly consisting of only a few dozen individuals confined to a 120-hectare area on Cerro El Ahuaca. No other populations have been discovered, making them one of the most critically endangered rodents in the world.

What are the biggest threats to the Ecuadorean Viscacha?

Their biggest threats include:

• Habitat destruction – Uncontrolled fires and land clearing for eucalyptus and pine monoculture and cattle grazing are steadily erasing their already limited habitat.

• Livestock competition – Grazing cattle trample vegetation and outcompete Viscachas for food.

• Climate change – Shifting rainfall patterns and temperature fluctuations could further disrupt their delicate ecosystem.

• Genetic isolation – With only a single known population, they face the risk of inbreeding, which could weaken their resilience.

Why are they only found in one place?

Ecuadorean Viscachas are highly specialised mountain dwellers, perfectly suited to the rocky terrain of Cerro El Ahuaca. They may have once had a wider range, but habitat destruction and fragmentation have left them stranded in this isolated stronghold. Unlike more adaptable rodents, they cannot easily move to new areas due to their specific habitat needs.

Are Ecuadorean Viscachas protected?

The Ecuadorean Vischaca was only recently discovered and are considered a forgotten species. However conservation efforts have begun, there is no targeted species-wide protection in place. However, local conservation initiatives have helped establish protected areas that include their habitat. Researchers continue to push for stronger conservation measures to ensure their survival.

How can I help save the Ecuadorean Viscacha?

You can make a difference by:

• Supporting conservation organisations working to protect their habitat.

• Raising awareness about the threats they face by sharing this post and joining the #Boycott4Wildlife

• Advocating for stronger environmental policies in Ecuador to prevent further deforestation and habitat loss.

Without immediate action, these rare and remarkable mountain survivors could disappear forever.

Take Action!

The Ecuadorean Viscacha is teetering on the edge of extinction, but there is still time to act. Conservationists have already taken steps to protect their habitat, securing key areas under municipal conservation agreements. However, long-term survival depends on preventing further destruction of their fragile mountain refuge.

You can help by:

• Supporting organisations working to protect Ecuador’s high-altitude ecosystems.

• Spreading awareness about the threats facing the Ecuadorean Viscacha and the urgent need for conservation.

• Demanding stronger environmental protections to prevent further habitat loss in Loja Province.

Every effort counts. Without immediate action, these extraordinary mountain survivors could disappear forever.

Support Ecuadorean Viscacha by going vegan and boycotting palm oil in the supermarket, it’s the #Boycott4Wildlife

Support the conservation of this species

This animal has no protections in place. Read about other forgotten species here. Create art to support this forgotten animal or raise awareness about them by sharing this post and using the #Boycottpalmoil #Boycott4Wildlife hashtags on social media. Also you can boycott palm oil in the supermarket.

Further Information

Nature and Culture International. (2022). Ecuadorian Viscacha Conservation Project. Retrieved from https://www.natureandculture.org/directory/ecuadorian-vizcacha-conservation-project/

Roach, N. 2016. Lagidium ahuacaense. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2016: e.T48295808A48295811. https://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2016-2.RLTS.T48295808A48295811.en. Accessed on 27 February 2025.

Werner, F. A., Ledesma, K. J., & Hidalgo B., R. (2006). Mountain vizcacha (Lagidium cf. peruanum) in Ecuador – first record of Chinchillidae from the northern Andes. Mastozoología Neotropical, 13(2), 271–274.

Wikipedia Contributors. (n.d.). Lagidium ahuacaense. Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Retrieved from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lagidium_ahuacaense

How can I help the #Boycott4Wildlife?

Take Action in Five Ways

1. Join the #Boycott4Wildlife on social media and subscribe to stay in the loop: Share posts from this website to your own network on Twitter, Mastadon, Instagram, Facebook and Youtube using the hashtags #Boycottpalmoil #Boycott4Wildlife.

Enter your email address

Sign Up

Join 3,529 other subscribers2. Contribute stories: Academics, conservationists, scientists, indigenous rights advocates and animal rights advocates working to expose the corruption of the palm oil industry or to save animals can contribute stories to the website.

Wildlife Artist Juanchi Pérez

Mel Lumby: Dedicated Devotee to Borneo’s Living Beings

Anthropologist and Author Dr Sophie Chao

Health Physician Dr Evan Allen

The World’s Most Loved Cup: A Social, Ethical & Environmental History of Coffee by Aviary Doert

How do we stop the world’s ecosystems from going into a death spiral? A #SteadyState Economy

3. Supermarket sleuthing: Next time you’re in the supermarket, take photos of products containing palm oil. Share these to social media along with the hashtags to call out the greenwashing and ecocide of the brands who use palm oil. You can also take photos of palm oil free products and congratulate brands when they go palm oil free.

https://twitter.com/CuriousApe4/status/1526136783557529600?s=20

https://twitter.com/PhillDixon1/status/1749010345555788144?s=20

https://twitter.com/mugabe139/status/1678027567977078784?s=20

4. Take to the streets: Get in touch with Palm Oil Detectives to find out more.

5. Donate: Make a one-off or monthly donation to Palm Oil Detectives as a way of saying thank you and to help pay for ongoing running costs of the website and social media campaigns. Donate here

Pledge your supportLearn about other animals endangered by palm oil and other agriculture

GlobalSouth America S.E. AsiaIndiaAfricaWest Papua & PNG

Southern Pudu Pudu puda

Blue-streaked Lory Eos reticulata

Blonde Capuchin Sapajus flavius

Savage’s Glass Frog Centrolene savagei

Pesquets Parrot Psittrichas fulgidus

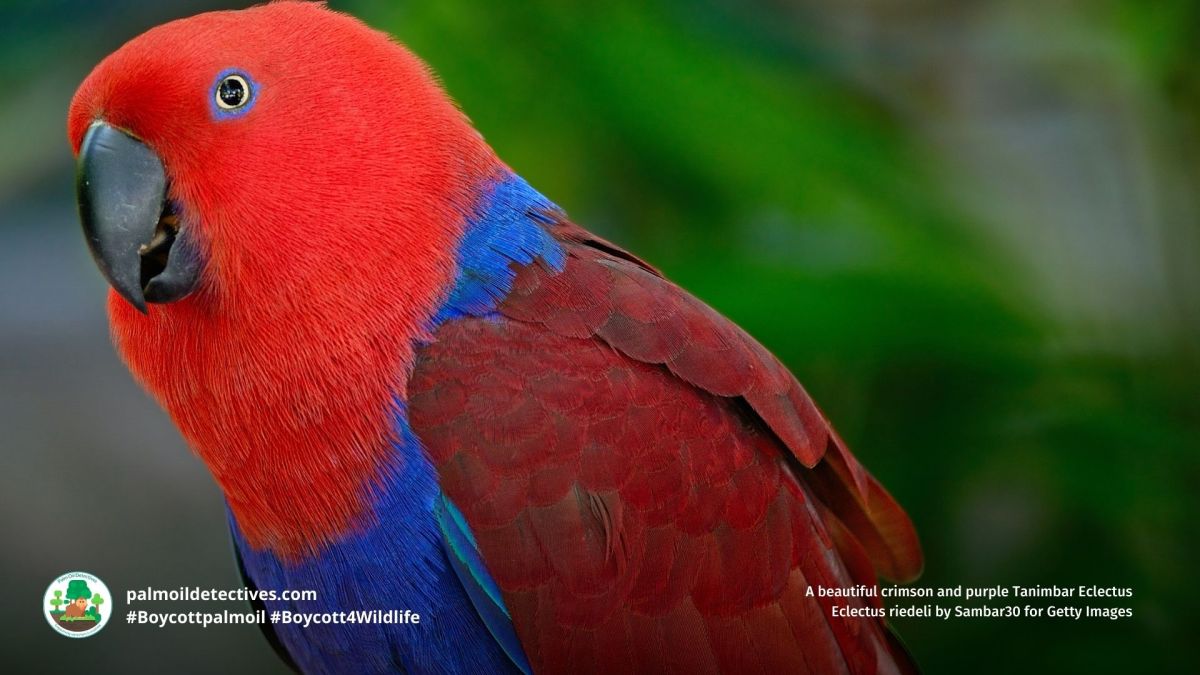

Tanimbar Eclectus Parrot Eclectus riedeli

Learn about “sustainable” palm oil greenwashing

Read more about RSPO greenwashing

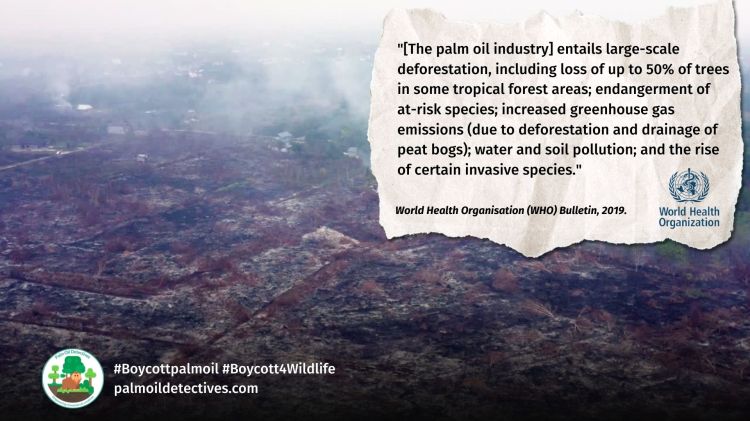

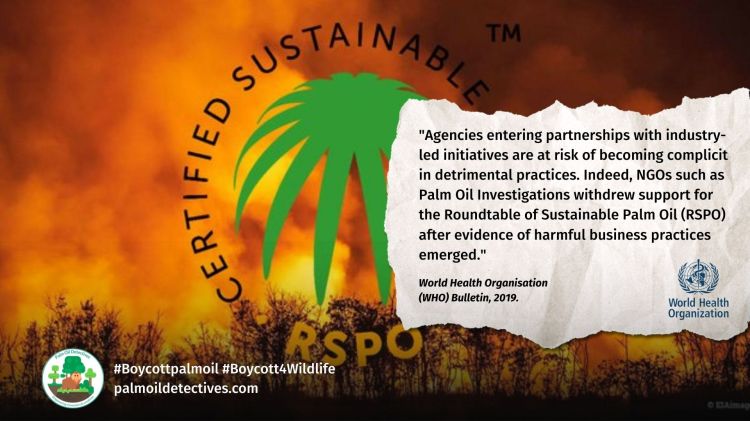

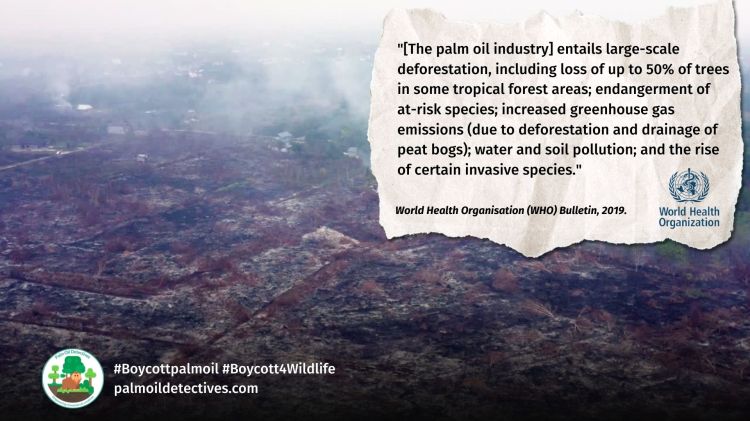

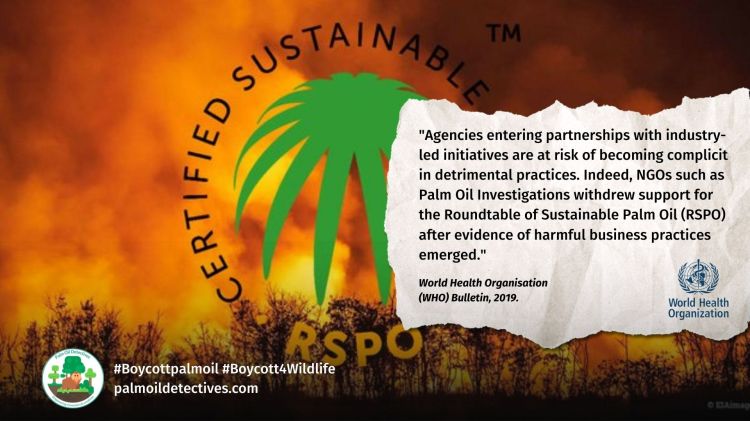

Lying Fake labelsIndigenous Land-grabbingHuman rights abusesDeforestation Human health hazardsA 2019 World Health Organisation (WHO) report into the palm oil industry and RSPO finds extensive greenwashing of palm oil deforestation and the murder of endangered animals (i.e. biodiversity loss)

Read more

#Agriculture #animals #beef #Boycott4wildlife #BoycottPalmOil #climatechange #CriticallyEndangeredSpecies #criticallyendangered #deforestation #Ecuador #EcuadoreanViscachaLagidiumAhuacaense #endangered #extinction #ForgottenAnimals #hunting #meat #meatDeforestation_ #PalmOil #palmOilDeforestation #Peru #poaching #rodent #rodents #SouthAmericaSpeciesEndangeredByPalmOilDeforestation #vegan #Viscacha

Tucuxi Sotalia fluviatilis

Tucuxi Sotalia fluviatilis

IUCN Red List Status: Endangered

Location: #Brazil, #Peru, #Colombia, #Ecuador

Found throughout the #Amazon and Solimões River systems, including major tributaries and large lakes. Their range spans lowland rainforest areas of Brazil, southeastern Colombia, eastern Ecuador, and southern Peru.

The #Tucuxi, a small freshwater #dolphin of #Peru, #Ecuador, #Colombia and #Brazil now faces a dire future. Once common throughout the Amazon River system, they are now listed as #Endangered due to accelerating population declines. Threats include drowning in fishing nets, deforestation, mercury poisoning from gold mining, #palmoil run-off, oil drilling, and dam construction. A shocking 97% decline was recorded over 23 years in a single Amazon reserve. Without urgent action, this elegant and playful river dolphin could vanish from South America’s waterways. Use your wallet as a weapon against extinction. Choose palm oil-free, and #BoycottGold #BoycottPalmOil #Boycott4Wildlife

Playful and intelligent #Tucuxi are small #dolphins 🐬 of #Amazonian rivers in #Peru 🇵🇪 #Brazil 🇧🇷 #Ecuador 🇪🇨 and #Colombia 🇨🇴. #PalmOil and #GoldMining are major threats 😿 Fight for them! #BoycottGold #BoycottPalmOil #Boycott4Wildlife @palmoildetect https://palmoildetectives.com/2025/11/23/tucuxi-sotalia-fluviatilis/

Share to BlueSky Share to TwitterClever and joyful #Tucuxi are #dolphins 🐬💙 endangered by #hunting #gold #mining and contamination of the Amazon river 🇧🇷 for #PalmOil #agriculture ☠️ Use your wallet as a weapon and #BoycottGold 🥇🚫 #BoycottPalmOil 🌴🚫 #Boycott4Wildlife @palmoildetect https://palmoildetectives.com/2025/11/23/tucuxi-sotalia-fluviatilis/

Share to BlueSky Share to TwitterAppearance & Behaviour

Tucuxis are often mistaken for their oceanic dolphin cousins due to their streamlined bodies, short beaks, and smooth, pale-to-dark grey skin. But these freshwater dolphins are wholly unique—adapted to life in winding river systems where water levels rise and fall dramatically with the seasons.

What sets them apart is their remarkable intelligence and tightly knit social groups. Tucuxis are playful and curious by nature. They leap from the water in graceful arcs, sometimes spinning mid-air.

The Tucuxi, sometimes called the ‘grey dolphin’ due to their uniform colouring, resembles a smaller oceanic dolphin, with a streamlined body and slender beak. Their colour varies from pale grey on the belly to darker grey or bluish-grey along the back.

They travel in small groups of two to six, displaying coordinated swimming patterns. In rare cases, they may form groups up to 26 individuals, particularly at river confluences. Known for their agility, they leap and spin in the water with a grace that belies their size. Tucuxis are particularly drawn to dynamic habitats like river junctions, where waters mix and fish gather.

Threats

- Widespread deforestation from palm oil plantations Palm oil plantations are rapidly expanding across the Amazon, clearing vast tracts of forest that stabilise riverbanks and filter water. This deforestation leads to increased sedimentation in rivers, altering flow patterns and reducing water clarity—conditions that directly disrupt the Tucuxi’s feeding and movement. Run-off from fertilisers and pesticides used in palm oil monocultures also poisons aquatic ecosystems, harming Tucuxis other Amazonian dolphin species and the fish they rely on.

- Toxic mercury pollution from gold mining Artisanal and illegal gold mining in the Amazon releases massive quantities of mercury into the water, contaminating fish and other aquatic organisms. Tucuxis, as top predators, ingest this mercury through their prey, which accumulates in their tissues and causes neurological damage, weakened immunity, and reproductive failure. Mercury exposure is one of the most insidious threats, as it persists in ecosystems long after mining has ceased.

- Incidental drowning in fishing nets Tucuxis are frequently caught and killed in gillnets and other fishing gear as bycatch. Tucuxis and other Amazonian dolphins often inhabit the same confluence zones and productive fishing grounds targeted by local communities, making entanglement almost inevitable. Many carcasses are never recovered, having either been discarded by fishers or lost to river currents, meaning actual mortality rates are likely far higher than reported.

- Deliberate hunting for use as fish bait Though illegal, Tucuxis continue to be targeted and killed in parts of Brazil, especially near the Mamirauá and Amana Reserves, where they are used as bait in the piracatinga (catfish) fishery. This brutal practice involves harpooning or netting dolphins and using their flesh to lure fish, often alongside the killing of Botos. Despite a national ban, weak enforcement and ongoing demand mean this threat persists in remote and lawless regions.

- Illegal fishing with explosives and toxins In certain areas, particularly in Brazil and Peru, fishers use home-made explosives and poisoned bait to stun or kill fish en masse. These destructive methods harm or kill Tucuxis who are attracted by the sudden appearance of dead or stunned prey. The concussive force of explosions and the ingestion of poisoned prey result in slow, agonising deaths for affected dolphins.

- Construction of hydroelectric dams Dams fragment Tucuxi populations by blocking their movement along river corridors, reducing access to feeding and breeding grounds. These projects alter seasonal water flow, raise water temperatures, and flood critical habitats—conditions that significantly disrupt dolphin ecology. Brazil alone has 74 operational dams in the Amazon basin, with over 400 more planned, posing a long-term existential threat to freshwater cetaceans.

- Run-off and contamination from palm oil, soy and meat agriculture In addition to habitat loss, palm oil and soy plantations along with cattle ranching generates enormous volumes of chemical-laden waste, which enters waterways and poisons aquatic life. This pollution affects Tucuxis both directly and indirectly—exposing them to harmful substances and killing off sensitive fish species. As plantations replace biodiverse forests, the ecosystem becomes less resilient, accelerating the decline of species like the Tucuxi.

- Bioaccumulation of heavy metals and industrial pollutants Tucuxis, like many river dolphins, suffer from exposure to persistent organic pollutants such as PCBs, DDT, and flame retardants, as well as heavy metals like lead and cadmium. These toxins accumulate in dolphin tissues over time, weakening their immune systems, interfering with reproduction, and making them more vulnerable to disease. Contaminants originate from industrial waste, agriculture, and mining, and are now widespread across the Amazon basin.

- Habitat fragmentation from infrastructure and oil development Roads, oil pipelines, and shipping corridors criss-cross many parts of the Tucuxi’s range, slicing through their habitat and increasing the risk of collisions with boats. These developments also bring noise pollution, which can interfere with echolocation and communication. Fragmentation leads to isolated subpopulations, reducing genetic diversity and making recovery more difficult.

Geographic Range

The Tucuxi inhabits the Amazon River basin, spanning: Brazil, Peru, Colombia, Ecuador These river dolphins occur as far west as southern Peru and eastern Ecuador, and as far north as southeastern Colombia. They are notably absent from Bolivia’s Beni/Mamoré system, the Orinoco basin, and upper reaches above major waterfalls or rapids.

Their range includes wide, deep rivers and lakes, avoiding turbulent rapids and shallow areas. Despite overlapping with the Amazon River Dolphin (Inia geoffrensis), Tucuxis do not enter flooded forest habitats and stay closer to main river channels.

Diet

Tucuxis feed on more than 28 species of small, schooling freshwater fish, including members of the characid, sciaenid, and siluriform families. During the dry season, fish are concentrated in shrinking waterways, making them easier to catch. In contrast, flooding season disperses prey into forested areas, beyond the Tucuxi’s reach. They prefer to feed at river junctions and along confluences, where nutrient-rich waters concentrate fish populations.

Mating and Reproduction

Little is known about their mating behaviours. However, individuals appear to remain within familiar ranges for many years, and females likely give birth to a single calf after a long gestation. Calves are dependent for an extended period, learning complex navigation and foraging skills in rapidly changing river systems. The estimated generation length is 15.6 years.

FAQs

How many Tucuxis are left in the wild?

There is no comprehensive global population estimate. However, surveys from 1994–2017 in Brazil’s Mamirauá Reserve show a 7.4% annual decline—amounting to a 97% drop over three generations (da Silva et al., 2020). If this trend reflects the wider Amazon basin, the species could be on the brink of collapse.

How long do Tucuxis live?

Exact lifespans are unknown, but based on reproductive data and life history modelling, their generation length is around 15.6 years (Taylor et al., 2007), suggesting natural lifespans of 30–40 years.

How are palm oil and gold mining affecting Tucuxis?

Out-of-control palm oil expansion results in massive deforestation and run-off, clogging rivers with sediment and toxic agrochemicals. Gold mining adds mercury into aquatic ecosystems, where it bioaccumulates in fish—Tucuxis’ main food source. These pollutants cause reproductive harm, neurological damage, and immune system failure in dolphins.

Do Tucuxis make good pets and should they be kept in zoos?

Absolutely not. Tucuxis are intelligent, wild animals. Keeping them in captivity is deeply cruel and has no conservation benefit. Wild capture destroys families and can devastate local populations. If you care about these dolphins, say no to the exotic pet trade and the cruel zoo trade.

What habitats do they prefer?

Research in Peru’s Pacaya-Samiria Reserve shows that Tucuxis prefer river confluences and wide channels, particularly during the dry season when fish density is higher (Belanger et al., 2022). Feeding activity is especially concentrated in areas where whitewater rivers meet blackwater tributaries, creating nutrient-rich hotspots.

Take Action!

The Tucuxi is vanishing before our eyes. To protect them:

• Boycott palm oil and gold products linked to Amazon destruction.

• Choose fish-free and vegan products to reduce pressure on river ecosystems.

• Support indigenous-led conservation across the Amazon.

• Campaign for a ban on destructive dams, and the end of illegal fishing.

#BoycottPalmOil #Boycott4Wildlife #Vegan #BoycottMeat

Support the Tucuxi by going vegan and boycotting palm oil in the supermarket, it’s the #Boycott4Wildlife

Support the conservation of this species

This animal has no protections in place. Read about other forgotten species here. Create art to support this forgotten animal or raise awareness about them by sharing this post and using the #Boycottpalmoil #Boycott4Wildlife hashtags on social media. Also you can boycott palm oil in the supermarket.

Further Information

Belanger, A., Wright, A., Gomez, C., Shutt, J.D., Chota, K., & Bodmer, R. (2022). River dolphins (Inia geoffrensis and Sotalia fluviatilis) in the Peruvian Amazon: habitat preferences and feeding behaviour. Latin American Journal of Aquatic Mammals, 17(1). https://doi.org/10.5597/lajam00268

da Silva, V., Martin, A., Fettuccia, D., Bivaqua, L. & Trujillo, F. 2020. Sotalia fluviatilis. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2020: e.T190871A50386457. https://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2020-3.RLTS.T190871A50386457.en. Accessed on 06 April 2025.

Monteiro-Neto, C., Itavo, R. V., & Moraes, L. E. S. (2003). Concentrations of heavy metals in Sotalia fluviatilis (Cetacea: Delphinidae) off the coast of Ceará, northeast Brazil. Environmental Pollution, 123(2), 319–324. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0269-7491(02)00371-8

How can I help the #Boycott4Wildlife?

Take Action in Five Ways

1. Join the #Boycott4Wildlife on social media and subscribe to stay in the loop: Share posts from this website to your own network on Twitter, Mastadon, Instagram, Facebook and Youtube using the hashtags #Boycottpalmoil #Boycott4Wildlife.

Enter your email address

Sign Up

Join 3,172 other subscribers2. Contribute stories: Academics, conservationists, scientists, indigenous rights advocates and animal rights advocates working to expose the corruption of the palm oil industry or to save animals can contribute stories to the website.

Wildlife Artist Juanchi Pérez

Mel Lumby: Dedicated Devotee to Borneo’s Living Beings

Anthropologist and Author Dr Sophie Chao

Health Physician Dr Evan Allen

The World’s Most Loved Cup: A Social, Ethical & Environmental History of Coffee by Aviary Doert

How do we stop the world’s ecosystems from going into a death spiral? A #SteadyState Economy

3. Supermarket sleuthing: Next time you’re in the supermarket, take photos of products containing palm oil. Share these to social media along with the hashtags to call out the greenwashing and ecocide of the brands who use palm oil. You can also take photos of palm oil free products and congratulate brands when they go palm oil free.

https://twitter.com/CuriousApe4/status/1526136783557529600?s=20

https://twitter.com/PhillDixon1/status/1749010345555788144?s=20

https://twitter.com/mugabe139/status/1678027567977078784?s=20

4. Take to the streets: Get in touch with Palm Oil Detectives to find out more.

5. Donate: Make a one-off or monthly donation to Palm Oil Detectives as a way of saying thank you and to help pay for ongoing running costs of the website and social media campaigns. Donate here

Pledge your supportLearn about other animals endangered by palm oil and other agriculture

GlobalSouth America S.E. AsiaIndiaAfricaWest Papua & PNG

Frill-Necked Lizard Chlamydosaurus kingii

Grey Crowned Crane Balearica regulorum

Ecuadorean Viscacha Lagidium ahuacaense

Southern Pudu Pudu puda

Blue-streaked Lory Eos reticulata

Blonde Capuchin Sapajus flavius

Learn about “sustainable” palm oil greenwashing

Read more about RSPO greenwashing

Lying Fake labelsIndigenous Land-grabbingHuman rights abusesDeforestation Human health hazardsA 2019 World Health Organisation (WHO) report into the palm oil industry and RSPO finds extensive greenwashing of palm oil deforestation and the murder of endangered animals (i.e. biodiversity loss)

Read more

#agriculture #amazon #amazonRainforest #amazonia #amazonian #animalCruelty #animals #boycott4wildlife #boycottgold #boycottmeat #boycottpalmoil #brazil #colombia #dams #deforestation #dolphin #dolphins #ecuador #endangered #endangeredSpecies #forgottenAnimals #gold #goldMining #goldmining #humanWildlifeConflict #hunting #hydroelectric #mammal #mining #palmOil #palmOilDeforestation #palmoil #peru #poaching #saynotogold #tucuxi #tucuxiSotaliaFluviatilis #vegan

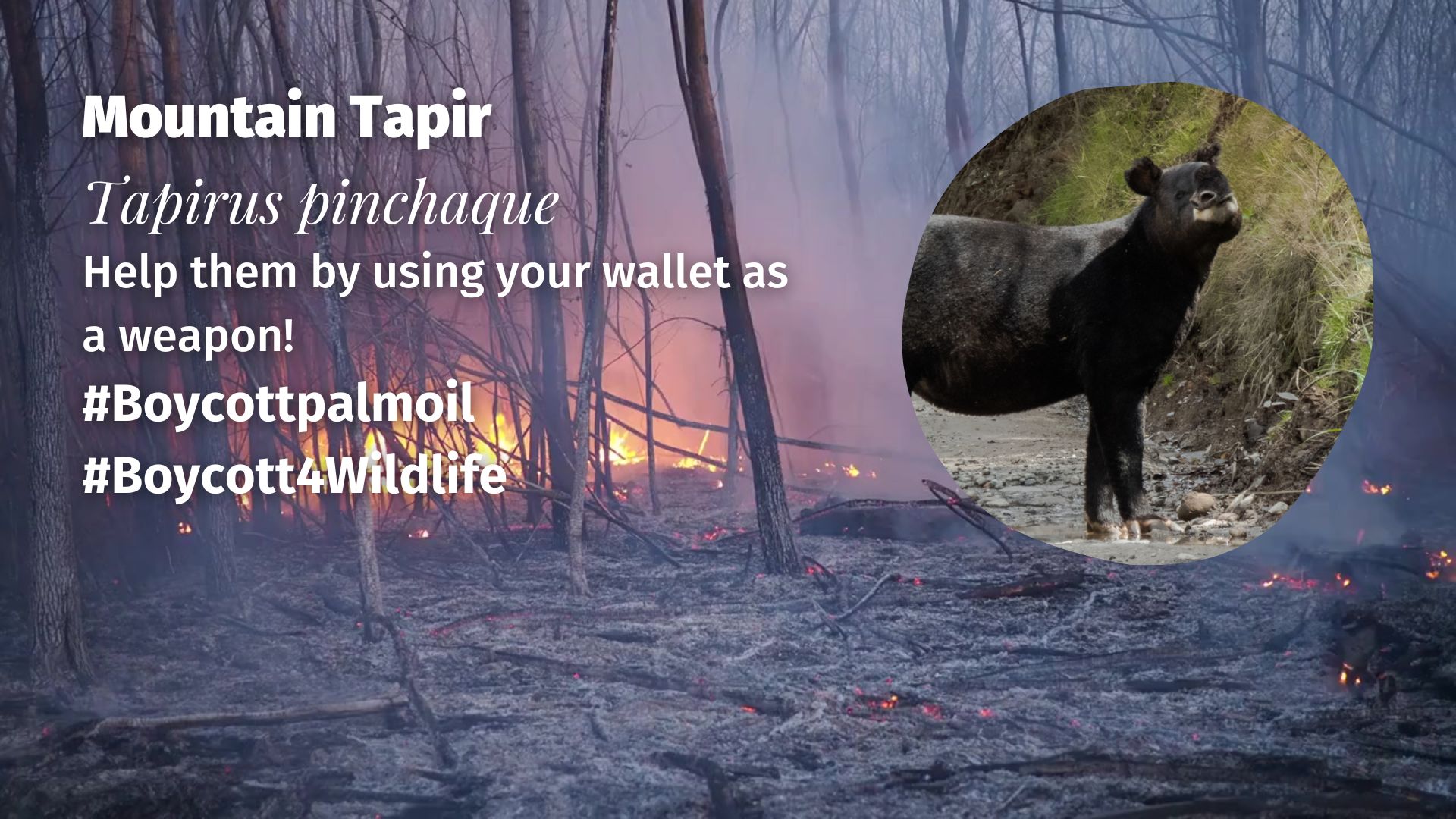

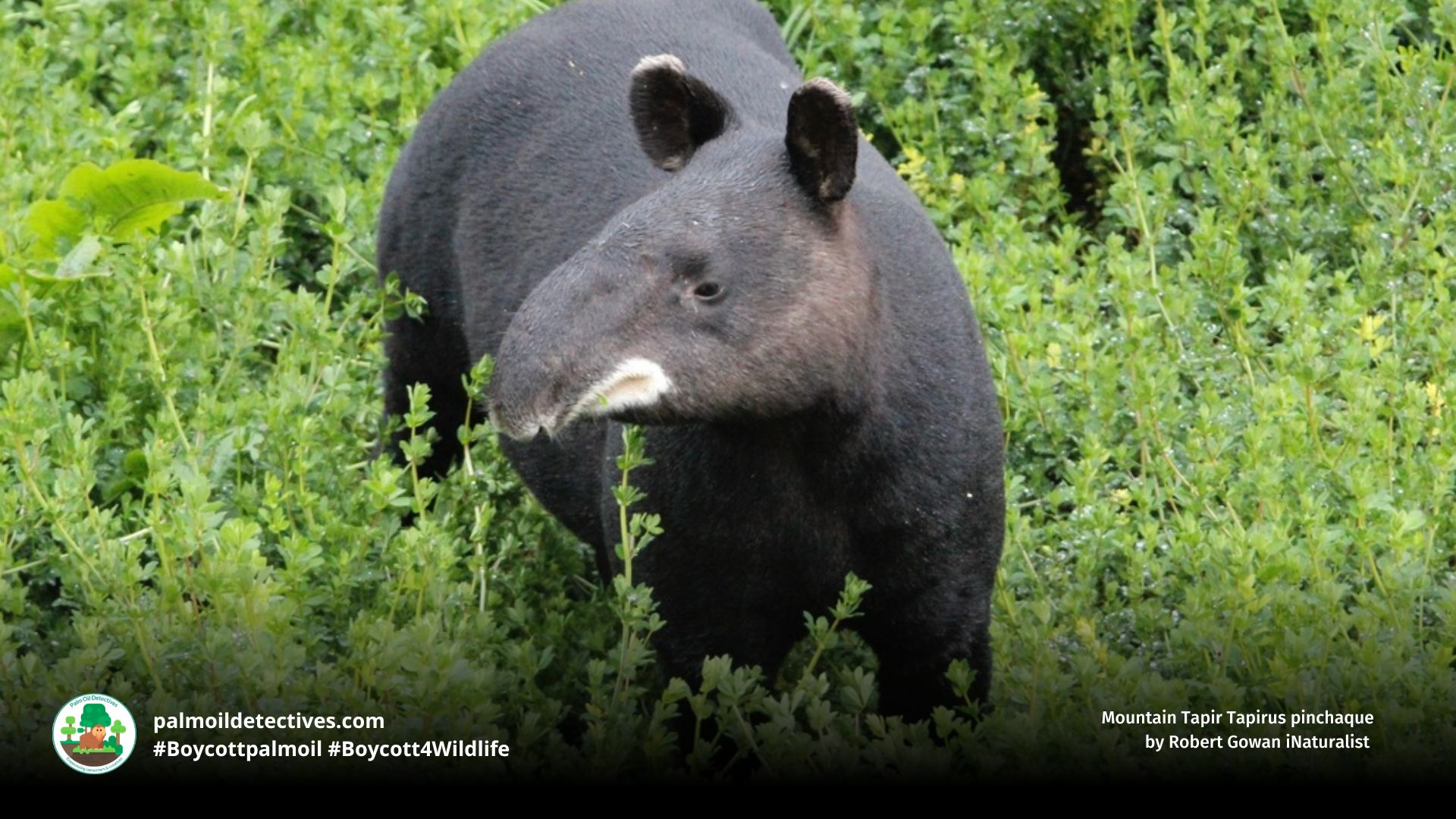

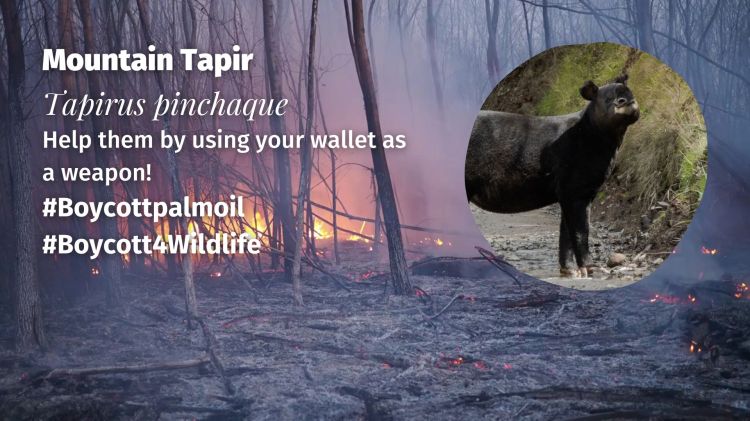

Mountain Tapir Tapirus pinchaque

Mountain Tapir Tapirus pinchaque

IUCN Red List Status: Endangered

Location: Colombia, Ecuador, northern Peru

Mountain Tapirs inhabit the high Andean cloud forests and páramos above 2,000 metres in the northern Andes. They are found in Colombia’s Central and Eastern Cordilleras, throughout Ecuador including Sangay and Podocarpus National Parks, and into northern Peru, notably in Cajamarca and Lambayeque.

The Mountain Tapir Tapirus pinchaque is one of the most threatened large mammals in the northern Andes, currently listed as Endangered. Their populations have declined by over 50% in the past three decades due to habitat loss, illegal hunting, climate change, and rampant mining. With fewer than 2,500 mature individuals remaining, they are quietly disappearing from their mist-shrouded mountain homes. Human encroachment, infrastructure development, and cattle grazing now invade their last strongholds. Without urgent action, they may vanish forever. Use your wallet as a weapon and fight back when you shop #BoycottPalmOil #Boycott4Wildlife and be #BoycottGold

Sweet-natured Mountain #Tapirs of #Ecuador 🇪🇨 #Peru 🇵🇪 and #Colombia 🇨🇴 face serious threats incl. illegal crops, #gold #mining, #palmoil #deforestation and hunting. Help them survive #BoycottPalmOil 🌴⛔️#BoycottGold 🥇⛔️ #Boycott4Wildlife @palmoildetect https://palmoildetectives.com/2025/12/28/mountain-tapir-tapirus-pinchaque/

Share to BlueSky Share to TwitterThe Wooly #Tapir AKA Mountain Tapir gives birth to one calf at a time 🩷😻 They’re #endangered due to a many threats: #climatechange and #pollution from #gold mining. Resist for them! #BoycottPalmOil #BoycottGold 🥇☠️❌ #Boycott4Wildlife @palmoildetect https://palmoildetectives.com/2025/12/28/mountain-tapir-tapirus-pinchaque/

Share to BlueSky Share to TwitterAppearance & Behaviour

Also known as the woolly tapir for their thick, dark, shaggy coat, Mountain Tapirs are built to survive in the cold, damp cloud forests and páramo grasslands. Their dense fur, white lips, and prehensile snout give them an almost prehistoric appearance. These solitary and elusive mammals are primarily nocturnal and crepuscular, navigating dense foliage with ease. Once thought to be loners, long-term studies in Ecuador have revealed that they form small, close-knit family groups, with calves gradually dispersing over several years (Castellanos et al., 2022).

Threats

Deforestation for palm oil, meat agriculture and illicit opium/coca cultivation

Large swathes of Andean cloud forest and páramo are being cleared to make way for palm oil agricultural expansion, cattle grazing, and opium or coca cultivation. These activities are not only destroying core habitat but also breaking up previously connected populations, leaving tapirs isolated and vulnerable to local extinctions. The introduction of cattle into remote tapir refuges has become increasingly common, even inside designated national parks such as Sangay in Ecuador. This leads to trampling of sensitive vegetation, direct competition for food, and destruction of the unique montane ecosystems that Mountain Tapirs rely on for survival.

Illegal hunting for meat, traditional medicine, and cultural uses

Although hunting pressure has declined slightly in Ecuador due to greater public awareness, it remains severe in Colombia and Peru. Tapirs are killed for their meat, and their skins are used to make traditional tools, horse gear, carpets, and bed covers. Additionally, body parts are sold in local markets or prescribed by shamans for use in traditional medicine. In many remote areas, Mountain Tapirs are still being actively poached, and it is now rare to find populations that are not affected by some form of overhunting.

Gold mining and illegal mining causing deforestation and poisoning of ecosystems

Gold mining projects in the northern Peruvian Andes and central Colombia are rapidly destroying the last cloud forest headwaters and páramo ecosystems where tapirs persist. Both legal and illegal mining operations contaminate streams and watersheds with heavy metals and toxic runoff, which has severe consequences for both tapirs and the human communities downstream. Mining also brings roads, noise, and human settlements into previously inaccessible areas, increasing hunting pressure and reducing available habitat. In some parts of Peru, nearly 30% of the Mountain Tapir’s current range now overlaps with active or planned gold mining concessions (More et al., 2022).

Climate change pushing tapirs further uphill into shrinking habitat

As global temperatures rise, the high-elevation ecosystems where Mountain Tapirs live are shrinking. Suitable climate zones are shifting higher up the mountains, but because mountains have limited space at the top, this forces tapirs into ever smaller areas with fewer food resources. This phenomenon, known as “the escalator to extinction,” is especially dangerous for highland species like the Mountain Tapir, who cannot move downward into warmer zones. Climate change also alters rainfall patterns and vegetation cycles, further straining the species’ delicate habitat requirements.

Road construction and vehicle collisions within protected areas

Infrastructure development is rapidly cutting through mountainous areas, including roads that bisect national parks and reserves. This not only fragments tapir habitat but also leads to direct deaths through vehicle collisions. Once roads are completed, traffic speeds increase and tapirs crossing roads—especially at dawn and dusk—become highly vulnerable. Roads also make previously remote areas more accessible to poachers, settlers, and resource extractors, while local governments often lack sufficient ranger staff to monitor and protect these newly exposed areas.

Fumigation campaigns using toxic chemicals to eradicate drug crops

In Colombia, the government authorises aerial fumigation of coca and poppy fields using glyphosate-based herbicides like Round-Up. These chemicals are sprayed over wide areas, including forests and National Parks, contaminating soil, plants, and water sources. Mountain Tapirs can absorb these toxins through skin contact or ingestion, potentially leading to illness, reproductive failure, or death. Fumigation also destroys native plants that tapirs rely on for food, further decreasing habitat quality in affected areas.

Widespread introduction of cattle and the threat of disease transmission

Domestic cattle are increasingly being introduced into mountain tapir habitat, especially within protected areas where enforcement is weak. These animals not only compete with tapirs for forage but also carry diseases such as bovine tuberculosis and foot-and-mouth disease. Disease outbreaks have already been documented among tapirs in other parts of Latin America and pose a serious threat to small, isolated populations. In the Andes, cattle often form feral herds that reproduce and spread deep into cloud forests, further eroding habitat integrity and increasing the risk of tapir extinction.

Weak enforcement of environmental laws and lack of large protected areas in Peru

Although some Mountain Tapir habitat falls within designated protected areas, law enforcement in Peru is generally under-resourced and poorly coordinated. Rangers are too few to patrol vast mountainous regions effectively, and illegal activities such as mining, logging, and hunting continue within protected boundaries. Furthermore, most reserves are too small or fragmented to support viable tapir populations over the long term. Without stronger policies, larger protected zones, and meaningful binational cooperation with Ecuador and Colombia, tapirs in Peru face an uncertain future.

Low reproductive rate and slow population recovery

Mountain Tapirs have a long gestation period of around 13 months and typically produce only one calf at a time, meaning population growth is inherently slow. When combined with high mortality from hunting, roadkill, and disease, their populations cannot recover quickly from losses. Calves stay with their mothers for extended periods, further limiting reproductive output. This slow life cycle makes the species particularly vulnerable to sudden or sustained threats across their fragmented range.

Geographic Range

This species is found in the high Andes of Colombia, Ecuador, and northernmost Peru. In Colombia, they are present in the Central and Eastern Cordilleras but are absent from the Western Cordillera and Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta. In Ecuador, they range from the central Andes down through Sangay National Park to Podocarpus, with new records emerging from previously unconnected areas in the western Andes. In Peru, they occur north and south of the Huancabamba River in Cajamarca and Lambayeque (More et al., 2022). The total range in Peru is estimated at 183,000 hectares, but mining concessions cover nearly 30% of this habitat.

Diet

Mountain Tapirs are browsers, feeding on a wide variety of vegetation including leaves, shoots, fruits, and bromeliads. Their diet varies depending on the availability of plants within their high-altitude habitats, playing an important role as seed dispersers within these fragile ecosystems.

Mating and Reproduction

Mountain Tapirs have a slow reproductive rate, with a gestation period of approximately 13 months. Females typically give birth to a single calf, which stays with them for several months or even years before dispersing. Calves are born with white stripes and spots that fade as they mature. Their slow breeding cycle makes it difficult for populations to recover from hunting and habitat loss.

FAQs

How many Mountain Tapirs are left in the wild?

Fewer than 2,500 mature individuals remain in the wild, and the population is continuing to decline by at least 20% every two decades due to ongoing threats like habitat destruction, hunting, and climate change (IUCN, 2015).

What is the average lifespan of a Mountain Tapir?

In the wild, Mountain Tapirs may live up to 25 years, though this is significantly affected by environmental threats. Captive individuals can live slightly longer under safe and controlled conditions.

What are the biggest challenges to conserving Mountain Tapirs?

Major challenges include habitat fragmentation due to road construction, agriculture, and mining; the presence of armed conflict zones that hinder research and protection; and the slow reproduction rate of the species, which makes population recovery difficult (Guzmán-Valencia et al., 2024; More et al., 2022).

Do Mountain Tapirs make good pets?

No. Keeping a Mountain Tapir as a pet is unethical and illegal. These intelligent, solitary animals require large, wild habitats to survive. Capturing and trading them causes immense suffering and drives the species further toward extinction. Advocating against the exotic pet trade is vital to their survival.

Take Action!

Boycott palm oil and products linked to Andean deforestation. Support indigenous-led conservation and agroecology initiatives in the Andes. Call for stronger protections against mining and deforestation in Colombia, Ecuador, and Peru. Refuse to buy exotic animal products, including those used in folk medicine. #BoycottPalmOil #Boycott4Wildlife #Vegan #BoycottMeat

Support Mountain Tapirs by going vegan and boycotting palm oil in the supermarket, it’s the #Boycott4Wildlife

Support the conservation of this species

This animal has no protections in place. Read about other forgotten species here. Create art to support this forgotten animal or raise awareness about them by sharing this post and using the #Boycottpalmoil #Boycott4Wildlife hashtags on social media. Also you can boycott palm oil in the supermarket.

Further Information

Castellanos, A., Dadone, L., Ascanta, M., & Pukazhenthi, B. (2022). Andean tapir (Tapirus pinchaque) social groups and calf dispersal patterns in Ecuador. Boletín Técnico, Serie Zoológica, 17, 9–14. Retrieved from https://journal.espe.edu.ec/ojs/index.php/revista-serie-zoologica/article/view/2858

Delborgo Abra, F., Medici, P., Brenes-Mora, E., & Castelhanos, A. (2024). The Impact of Roads and Traffic on Tapir Species. In Tapirs of the World (pp. 157–165). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-65311-7_10

Guzmán-Valencia, C., Castrillón, L., Roncancio Duque, N., & Márquez, R. (2024). Co-Occurrence, Occupancy and Habitat Use of the Andean Bear and Mountain Tapir: Insights for Conservation Management in the Colombian Andes. SSRN. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.5061561

Lizcano, D.J., Amanzo, J., Castellanos, A., Tapia, A. & Lopez-Malaga, C.M. 2016. Tapirus pinchaque. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2016: e.T21473A45173922. https://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2016-1.RLTS.T21473A45173922.en. Accessed on 06 April 2025.

More, A., Devenish, C., Carrillo-Tavara, K., Piana, R. P., Lopez-Malaga, C., Vega-Guarderas, Z., & Nuñez-Cortez, E. (2022). Distribution and conservation status of the mountain tapir (Tapirus pinchaque) in Peru. Journal for Nature Conservation, 66, 126130. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jnc.2022.126130

How can I help the #Boycott4Wildlife?

Take Action in Five Ways

1. Join the #Boycott4Wildlife on social media and subscribe to stay in the loop: Share posts from this website to your own network on Twitter, Mastadon, Instagram, Facebook and Youtube using the hashtags #Boycottpalmoil #Boycott4Wildlife.

Enter your email address

Sign Up

Join 3,174 other subscribers2. Contribute stories: Academics, conservationists, scientists, indigenous rights advocates and animal rights advocates working to expose the corruption of the palm oil industry or to save animals can contribute stories to the website.

Wildlife Artist Juanchi Pérez

Mel Lumby: Dedicated Devotee to Borneo’s Living Beings

Anthropologist and Author Dr Sophie Chao

Health Physician Dr Evan Allen

The World’s Most Loved Cup: A Social, Ethical & Environmental History of Coffee by Aviary Doert

How do we stop the world’s ecosystems from going into a death spiral? A #SteadyState Economy

3. Supermarket sleuthing: Next time you’re in the supermarket, take photos of products containing palm oil. Share these to social media along with the hashtags to call out the greenwashing and ecocide of the brands who use palm oil. You can also take photos of palm oil free products and congratulate brands when they go palm oil free.

https://twitter.com/CuriousApe4/status/1526136783557529600?s=20

https://twitter.com/PhillDixon1/status/1749010345555788144?s=20

https://twitter.com/mugabe139/status/1678027567977078784?s=20

4. Take to the streets: Get in touch with Palm Oil Detectives to find out more.

5. Donate: Make a one-off or monthly donation to Palm Oil Detectives as a way of saying thank you and to help pay for ongoing running costs of the website and social media campaigns. Donate here

Pledge your supportLearn about other animals endangered by palm oil and other agriculture

GlobalSouth America S.E. AsiaIndiaAfricaWest Papua & PNG

Saola Pseudoryx nghetinhensis

Tucuxi Sotalia fluviatilis

Frill-Necked Lizard Chlamydosaurus kingii

Grey Crowned Crane Balearica regulorum

Ecuadorean Viscacha Lagidium ahuacaense

Southern Pudu Pudu puda

Learn about “sustainable” palm oil greenwashing

Read more about RSPO greenwashing

Lying Fake labelsIndigenous Land-grabbingHuman rights abusesDeforestation Human health hazardsA 2019 World Health Organisation (WHO) report into the palm oil industry and RSPO finds extensive greenwashing of palm oil deforestation and the murder of endangered animals (i.e. biodiversity loss)

Read more

#animals #Bantrophyhunting #Boycott4wildlife #BoycottGold #BoycottMeat #BoycottPalmOil #cattle #climateChange #climatechange #Colombia #deforestation #Ecuador #endangered #EndangeredSpecies #ForgottenAnimals #gold #herbivore #herbivores #hunting #infrastructure #lowlandTapir #Mammal #mammals #mining #PalmOil #palmOilDeforestation #palmoil #Peru #poaching #pollution #Tapir #Tapirs #ungulate #ungulates #vegan

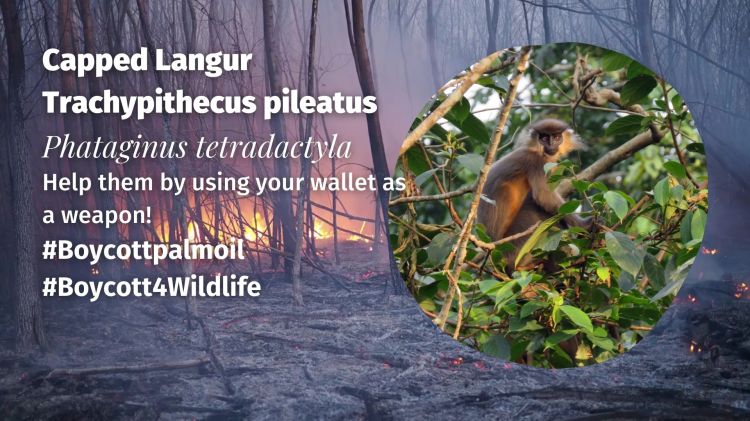

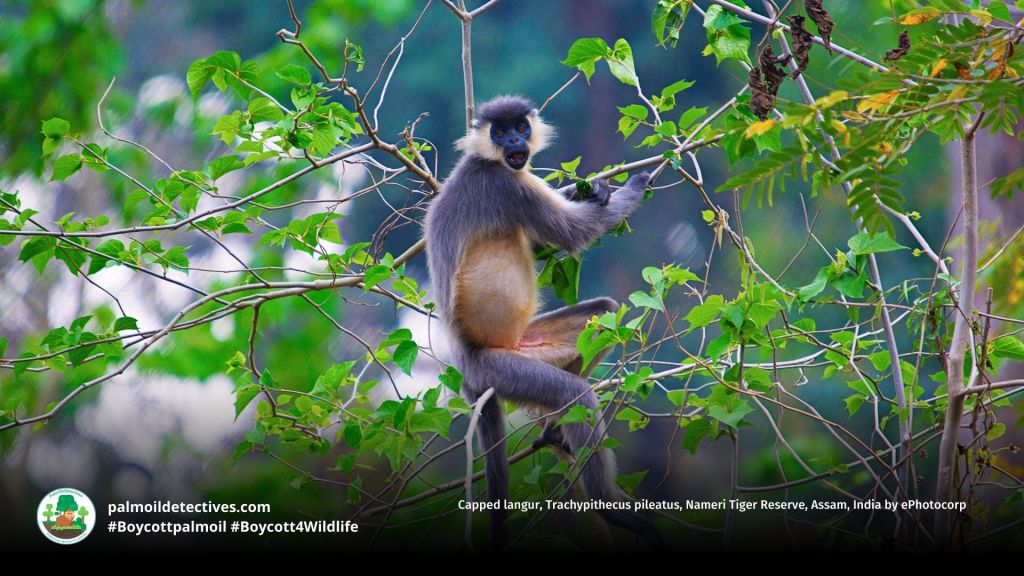

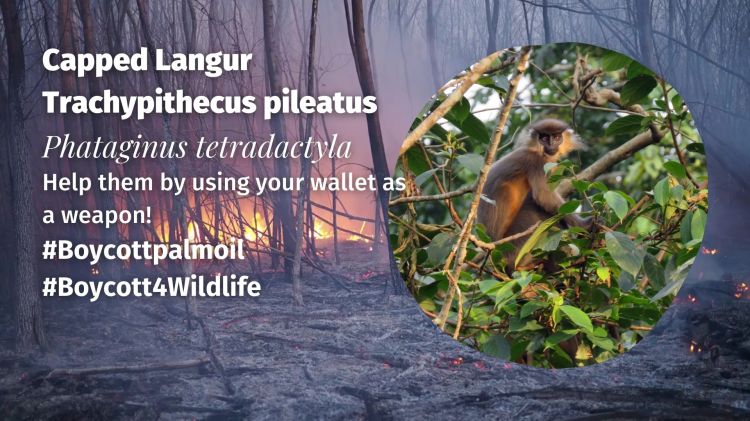

Capped Langur Trachypithecus pileatus

Capped Langur Trachypithecus pileatus

IUCN Red List Status: Vulnerable

Location: India, Bhutan, Bangladesh, Myanmar

This species inhabits subtropical and tropical dry forests, primarily in the foothills and highlands south of the Brahmaputra River and across fragmented patches in northeastern South Asia.

The capped #langur (Trachypithecus pileatus) is a graceful and beautiful leaf #monkey found across northeastern #India, #Bhutan, #Bangladesh, and #Myanmar. Sadly, they are listed as # Vulnerable on the IUCN Red List due to rapid population declines from #deforestation, logging, agriculture, and the devastating impacts of #palmoil plantations. Once widespread, their numbers have nearly halved in some regions like Assam due to the accelerating loss of native forest cover. Directly threatened by palm oil and monoculture expansion, this species is now confined to small, isolated forest fragments. Take action every time you shop and #BoycottPalmOil #Boycott4Wildlife

In the forests of #Bangladesh 🇧🇩 and northern #India 🇮🇳 lives a remarkable #primate with soulful hazel eyes 🐵🐒 on the verge of #extinction from #palmoil #deforestation. Help the Capped #Langur and #Boycottpalmoil 🌴🔥🚫 #Boycott4Wildlife @palmoildetect https://palmoildetectives.com/2026/01/11/capped-langur-trachypithecus-pileatus/

Share to BlueSky Share to TwitterThe intelligent and social Capped #Langur 🙉🐒🐵 is under pressure from #palmoil #deforestation and hunting in #India 🇮🇳 Troops are interbreeding with Phayre’s #langurs to survive. Fight for them and #Boycottpalmoil 🌴☠️❌ #Boycott4Wildlife @palmoildetect https://palmoildetectives.com/2026/01/11/capped-langur-trachypithecus-pileatus/

Share to BlueSky Share to TwitterAppearance & Behaviour

With their black-tufted crown, pale fur, and soulful eyes, capped langurs are among the most visually distinctive primates in the Eastern Himalayas. Their fur ranges from silver-grey to golden orange, with darker limbs and a black cap that gives them their name. They move gracefully through the canopy, rarely descending to the forest floor except for play or social grooming.

Capped langurs live in unimale, multifemale groups with sizes ranging from 8 to 15 individuals. They spend most of their time feeding (up to 67%) or resting (up to 40%), engaging in complex social grooming and vocal communication. Daily movements range from 320–800 metres across fragmented habitats of 21–64 hectares. Grooming is an important social activity, with females often taking turns in allomothering behaviour.

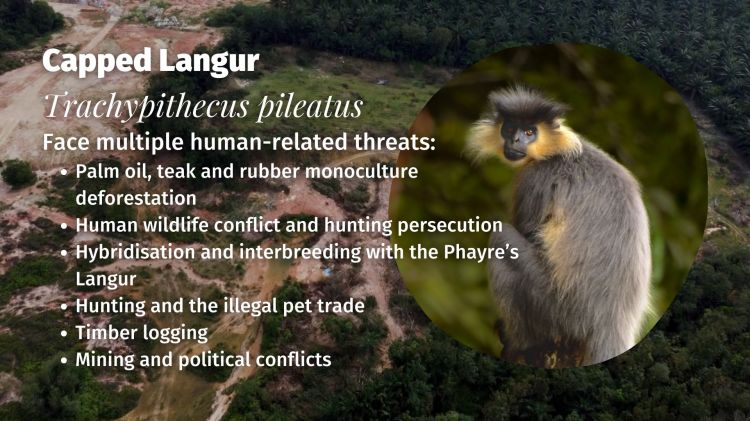

Threats

Palm oil, teak and rubber monoculture plantations

The spread of oil palm and other monoculture crops such as teak and rubber is destroying the capped langur’s native forests at an alarming rate. These industrial plantations eliminate the diverse tree species that capped langurs rely on for food and shelter, leaving them with little to survive on. Once a landscape is cleared and replaced with palm oil or other single crops, it becomes a green desert devoid of biodiversity, pushing the species closer to extinction. In regions like Assam and Bangladesh, palm oil is a major driver of habitat fragmentation and degradation, especially in forest corridors that once connected populations.

Timber deforestation

Widespread illegal logging, often fuelled by demand for timber and firewood, is rapidly eroding the capped langur’s habitat. Fruiting and lodging trees that are vital to their survival are cut down, leaving forests patchy and disconnected. As their home ranges shrink, capped langur groups are forced into smaller fragments, increasing their vulnerability to predators, food shortages, and inbreeding. In some areas, this pressure has led to local extinctions or the collapse of entire populations.

Slash-and-burn agriculture

Slash-and-burn agriculture destroys habitat for capped langurs and often brings them into closer contact with human settlements, increasing conflict and risk of hunting or roadkill. Forest recovery from this can take decades—time the capped langur simply doesn’t have.

Hunting and the illegal pet trade

Capped langurs are hunted for their meat, pelts, and for sale in the illegal pet trade. In many tribal and rural areas of Assam, Arunachal Pradesh, and Manipur, they are still targeted despite legal protections. Their pelts are used to make traditional knife sheaths, and infants are often captured after killing their mothers, then sold as pets. This exploitation causes severe suffering and has a devastating impact on group structures, leading to long-term population decline.

Roads cut into rainforests for mines and tea plantations

As forests are cut into smaller patches for roads, mining, tea plantations, and settlements, capped langur populations become increasingly isolated. Small, disconnected populations face higher risks of inbreeding, loss of genetic diversity, and eventual extinction. In some regions, such as Tinsukia and Sonitpur, populations have already disappeared due to this fragmentation. The collapse of corridors also disrupts daily movement, feeding patterns, and access to mates—placing enormous stress on surviving individuals.

Hybridisation with other species

Due to the rapid degradation of natural habitats, capped langurs are increasingly forming mixed-species groups with the closely related Phayre’s langur (Trachypithecus phayrei). Recent studies in northeast Bangladesh confirm genetically that hybridisation is occurring, which could result in the eventual cyto-nuclear extinction of the capped langur lineage. Although hybridisation can happen naturally, in this case it is being driven by human-induced fragmentation, forcing species into overlapping territories with fewer options for mates. This phenomenon is both a symptom and a driver of their decline, complicating conservation efforts.

Mining, infrastructure, and political conflict

Open-cast coal mining, limestone extraction, and petroleum exploration have all contributed to the destruction of capped langur habitat across Assam and Nagaland. Infrastructure projects, such as highways and border fences, not only destroy habitat directly but also block animal movements and isolate populations. In border regions, armed conflict and territorial skirmishes have already extirpated capped langurs from several reserves, such as the Nambhur and Rengma forests. Weak law enforcement allows habitat destruction to continue unchecked in many regions.

Geographic Range

Capped langurs are found in northeastern India (Arunachal Pradesh, Assam, Meghalaya, Nagaland, Manipur, Mizoram, and Tripura), Bhutan, northwestern Myanmar, and northeastern and central Bangladesh. They occur at elevations from 10 to 3,000 metres across hill forests, riverine reserves, and protected areas. However, their range is now severely fragmented by human development, with some populations disappearing from former strongholds due to mining, conflict, and agricultural encroachment.

Diet

Primarily folivorous, the capped langur’s diet includes mature and young leaves, petioles, seeds, flowers, bamboo shoots, bark, and occasionally caterpillars. They forage on more than 43 plant species, with favourites including banyan (Ficus benghalensis), sacred fig (Ficus religiosa), Terminalia bellerica, and Mallotus philippensis. Seasonal availability influences their feeding patterns, but they consistently prefer fruiting and flowering trees.

Mating and Reproduction

Breeding usually occurs in the dry season, with birthing concentrated between late December and May. The gestation period lasts about 200 days, and the interbirth interval is approximately two years. Only parous females participate in allomothering, allowing new mothers time to forage and recover, a behaviour rare among langurs and considered a form of altruism.

FAQs

How many capped langurs are left in the wild?

Exact numbers are uncertain, but estimates suggest the population in Assam has declined from 39,000 in 1989 to approximately 18,600 between 2008 and 2014 (Choudhury, 2014). This halving reflects habitat loss and increasing fragmentation, particularly in Upper Assam and the Barak Valley.

What is the average lifespan of a capped langur?

While data is limited, langurs of this genus generally live 20–25 years in the wild. Captive lifespans may extend slightly due to the absence of predators and constant food supply, though such conditions often lead to stress.

Why are capped langurs under threat?

Their decline is due to relentless deforestation, palm oil and monoculture plantations, illegal logging, and road-building. Slash-and-burn agriculture and mining also play a major role. Capped langurs are hunted in some regions for meat, pelts, and as pets, particularly in Assam, Arunachal Pradesh, and Nagaland.

Do capped langurs make good pets?

Absolutely not. Capped langurs are intelligent, social beings that rely on complex forest habitats and close-knit family groups. Removing them from the wild fuels extinction and causes immense trauma. Many die during illegal capture and transport. Keeping them as pets is a selfish act that destroys lives. If you care about capped langurs, never support the exotic pet trade!

What are the major conservation challenges for capped langurs?

The biggest issues are hybridisation with other primate species, habitat fragmentation, palm oil expansion, and human-wildlife conflict. The 2018 study in Satchari National Park found that local attitudes toward conservation vary by occupation, education, and gender, which means education and outreach are crucial. A big challenge is the rise in hybridisation with sympatric Phayre’s langurs, driven by habitat degradation—this poses long-term genetic risks (Ahmed et al., 2024).

Take Action!

Capped langurs are vanishing before our eyes, driven to the brink by out-of-control palm oil expansion, deforestation, and development. You can help save them.

Refuse to buy products made with palm oil. Support indigenous-led conservation in northeast India and the Eastern Himalayas. Demand governments halt the destruction of old-growth forests and restore wildlife corridors. Spread awareness and challenge the illegal wildlife trade. #BoycottPalmOil #Boycott4Wildlife #Vegan #BoycottMeat

Support the Capped Langur by going vegan and boycotting palm oil in the supermarket, it’s the #Boycott4Wildlife

Support the conservation of this species

This animal has no protections in place. Read about other forgotten species here. Create art to support this forgotten animal or raise awareness about them by sharing this post and using the #Boycottpalmoil #Boycott4Wildlife hashtags on social media. Also you can boycott palm oil in the supermarket.

Further Information

Ahmed, T., Hasan, S., Nath, S., Biswas, S., et al. (2024). Mixed-Species Groups and Genetically Confirmed Hybridization Between Sympatric Phayre’s Langur (Trachypithecus phayrei) and Capped Langur (T. pileatus) in Northeast Bangladesh. International Journal of Primatology, 46(1), 210–228. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10764-024-00459-x

Das, J., Chetry, D., Choudhury, A.U., & Bleisch, W. (2020). Trachypithecus pileatus (errata version published in 2021). The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2020: e.T22041A196580469. https://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2020-3.RLTS.T22041A196580469.en

Hasan, M.A.U., & Neha, S.A. (2018). Group size, composition and conservation challenges of capped langur (Trachypithecus pileatus) in Satchari National Park, Bangladesh. Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/339550399

Wikipedia. (n.d.). Capped langur. Retrieved April 6, 2025, from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Capped_langur

How can I help the #Boycott4Wildlife?

Take Action in Five Ways

1. Join the #Boycott4Wildlife on social media and subscribe to stay in the loop: Share posts from this website to your own network on Twitter, Mastadon, Instagram, Facebook and Youtube using the hashtags #Boycottpalmoil #Boycott4Wildlife.

Enter your email address

Sign Up

Join 3,173 other subscribers2. Contribute stories: Academics, conservationists, scientists, indigenous rights advocates and animal rights advocates working to expose the corruption of the palm oil industry or to save animals can contribute stories to the website.

Wildlife Artist Juanchi Pérez

Mel Lumby: Dedicated Devotee to Borneo’s Living Beings

Anthropologist and Author Dr Sophie Chao

Health Physician Dr Evan Allen

The World’s Most Loved Cup: A Social, Ethical & Environmental History of Coffee by Aviary Doert

How do we stop the world’s ecosystems from going into a death spiral? A #SteadyState Economy

3. Supermarket sleuthing: Next time you’re in the supermarket, take photos of products containing palm oil. Share these to social media along with the hashtags to call out the greenwashing and ecocide of the brands who use palm oil. You can also take photos of palm oil free products and congratulate brands when they go palm oil free.

https://twitter.com/CuriousApe4/status/1526136783557529600?s=20

https://twitter.com/PhillDixon1/status/1749010345555788144?s=20

https://twitter.com/mugabe139/status/1678027567977078784?s=20

4. Take to the streets: Get in touch with Palm Oil Detectives to find out more.